3.2 Being aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer

It is often claimed that the essence of a systems approach is that of seeing the world in a special way. This immediately prompts the question of what is meant by the phrase ‘seeing the world’. Because we live so intimately with the world of objects, categories and people and phenomena, we tend to think our own way of seeing the world is the only way, or even of thinking, ‘Well that is my view because the world is like that’. Actually, your view is special in several separate ways.

(a) If your vision is not impaired, you see your surroundings using only light of wavelengths between 380 nm and 780 nm (nanometers or 1 × 10−9 m). Bees, for example, see flowers using wavelengths less than 380 nm. You have quite a small visual window on the world.

(b) Research on colour perception in the 1960s showed that colour was not something that is fixed in the world, but is a property of our own unique histories. This led one of the researchers involved to change the question he was concerned with from ‘how do I see colour’? to ‘what happens in me when I say that I see such a colour?’

(c) With normal hearing you hear frequencies of sound between 20 Hz and 20 000 Hz (Hertz). Bats use sound waves of higher frequency than 20 kHz, which we cannot hear.

(d) Your ability to detect odours is vastly inferior to a dog's. A dog's ‘smell world’ is vastly richer than its visual world.

(e) The language you have learned steers you into categorising your world in ways you are largely unaware of, just as a fish is unaware of the water it is immersed in throughout its life. Sometimes it is possible to become aware of this when speaking another language – when immersed in the other language the experience is sometimes like being a different person.

(f) Your physiological state and the dynamic relationship of this with your emotional state also affect how you experience the world. This ranges from aspects of the functioning of your nervous system and its role in cognition, to hormonal events such as menstruation, and the release of natural endorphins during exercise.

(g) The culture of the society in which you have developed has determined what you see as well as how you can respond in any flow of relationships. Your culture determines what is implicit in your perceptions and emotions. So the ways you see manners, relationships and behaviours is dependent in turn on how people around you see and act.

(h) A special subset of the last point is the particular explanations we accept for things we experience. The ‘theoretical windows’ through which we interpret and act are always with us regardless of whether we are aware of them or not. Figure 26 provides a metaphorical account of this phenomenon. The theory or explanation you accept will determine what you see and thus the meaning you will give to an experience. Think here, for example, of the fundamentally different cosmology, the set of explanations for the origin and evolution of the universe, developed by the Mayan civilisation in South America that was entirely coherent but so different to Western cosmology. This is sometimes described as the theory dependency of facts.

Activity 36

Checking out your own capacities as an observer.

(This should take no more than 10 minutes.) Even now, your mind set – the way you see things – can be easily influenced. To see how this statement is true follow the instructions carefully.

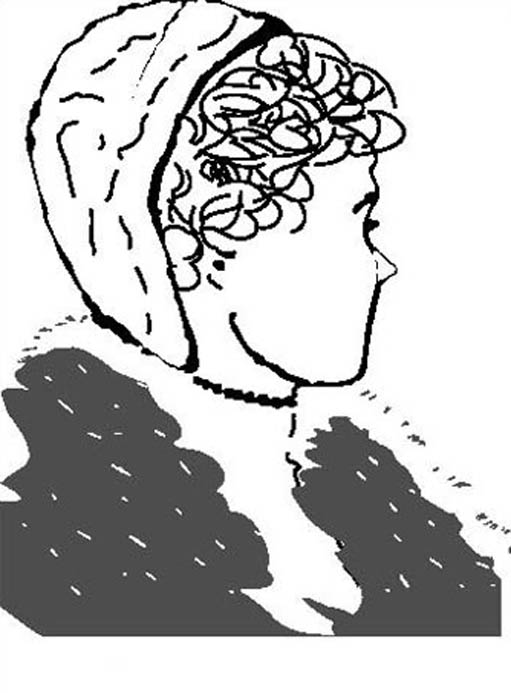

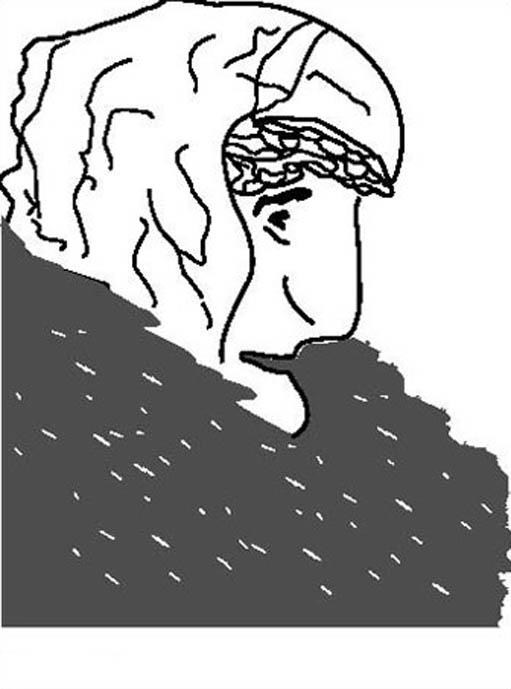

If your last name begins with a letter between A to M, look carefully at Figure 27. Then look carefully at Figure 29.

If your last name begins with a letter between N to Z, look carefully at Figure 28. Then look carefully at Figure 29.

If you are an A-to-M, you probably saw the young woman, and if you are an N-to-Z, you probably saw the old woman. Tests of these pictures, done with groups of students, show that prior influence is always powerful. This activity raises two important questions.

