1 What is Ovid’s Metamorphoses?

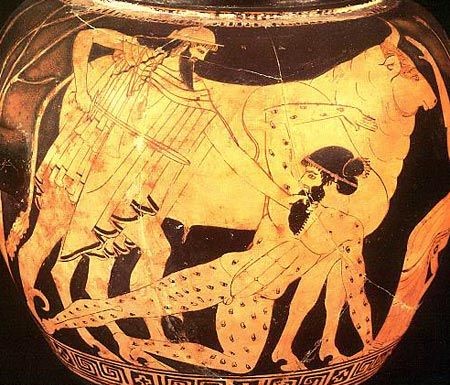

It is difficult to sum up Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It is an epic poem, but one that disobeys almost every expectation that a Roman audience would have had about epic. It does not have a central hero, it takes the form of multiple stories told over 15 books, and frequently shifts in tone from comic to tragic and from irreverent satire to political statement. The poem was difficult to categorise even for its ancient readers. The Roman writer Quintilian (who was born in what is now Spain in the first century CE) described its author as ‘naughty even in his epic verse, and too in love with his own brilliance’! Ovid was living in a time of huge change (43 BCE–17/18 CE). Rome was transforming from a republic into a new system – an empire – under the control of one man, the first Roman emperor, Augustus. Against this backdrop, it makes sense that the main thread of the Metamorphoses should not be the story of a brave hero or a great queen or the foundation of a city, but transformation itself. The poem is full of stories of women who are transformed into trees, men who become deer, cows with human feelings and humans who are turned into gods.

Study note: a note on dates

You will notice that this course uses the abbreviations ‘BCE’ and ‘CE’ when dating events, texts and objects. These abbreviations stand for ‘Before the Common Era’ and ‘Common Era’. You may be familiar with an alternative method of referring to dates as ‘BC’ (‘before Christ’) and ‘AD’ (Anno Domini, Latin for ‘in the year of our Lord’), and you may find that the authors of other things you read on the topics discussed here use BC and AD instead of BCE and CE. Remember that BCE years count backwards – therefore the eighth century BCE is earlier than the seventh century BCE.

At the beginning of his poem, Ovid himself tells us what the poem will be about. Let’s read it now, and investigate what insights it offers into the Metamorphoses.

Activity 1 Beginnings

Read the opening lines of the Metamorphoses reproduced below, translated by Stephanie McCarter. These lines are puzzling, but important. They are the readers’ first encounter with the poem, and help to set up their expectations about what will follow.

Make some notes in the text box below.

My spirit moves me to tell of shapes transformed

into new bodies. Gods, inspire my work

(for you’ve transformed it too) and from creation

to my own time, spin out unceasing song.

A note on book and line numbering:

You may have noticed that McCarter’s translation of the Metamorphoses (which you will sometimes see abbreviated to Met.) is divided into books from 1 to 15, and into lines – here you are reading lines 1–4. Conventionally, when researchers refer to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they tell their readers how to find the passage they are referring to by way of a numbering system which gives the number of the book followed by a full stop, then the number of the lines. For instance, in this activity, you are asked to read the first four lines of book 1, which is referenced as ‘1.1–4’. The line numbers that are given in a translation like McCarter’s correspond relatively closely to the line numbers of the Latin text, but not exactly. This is because certain expressions in Latin are longer or shorter than they are in English. You do not need to refer to the Latin text at any point in this course.

Now re-read these opening lines. As you read this time, choose two phrases that tell you something about the themes of Ovid’s poem. Note them down and briefly explain what expectations you think they offer to readers about what sort of a poem the Metamorphoses is going to be.

Discussion

There are lots of different phrases that you might have focused on here. Your attention might immediately have been drawn to the phrase ‘shapes transformed into new bodies’, which announces that the poem will be about the idea of transformation and change. You may have also noticed the importance of the gods and their inspiration to Ovid, and you may have noted down the phrase ‘Gods, inspire my work’, which highlights the enormous role that the gods will play in the stories Ovid tells.

You may have also picked out the phrase ‘spin out unceasing song’. Here, Ovid is using the image of spinning thread (i.e. transforming it from natural fibres – like a woollen fleece for example – into yarn) as a metaphor for writing poetry. The word ‘unceasing’ (which just means ‘without stopping’) gives the impression of one long continuous thread that is spun. This phrase made it seem likely to me that the Metamorphoses would be a poem in which Ovid’s own voice as a poet plays an important role because of the reference to ‘my own time’. It also suggested a concern with larger themes like fate and the long span of history.

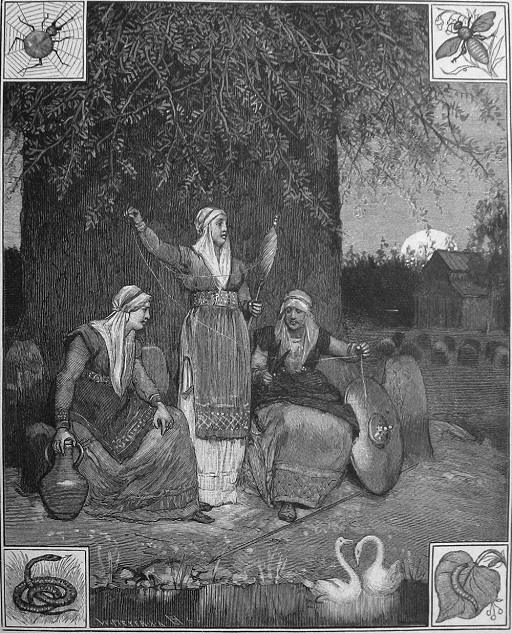

The two phrases – ‘shapes transformed into new bodies’ and ‘spin out unceasing song’ – which were picked out in the discussion give us important clues about Ovid’s poem – and there may be other clues in the phrases you picked out in Activity 1, too. Like many ancient poets, Ovid believed the poem to have come to him from a ‘spirit’ – sometimes called a Muse by other poets. The metaphor of the poem being spun out like a thread might seem strange to modern readers, but it was a frequently used image in the ancient world. It is a reference to the idea of the Fates (known as Moirai in Greek and Parcae in Latin), three sisters who in mythology were said to spin out the destiny of mortals as if they were spinning thread on a wheel.

In your answer to Activity 1, you might also have remarked on the long time span of the poem. Ovid tells his readers that the poem will tell of transformations ‘from creation / to my own time’. In fact, creation is the very first act of transformation that takes place in the poem. To delve a bit deeper into the Metamorphoses and the big questions it asks, you’ll begin where Ovid begins: with the creation of the world.