16 Part 3: 6 Managing complexity

6.1 Perspectives on managing

My focus in this section is on the M ball being juggled by a systems practitioner. My purpose is to enable you to appreciate the diversity of activities that might constitute managing. More specifically, I am concerned with the type of managing a systems practitioner might undertake. When you began Part 3, Section 4, I asked you to complete an activity (Activity 40) in which you used a spray diagram to record the different meanings you associated with the phrase managing complexity. I wonder: did your answer focus on the managing or the complexity or both?

Before going on, I want you to engage in a short ideas generating session to develop a list of all the verbs you associate with the word managing. Use Activity 30 as a starting point to trigger your thinking. Spend about five minutes on generating the ideas for the list and another five minutes on the sorting.

Activity 50

Generate a list of the verbs you associate with managing.

Generate and list all the verbs you associate with the word managing.

Sort through them and develop some categories that help you to group and make sense of your list.

Some of the verbs we (I did this with a colleague) thought of were understanding, surviving, seeing, visioning, allocating, optimising, communicating, commanding, controlling, helping, defending, leading, supporting, backing, enabling, coping, informing, modelling, facilitating, empowering, encouraging, delegating. I identified three categories that helped me make sense of the list. These were (a) getting by; (b) getting on top of; and (c) creating space for. I make no claim that this list is definitive; my categories are ones that I found useful at the time. Undoubtedly your list and categories will be different. For example, the functions – the verbs – in the Act that led to the establishment of the Child Support Agency were process, trace, investigate, assess, collect and enforce. So these were the activities, presumably that had to be managed.

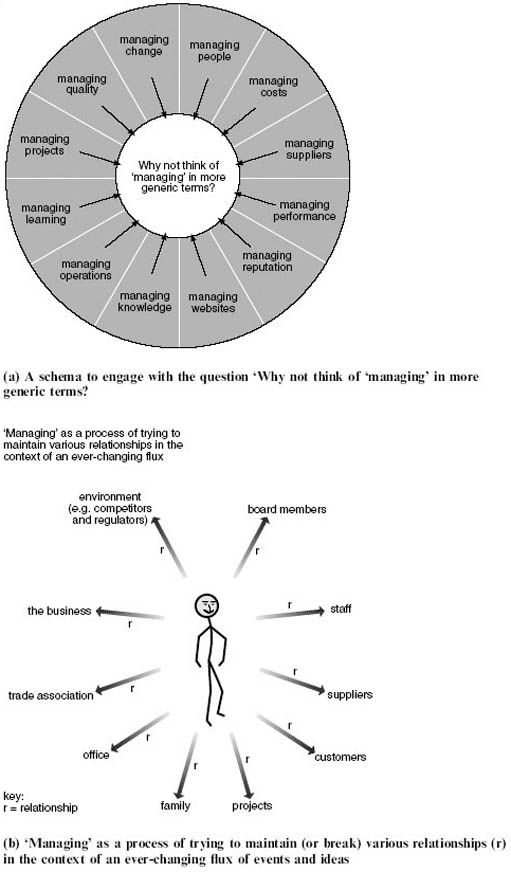

My concern in this section is with managing in all its manifestations and how these are embodied in a particular manager. I am not concerned with management. When I think of a manager, I think of anyone in any context who is engaged in taking purposeful action. That includes you and me. Winter (2002) asks the question ‘Why not think of “managing” in more generic terms?’ and illustrates this in the form of Figure 45a. Later he casts the act of managing in terms of a process of relationship maintaining (Figure 45b)

The frequency with which we perceive mess or complexity is high, so it seems to make sense to envisage a role for the systems practitioner as someone engaged in managing. I do not have a new professional management elite in mind – though this could also exist – but more a citizenry enabled with systems thinking and practice. I am aware, for example, of the millions of people around the world who now engage in local and family history research. It seems many live with a passion for explaining who they are and where they have come from. I would describe all of these people as researchers. So, for me researchers are not just confined to laboratories and universities.

Research in this sense is willed action, done for a purpose, though the purpose may not be clear and involve a mix of emotion and intellect. At this stage of the course, I am going to suggest that taking purposeful action about an issue or situation experienced as complex is at the core of managing complexity.

The enactment of systems thinking in any particular systems approach by a systems practitioner is also an enactment of the experiential learning cycle (Figures 32 and 39). The history of Kolb's articulation of this cycle can be traced back to the work of Kurt Lewin shortly after the Second World War. Lewin is generally recognised as the originator of the notion of action research. When we connect with this history, it is possible to recognise the experiential learning model as a model for action research as well.

The idea of the systems practitioner as action researcher will be increasingly developed as the course goes on. (It is also described by Checkland in Appendix D). These ideas also provide a conceptual framework to imagine what the life-long learner might be, this idealised person that has become so popular in recent discourse.

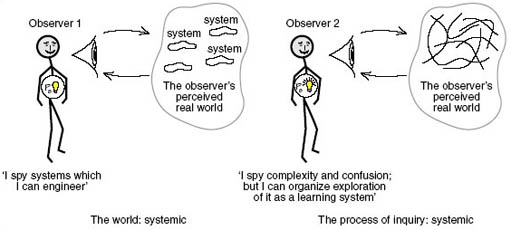

An aware practitioner-as-manager, having chosen to take a systems approach, will always face choices. One of the main choices is whether to formulate a system of interest as part of a process of understanding a situation experienced as complex, a systemic process of inquiry, or to see systems as operational parts of a taken for granted ‘real world’. This choice is depicted in Figure 46.

The systemic approach involves using systems thinking to construct an epistemological device as part of an inquiry process through which we can generate fresh and insightful explanations and which trigger new ways of taking purposeful action in the world.

Based on my experience, the systematic route is inherently conservative and likely to result in first-order change: doing the same thing more effectively or optimally (see Ison and Russell, 2000). This has its place. The systemic route opens up the possibility of second-order change, change that changes the ‘whole system’. An example here is encompassed by asking the following: What is the system to which the Child Support Agency is the answer (the how)? The systemic exploration of this question enables new systems of interest to be formulated, which can be used by those in the situation to arrive at new understandings on which to base their actions.

The same choices face complexity theorists or thinkers (see Appendix C). They may choose to see complexity existing in the world, or they may see complexity thinking as providing the means to formulate an epistemological device that is capable of generating new explanations about the world, as opposed to descriptions of it.