What is experience? In this example some people experienced a young woman whilst others experienced an old woman yet both looked at the same image. This leads me to claim that experience arises by making a distinction – if you are unable to distinguish a young woman then you have no experience of one!

Is it possible to decide on which interpretation, the young woman, the old woman or merely the ink on the paper, is correct? In other words do we reject those people who see only an old woman as being ‘wrong’?

On the basis of doing Activity 36 try the next activity. Spend no more than about 10 minutes on it.

Activity 37

When you talk about experience what do you mean?

Describe what was, for you, a new experience.

For me the following story was helpful in making sense of what I mean by experience. I had the good fortune to do a consultancy in South Africa just after the first multi-racial elections. It was a time of goodwill and enthusiasm and general optimism. An incident happened towards the end of a flight from Johannesburg to East London in the new province of the Eastern Cape.

As the plane taxied up the tarmac towards the terminal, I experienced my South African colleague, in the seat next to me, as becoming agitated and tense. Looking out the window, as he was, I could not distinguish anything that I could see as the cause of his distress. When I enquired, he pointed to some seemingly innocuous cement pillars, which he explained were the remains of gun emplacements left over from the state of emergency in the apartheid era. Because of his history, which was different to mine, he had seen what I could not see – that is, his observation consisted of distinctions that I had not made. Furthermore, the distinctions my colleague made altered his mental, emotional and physiological state – they altered his being. My colleague made distinctions I was unable to make and thus he experienced something I did not.

The act of making a distinction is quite basic to what it is to be human. When we make a distinction we split the world into two parts: this and that. We separate the thing distinguished from its background. We do that when we distinguish a system from its environment. (Remember, using the word system is actually shorthand for specifying a system in relation to an environment.) In process terms, this is the same as drawing a circle on a sheet of paper. When the circle is closed, three different elements are brought forth at the same time: an inside, an outside and a border (in systems terminology, a boundary). In daily life we have developed all sorts of perceptual shortcuts that cause us to forget this is what we do – we live, most of the time, with our focus on one of these three elements: the inside, the outside, or the border. Biologically, we cannot focus on both sides of a distinction at the same time. Heinz von Foerster (1984) observed that the descriptions we make say more about ourselves than about the world we are describing.

While the old woman–young woman example is now well known, the implications that flow from it are not. The activity, and the points listed prior to that demonstrate that in the experience we cannot distinguish between perception and illusion and that ‘we do not see that [which] we do not see’ (Maturana and Varela, 1987). It is ironic that we pay money to go and see illusionists, and marvel at their artistry, yet remain unaware that illusion is also part of daily life. For systems practice this idea is challenging in a number of ways:

(a) It draws my attention to what is involved in the process of modelling, of which diagramming is a subset. It raises the question of whether we model some part of the world or model our models of some part of the world.

(b) It challenges the certainty of some practitioners who claim they are objective or they are right, and because of this, affects the way they practise.

(c) It reminds me that my perspective is always partial and a product of my cognitive history (I would include emotions as part of a cognitive history). Thus, when forming a system of interest, the question of ‘perspective, who's perspective?’ is crucial.

(d) It reminds me to be aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer as I juggle the B ball in my practice.

The properties and role of the observer have been largely ignored in science and everyday culture despite Werner Heisenberg's finding in 1927 that the act of observing a phenomenon is an intervention that alters the phenomenon in ways that cannot be inferred from the results of the observation. This is the essence of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, which limits the determinability of elementary events (von Foerster, 1994). The story of how the observer came into focus is an interesting one in the history of Systems and its associated field of cybernetics. Lloyd Fell and David Russell (2000) describe it in the box below; its lineage can be seen in Figure 24.

Being aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer enhances our repertoire of behavioural responses. Because we are able to communicate with one another, and because we live within cultures we can take shortcuts: it makes sense sometimes to act as if we are independent of the world around us. Sometimes it also makes sense to act as if systems existed in the world and as if we could be objective. But remember, the two small words as and if are important in the context of our behaviour when we attempt to manage. From the perspective developed in this section, it is always a shortcut when we leave them out.

Box 1 How the observer has come into focus

Cybernetics, although often applied to the control of machines, has long been one of the foundations of thought about human communication, its central notion being circularity. Cybernetics ‘arises when effectors, say a motor, an engine, our muscles, etc., are connected to a sensory organ which, in turn, acts with its signals upon the effectors. It is this circular organization which sets cybernetic systems apart from others that are not so organized’ (von Foerster, 1992). In first-order cybernetics it was the idea of feedback control which mainly occupied the practitioners, but in time the question ‘what controls the controller’ returned to view (Glanville 1995a,b) and the property of circularity became the focus of attention once again.

Second-order cybernetics is a theory of the observer rather than what is being observed. Heinz von Foerster's phrase, ‘the cybernetics of cybernetics’ was apparently first used by him in the early 1960s as the title of Margaret Mead's opening speech at the first meeting of the American Cybernetics Society when she had not provided written notes for the Proceedings. [The understandings which have arisen from second-order cybernetics …] requires a loosening of our grip on the supposedly certain knowledge that is acquired objectively, about a reality existing independently of us, and a willingness to consider the constructivist idea (see Mahoney, 1988) that we each construct our own version of reality in the course of our living together. The virtue of objectivity was that the properties of the observer should be separate from the description of what is being observed. This led to what von Foerster (1992) called the Pontius Pilate attitude of abrogating responsibility because the observer is an innocent bystander who can claim he or she had no choice. The alternative attitude, which seems to be less popular today, is to own a personal preference for one among various alternatives.

(Fell and Russell, 2000)