4.6 Appreciating some implications for practice

I think for most people, the CSA case study would be experienced as a complex situation. If so this would be a good example of perceived complexity. Remember though, if you engaged with it as if it were a difficulty, just as the government minister did in Activity 42, you would not describe the situation as one of perceived complexity. I could not call it a complex system unless I had tried to make sense of it using systems thinking and found, or formulated, a system of interest within it. This means I would have to have a stake in the issue – an interest. In systems terminology, I would need a purpose for engaging with the ‘real world’ situation. When I do not have such a purpose in mind, I am using the word system in its everyday sense rather than in its technical, systems practice, sense.

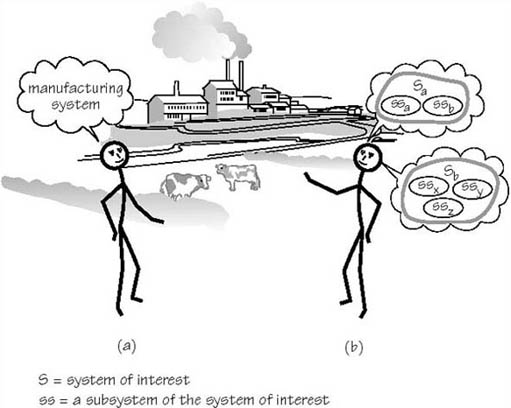

The fundamental choice that faces both systems theorists and complexity theorists is choosing to see system or complexity either:

(a) as something that exists as a property of some thing or situation; and that, therefore, can be discovered, measured and possibly modelled, manipulated, maintained or predicted; or

(b) as something we construct, design, or experience in relationship to some thing, event, situation, or issue because of the distinctions – or theories – we embody.

There are profound differences between these two options, as I have tried to depict in Figure 37.

These epistemological choices depicted in Figure 37 determine the nature of the engagement – the E ball – of a systems practitioner with a ‘real world’ situation. The first choice says a lot about the nature of the thing or situation but says little about the practitioner concerned with the thing or situation. This is the situation where technical rigour, of the type described by Schön in his quote in Section 4.3, informs practice. Schön describes this as technical rationality in which there is a radical separation of research – and what is regarded within this epistemology as legitimate knowledge – and practice.

The latter position however, has a lot to say about the practitioner and about what they know and are able to do, as well as about their relationship to the thing or event they experience. In this situation the systems practitioner is engaged with the complex situation. He or she must construct or design alone, or with other stakeholders, the system of interest and choose to see the situation as complex or simple, mess or difficulty.

Taking responsibility for the choice you make about these two distinctions is an act of being epistemologically aware. The aware systems practitioner recognises that a system of interest is an epistemological device, a way of creating new ways of knowing. (I return to this in Part 3, Section 5.) The unit is designed to help you develop your skills in being aware as part of your systems practice. At this stage, all you need to do is to note your reaction to my claim about being epistemologically aware. Do you recognise something of what I mean or does it seem quite meaningless and unnecessary? I anticipate both responses, so don't worry if you fall into the latter category. I have already introduced the basis for my position in this section and I intend to clarify it further in Section 5.

Let me emphasise here, making a choice of one epistemological position or another in a given context is not an act of discarding or deciding against the other position – it is an act of being aware of the choice you made. Both positions offer rich explanations of phenomena in different contexts.

In Part 2 you were moving towards formulating systems of interest by drawing a rich picture; by drawing systems maps and making the necessary boundary judgements; by drawing influence diagrams, and multiple-cause diagrams to look at the dynamics of influence and causation; and by drawing control diagrams to look at the idea of inputs and outputs and transformation processes. You have in fact begun to juggle the E ball yourself. It will require a further judgement on your part, against some criteria, as to whether you recognised your system of interest as a complex system or as a simple system. In doing this you could choose criteria from any of the perspectives on complexity described in Appendix C. In this unit we are not greatly concerned with ascribing the adjectives simple and complex to a system, except to the extent that your choice of adjective reflects your capacity to manage complexity. Reflecting on some of the problematic practices in the field of biological science, Stephen Rose (1997) suggests it is due to the ‘cultural difficulty we have in perceiving a world of fields and processes rather than objects and properties’. The same phenomenon seems common in other forms of practice.

The next activity should take you about 10 minutes.

Activity 46

Complete and review the additions to the diagram you started in Activity 40.

Add any new understandings, or development of old understandings about the meaning of complexity.

Write a few paragraphs of notes about what has changed and how and, if possible, what triggered the new understandings.

Part 3, Section 4 may have presented you with more questions than answers. If this is true for you, don't worry, that was the intention. As I outlined in Appendix C, there is no agreed meaning for complexity. For the main part, in this unit we shall be referring to perceived complexity unless the author suggests otherwise. The ambiguities implicit in facing questions where the only honest answer is, ‘I don't know’, need not be troubling, once you get used to them. Living with these ambiguities is actually a powerful way of learning to manage complexity and being a systems practitioner. It might be argued that a lack of certainty can be an advantage in that it provides a space to think about, or reflect on, how your practice might be contextualised to the situation. Contextualisation, the C ball, is the subject of the next section.

SAQ 12

For each of the following situations, decide whether it is best considered as a mess or a difficulty.

(a) The group that runs a local orchestra continually argues about whether they should stick with popular classics or venture into more difficult and less popular pieces.

(b) Joan wants to send a computer file to Ray, but they use incompatible types of computer software.

(c) Although the company started as a software business, it now received most of its revenue from consultancy work. At a board meeting the issue about whether to continue developing and selling software was raised. This is partly due to the increasing cost of programmers, but also because software sales were declining. However, the software is used in all the consultancy work, and some of the projects involve extending the software to new areas.

(d) Jack is buying a new car and his most important criterion for choice is fuel economy.

(e) An environment agency has legislative responsibility for controlling pollution but the fines imposed on polluters are minimal.

Now decide what might be gained by considering each situation as if it were a simple or complex system or as a complex adaptive system.

Answer

My answer to this SAQ comes from my own experience, which may lead me to choose different answers to yours, which are based on your experience. Having experienced how much effort is required to work effectively in groups, I regard (a) as a mess. I do so because hidden behind what appears to be a simple choice of musical direction may lie conflict, emotion and a clash of values, which I could recognise as a system of problems. I view (b) as a difficulty based on my belief that a technical and unambiguous solution exists for the problem. If I were to move my boundary around this situation to encompass the generic issue of software platform compatibility, it might better be regarded as a mess. The issue of whether to maintain both PCs and Macs is a complex and emotive issue in the OU for example. I regard (c) as a mess because there are likely to be different perspectives on what constitutes a problem or opportunity. As given, I would regard (d) as a difficulty and (e) as a mess.

In some circumstances it might be helpful to consider (e) as if it were a complex system. I say this because I imagine it involves a large organisation – the agency – and large social institutions – Parliament and the law. On the criterion of centralised decision making (see Table 3) I would choose to regard all the other situations as simple systems, but in doing so I feel I have gained nothing helpful for my systems practice.