2.2 Ovid and his world

Let’s read Ovid’s creation story together and compare it with the one you read earlier.

Activity 4 Ovid’s creation story

In this activity, you have been given six fragments of Ovid’s creation story that have been muddled up so that they are no longer in the order in which Ovid tells the story. Put them in the order that you think Ovid’s story might follow. You might want to use the engraving in Figure 6 to help you. It shows how a much later reader of Ovid’s story thought it should be best represented, and includes images of the story fragments you have been given.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

-

Fragment 3

-

Fragment 2

-

Fragment 4

-

Fragment 6

-

Fragment 1

-

Fragment 5

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.A god separated out all of the parts of the universe, sifting the land from the sky and squeezing the air out of the sea. He hung the stars in the sky and ordered the whole world. He made the tides rise and fall so that the sea set the rhythm for the day.

b.Zeus overthrew Cronus, the Titan who thought himself to be king of the gods. The Golden Age turned to Silver, and after that followed the Bronze Age in which weapons were invented and a huge war broke out between the gods and the Titans.

c.Zeus sent an enormous flood covering the whole of the earth. All mortals were killed as punishment for having gone to war with the gods. Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha were the only humans left alive, floating in their little boat.

d.Before the world began, there was nothing but a huge formless void which was called Chaos. Earth and sea and sky were all mixed up together in the darkness, and cold was mixed up with hot, wet with dry and light with dark.

e.Humans were made, moulded from clay by Prometheus the Titan. Whereas other animals walked on all fours, humans were made to stand upright and were given the ability to think abstract thought.

f.The first age of time was called the Golden Age. Goodness characterised this age, and everyone did what was right without needing laws or punishments to keep them in check. There was no need to plough the land or farm animals because the earth simply gave up food of its own free will.

- 1 = e,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = f,

- 4 = c,

- 5 = d,

- 6 = b

Now that you have the order of the story, you will be able to compare it with the story of The World that Came from a Shell that you read earlier.

Activity 5 Comparing cosmologies

Referring back to the notes you made in Activity 3, write down one difference and one similarity between the ancient story Ovid tells and the story of The World that Came from a Shell that you read earlier.

Discussion

One point of difference that may have stood out to you from comparing these two stories is the fact that for Ovid, the beginning of the world is a story of decline. He explains how the perfect ‘Golden Age’ falls into war, corruption and exploitation of the earth. The story of The World that Came from a Shell, by contrast, is structured as a progression out of the darkness and into the light. Things improve for Ta’aroa and his brothers and sisters once the world has been created.

You may have thought that the most striking similarity is the way that the multiple gods in both stories are family relations, with each god and goddess having a specific responsibility in the world. In both stories, the gods have to fight for their power; it is not automatically given to them. You might well have come up with different suggestions for this activity, as there are many possible answers!

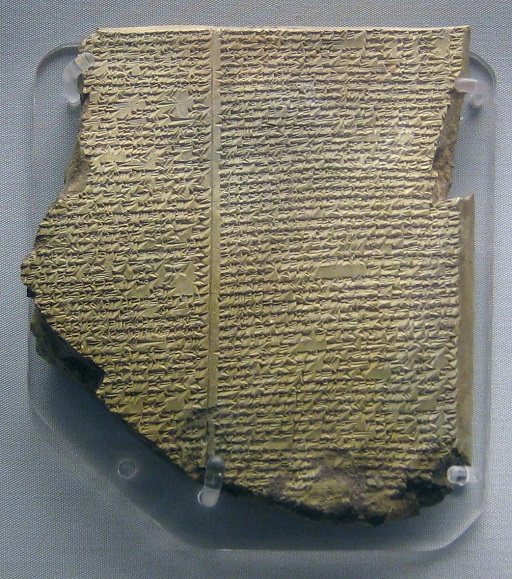

There are many more similarities between the cosmology stories that circulated in the ancient world than you will have the time to delve into as part of this course. One example is the flood, which you learned was a key part of Ovid’s tale of how the world began. It was also a particularly frequent feature of these types of stories. It appears, for instance, in the stories from ancient Mesopotamia (the ancient region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, covering parts of what is now Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Syria and Türkiye). In these stories – like in Ovid’s story – the flood functions as a way of renewing the world, and there are very few surviving humans. You might even be able to think of other creation stories that share this same flood motif.

Ovid’s poem about transformation begins with the creation of the world, or rather with the transformation from nothing into everything. This opening story in the Metamorphoses also asks the first one of the epic’s big questions: how did the world come to be? Now you will leave this question behind and follow Ovid’s own description of his poem a little further. As you read in Activity 1, Ovid says that his poem will take us ‘from creation to my own time’. You’ll explore Ovid’s ‘own time’ in the next section, and find out what (if anything!) it is possible to know for sure about Ovid’s own life.