4.2 Defining the human

When a human character is transformed into a non-human form in myth, readers have to think about where the boundary line is drawn between humans and non-humans. Being human is only a temporary condition in Ovid’s poem. It is not something static, that all humans can be assured of until the end of their lives. This invites Ovid’s readers to ask an enormous question: what makes a human a human? Where does the human stop and the animal, or plant or god begin?

In one sense, we can all answer this question. We all are human, and so we know from experience how to identify human beings as a category. But it is much more difficult to produce a definition of a human. Throughout the history of the modern world, certain humans have been denied recognition as humans. This is the case, for instance, for African people who were enslaved in the Atlantic (and other) slave trades, and who were not considered to be fully human by their enslavers. History makes it obvious how contested this definition of the word ‘human’ can be – and it also shows how much cruelty and violence can result from excluding certain humans from the category ‘human’.

Even in the contemporary world, some people are still fighting to be fully recognised as humans. These images from protest movements show people using declarations like ‘We are humans’ to fight for the rights of refugees, queer people, Black people and other people of colour.

Activity 8 Define a human

Set a timer for five minutes, and write down a single sentence definition of a human being. Try to write your definition so that it will only include human beings, and not animals, artificial intelligence or anything else that might share some characteristics with humans.

Discussion

Here is an example answer:

I did not find a definition that I found completely satisfactory, but I learned something important in the process. I started off trying to produce a definition of the human on the basis of ability. By this, I mean that I tried to single out what humans can do that animals (or robots) cannot do. I tried ‘A human is an animal that can speak.’ first of all, but this did not hold up to scrutiny. Computers or robots, after all, can speak (though it could be argued that they rely on a human programmer to do so). More importantly, though, this definition of the human risked being discriminatory. Babies cannot speak, but they are no less human for not being able to do so. And many disabled humans would be excluded from the category of the human if the human were defined on the basis of a particular ability – so such a definition would be ableist. I concluded that how we define what a human is changing all the time and that humans are perhaps not as special or separable from other living things as I had previously thought! In other words, I concluded that I no longer thought human exceptionalism to be a particularly useful way of thinking about what it means to be human.

I hope you managed to come up with a definition. Or, if you were like me and struggled to answer this question, that you found the struggle useful!

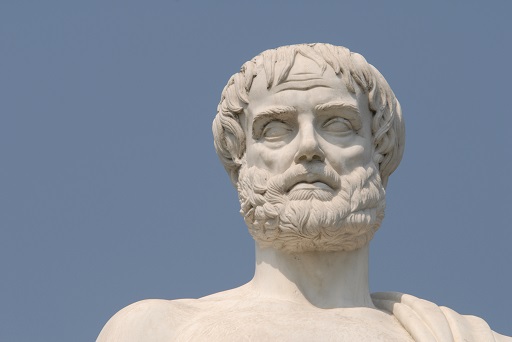

The question ‘what makes a human human?’ in some ways feels like a thoroughly modern question. You may have encountered this question in the context of the development of technology, like artificial intelligence, which sometimes seems to threaten to be able to do tasks that had previously been thought to be specific to human beings. But writers in the ancient world were also concerned with this question. In ancient Greece, the philosopher Aristotle (who lived in the fourth century BCE) tried to come up with a solution. In the next activity, you will consider Aristotle’s definition and explore how it compares with the single sentence definition that you worked on in Activity 8.

Activity 9 An ancient definition

Read this short extract from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. This excerpt is short, but it is philosophically quite complex. You may like to read it through two or three times to make sure that you understand the stages of Aristotle’s argument. Comparing it with your own definition (from Activity 8), answer the following two questions:

- What is it that distinguishes humans from other forms of life, according to Aristotle?

- How convincing do you find Aristotle’s argument? Can you think of any arguments against his conclusion?

To provide some context, at this point in the text, Aristotle is trying to discover how it is that humans can be most ethical. This requires him to identify what it is that is specific to humans. If he can find out what it is that humans alone are able to do (their function), he suggests, then he will be able to argue that doing this to the best of their ability is what it means to be ethical. For example, if rational thought is the function of humans, then their most ethical behaviour is thinking rationally as well as they can.

The definition of human function that Aristotle gives is as follows:

What then can this function be? The simple fact of being alive is something shared with plants, but we are looking for that which makes humans special. We must therefore set aside nutrition and growth, those activities that are simply for the purpose of living. Next, we could consider activities like perceiving and feeling, but these things too are shared with horses, oxen and most other animals. What remains, then, is the use of rational thought.

Discussion

Here is a sample answer for each of the two questions:

- For Aristotle, what distinguishes humans from other forms of life is their capacity for rational thought. This argument is often simplified into the phrase ‘a human is a rational animal’.

- I did not find Aristotle’s argument particularly convincing. I was worried about the idea of assuming that all humans are capable of rational thought. There are many situations that I thought of in which humans are not able to think rationally, and I would not want to argue that the humans in these situations are not human!