5 And then came … monsters

It is very difficult for us in the modern world to give a complete definition of a human being. But in the world of ancient myth, things are even more complicated. As you have discovered, texts like Ovid’s Metamorphoses were full of characters that crossed boundaries between human and animal, plant, god, constellation, river and many other kinds of transformation besides. But there is one category of creatures in ancient myth that make this task of defining a human even more difficult: monsters.

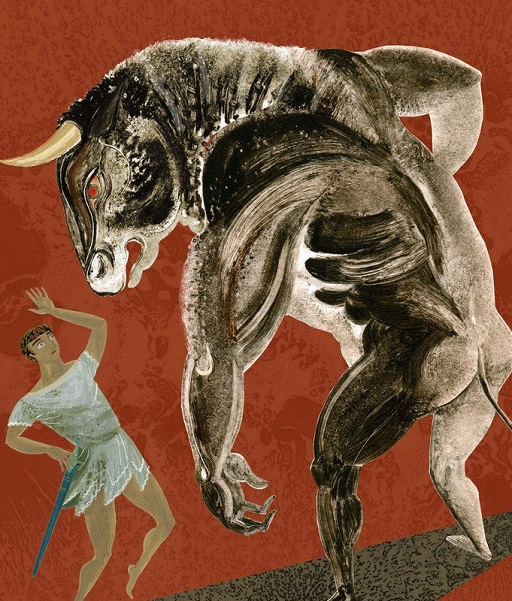

What is a monster? That is a question almost as difficult to answer as ‘what is a human?’! But we can use the examples of monsters that we find in texts like Ovid’s Metamorphoses to help us to try to answer it. Monsters are often marked in myths by having bodies that are part human and part animal. They might have the head of a human and the legs of a bull, for example, or many other combinations. These creatures are known as hybrid creatures, because they are a hybrid of humans and animals. In the next activity you will meet some of these hybrid creatures.

Activity 10 Hybrid creatures

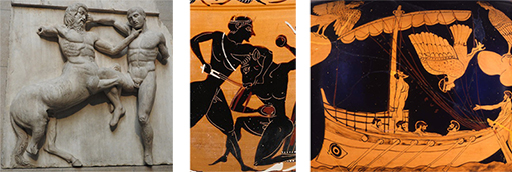

Below are three ancient images of hybrid creatures. In no more than three sentences, describe the hybrid creature in each image. All of these monsters play a role in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but you do not need to be able to identify any of them by name, or know their stories.

Example: In the first image, you might say that the figure on the left is a hybrid creature which has the tail of a horse. You might also point out that his face, torso and hair look human. You may notice, too, that the creature seems to be attacking the other figure in the image.

Discussion

In the second image, the hybrid creature seems to have the body of a human and the head of a bull, with horns. The creature seems to be being attacked by the human standing to the creature’s right.

In the third image there are three hybrid creatures. Each of the three creatures has the body and wings of a large bird, with sharp talons on their feet. Each of the creatures also has the head of a human woman.

Monsters do not only appear in Ovid’s poetry, and monsters from all across ancient literature have had a huge influence on the modern world. The fact that ancient monsters are so commonly returned to has led to many scholars asking the question: why are monsters so popular? What is it that these hybrid creatures do for us? In the next activity you will try to get to grips with this question.

Activity 11 Tracking monsters

Listen to this interview with Liz Gloyn, where she discusses her book Tracking Monsters in Popular Culture (2019) about ancient monsters and the role they play in modern imaginations. In the interview, recorded during the COVID-19 pandemic, she explains why ancient monsters are so popular in the modern world. She offers some answers to the question ‘what do ancient monsters do in the modern world?’. As you listen, write down three possible answers to this question.

Transcript

ANYA LEONARD

In chapter one of your book, you ask, what makes a monster? So I think this is an excellent starting point and perhaps we should begin there. What makes a monster?

LIZ GLOYN

Loads of different things make a monster. It really depends on what you’re thinking about in terms of what the work a monster does culturally. So are we thinking about monsters as things that help-- things that we’re afraid of, obviously. But where does that fear come from?

There’s been some really important work done in the field of monster studies about what precisely the key characteristics of a monster are. So some of those possibilities include being policing factors. So you don’t do something because otherwise the monster will get to you, very familiar one.

Categorisation things. Monsters exist because they break categories. So the Centaur in classical myth is a really good example of this. You have humans. You have animals. And then the monster is the thing that combines the two of them and breaks down the category. So they’re there to help humans articulate what category boundaries are in some interesting ways about the world.

They can be there to reinforce social norms. They can be there to help us articulate fears of the other, whoever the other might be. And what a surprise the other tends to be women, people of colour, people who aren’t like us in terms of religious background, whatever that might be. And that then becomes in its turn because the other has become monsterised-- monsterises the other, and then that sort of legitimates all sorts of unpleasant treatment on the basis of monstering. And sexual orientation, obviously, is sort of a very popular one. But I mean, it’s the social factors that come together to create monsters in some really interesting ways and monsters that are very specific to their cultures. That’s why in the modern era, we find so many types of monster that are really about a fear of not being able to spot the monster in time and a way in which we can’t see the monster at all.

So you have the serial killer. You don’t know the serial killer. It’s a serial killer until it’s too late, and the camera pans into the basement and you get the moment of revelation. You have the very closely related cousin to the serial killer, the terrorist, who is kind of weird because you kind of can spot a terrorist because often they have a different colour skin than everyone else, which obviously is a huge problem with racialising the monster.

But then, again, of course, the terrorist, you also can’t see the terrorist and they slip away. And yeah, so that pattern of racialising is sort of quite interesting because obviously people try and spot terrorists, but you can’t. You misidentify people. So again, the monster always escapes in that sense.

You have people who are-- you have films and horrors where the monster is the big faceless government agency, who looks like all the other government agencies. But when you go into the building, they are in fact engaged in some sort of horrible, I don’t know, organ harvesting or whatever it might be. Those kinds of films very much always in the Bourne conspiracy kind of stuff, that sort of end of things.

You have the virus, which of course, I say that now in the current circumstance. But so many films--

ANYA LEONARD

I know that one very much.

LIZ GLOYN

Yeah, exactly. But so many films in which the virus is the monster, the unseeable, the unprotectable. Of course, what the coronavirus does not do is turn people into zombies, which, of course, is what it does in most of the horror movies. But it’s still that same fear of the invisible.

And then the fourth kind of trope, which we’re seeing more monsters of in the contemporary world is monstrous nature. So everything that’s lovely and beautiful and wonderful. And then Mother Earth bites back and there’s a tsunami, there’s a sword, there’s a giant shark, whatever it might be.

Nature getting its own back on humans who have ignored or overseen or somehow violated the pact with nature, very much kind of the unseen monster in the idle, perhaps might be one way of thinking about it. Those are all very modern fears, and they are very much focused on not being able to spot a monster in time to respond to it, which is a very modern paranoia. Very sort of twentieth and twenty-first century fear of not being able to control stuff in a highly controlled and structured society.

Whereas if you look at classical monsters, how do you spot a classical monster? It’s got three heads. Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Tails. Exactly. They’re very obvious and clear and straightforward. And so when you see classical monsters used in popular culture, they’re kind of really reassuringly retro.

ANYA LEONARD

When we think about Greek mythology and you’re saying about these differences how we're re-examining that and those deviations are showing us something about our society. But as a general question, how does studying ancient monsters and mythology help us today? Like, what can we learn about ancient monsters that will make a difference in our lives now?

LIZ GLOYN

I think the fact that people keep on going back to classical reception and keep on wanting to learn more about these stories and tell them again and what we want to-- where we want to go with these issues. And I think it tells us, I mean, this is a very hackneyed phrase, but I’ll use it anyway. That myth is good to think with.

Myth is a good way of exploring those issues and playing out those tensions and taking those rough bits in our own society and not quite thought experimenting because that isn’t quite what I’m after. But using it as a vehicle through which we express and expand our own understanding of what it means to be human.

Now, obviously, the ancient world is hugely different to ours. It’s a different country. It’s a different time. They are very different. They have different value systems. I don’t want to nod towards a world in which it’s like, well, the Greeks were just like us and therefore because they weren’t. They were not at all like us.

But through looking at the way that they construct and they understand and they think about the world, we then can use that same kind of reflectiveness to look at our own constructions, our own beliefs, our own positions and say, well, does it have to be like this really, or is there something here that we might want to unpick a bit? Does the ancient world help us unpick it? Where can we go with this?

So it’s both about mythology, of course, but also just about antiquity in general. It’s a way of helping us to critically engage with the modern world around us, and start to think through some of those issues about constructions of power, constructions of gender, constructions of race, all that kind of stuff, which, if you are unreflectively living in the moment, TM, look like they’re immutable and they should never change.

And actually, there are a lot of questions about whether the systems that we have are actually the systems that we should have. And classics and the ancient world is one way of starting to unknot some of that thread.

Discussion

Liz Gloyn gives lots of potential answers to this question in the interview, but the three that stood out in particular were:

- Monsters help us to articulate our fears, especially the fear of not being in control of the natural world.

- They give a physical shape to societal prejudices, and allow us to understand the prejudices that societies have towards those they consider to be their ‘others’ (which are often racist and xenophobic).

- Monsters allow us to reflect on what makes us human. By reflecting human fears, ancient monsters encourage us to compare our fears in the modern world with the fears of ancient people. They invite us to see ourselves as both similar to (in some ways) and very different from ancient people.

Monsters are not the only hybrid creatures that you might meet in ancient myths. Heroes, too, are usually part human and part god or goddess. Unlike monsters, heroes often take a human form, but they sometimes have special abilities and challenges as a result of being partly divine.

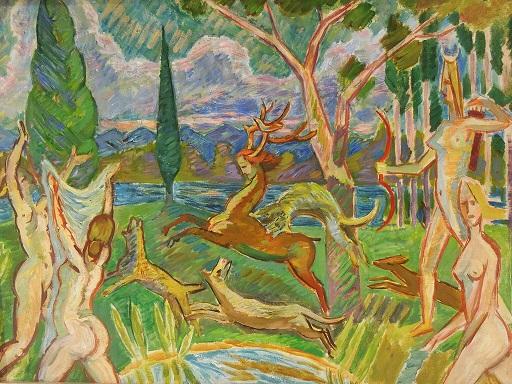

Ovid’s transformation stories engage with the complexity of hybrid beings frequently. Even after transformation into animals or plants, his characters keep hold of certain aspects of their humanity. This complicates the question of what a human is. Would you behave differently towards an animal – like a deer or a cow for instance – if you knew that it might once have been a human, or might still be a human internally? In the next section you will read a story that engages with exactly this question.