6 Actaeon’s transformation

Ovid tells the story of Actaeon in Book 3 of his poem The Metamorphoses. The story is particularly interesting for the question you have focused on in the previous section: what makes a human human? In the story, the hunter Actaeon is transformed into a stag by the goddess Diana. After his transformation, however, he still seems to have some of the qualities that we might think of as human. He is upset and tries to shout using recognisably human language, but because he is now a stag he is unable to speak.

Many modern artists have responded to Ovid’s story by making Actaeon the stag look recognisably part human. Chris Ofili’s version in Figure 18 is quite abstract, but you can see that Actaeon is standing on his hind legs in an upright human posture. You may wish to compare this version of Actaeon with the depiction of Actaeon before his transformation on the tapestry from Egypt in Figure 17. Art works often freeze the myth at a particular moment, right in the middle of Actaeon’s transformation – like the ancient art work you will examine in the next activity.

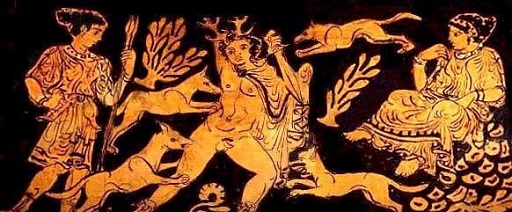

Let’s look now at how this transformation is represented in ancient art. Here, you will study an ancient vase painting by an artist whose name is not known. Scholars refer to this artist as ‘the Choephoroi Painter’, because of another famous vase that they painted which is decorated with a scene from a play called Choephoroi. The Choephoroi Painter lived in Lucania (central Italy) in the 4th Century BCE. The vase is tall, with two long handles and was probably used to hold wine.

The vase is decorated with multiple different mythological scenes. In the next activity you are going to focus on the one that is at the top of the pot, around its neck. You will zoom in on this mythological scene so that you can explore it in more detail.

Activity 12 Decoding a mythical image

Using the zoomed in picture above, write a description of this scene in five bullet points. Try to take note of as many of the details as possible, but make sure that you are describing the image rather than interpreting it. Use only the information given to you in the image itself and make sure that you do not jump to conclusions about what you are seeing based on external information.

Discussion

There are a number of interesting things you might have noticed about this scene. For example:

- There are three figures in human form, one on the left and one on the right, and one in the centre.

- There are four dogs surrounding the central figure, who seem to be biting at the figure’s flesh.

- You can see the shapes of leaves and plants between the figures.

- The figure on the left is holding a spear and is dressed in a shorter dress than the figure on the right.

- The figure in the middle is holding a sword, and there are small antlers on the top of his head.

So far you are not yet able to determine which story this pot is depicting solely by looking at the visual evidence of the pot. To find out more about the story that it depicts, you will need to examine a different kind of evidence. Combining evidence of different types is a crucial skill for the study of the ancient world.

The piece of evidence that will fill in the missing pieces so that you can understand the story that is being depicted on this pot is found in a passage from Book 3 Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In the next activity, you will read this story. Ovid has been translated many times between his own lifetime and the present day. In this activity you will compare two translations. The first is a recent translation (2022) by Stephanie McCarter. The second is a translation that was made in the early modern period by Arthur Golding. You will also have the opportunity to develop your reading skills by examining this more challenging literary text.

Arthur Golding translated Ovid’s Metamorphoses in 1567. His translation is still famous today because it was read by William Shakespeare, who used it to inspire his plays. The two translated versions tell the same story about Actaeon, the unlucky nephew of King Cadmus who is punished by the goddess Diana (who is called Phebe in Golding’s version), for making a terrible mistake. You will see that Golding wrote in a very different style to McCarter’s more modern version.

Note on reading older texts: English spelling is not consistent across time, which means that older texts can spell words in ways that we are not familiar with today. This text was first published in 1567, which means that you may not recognise the spellings of some of the words. A useful trick when dealing with older texts with archaic spellings is to try to read the text out loud, if you are able to. Sometimes you will recognise a word by ear, even if it looks very different to how you would write it in modern English.

Activity 13 Translating Ovid

Read this passage from Stephanie McCarter’s Metamorphoses. Keep a note of the main plot points of the story so that you know what is happening in the myth.

Note that ‘Gargaphie’ is the name of a spring and valley near Mount Citheron in Greece.

There was a valley thick with pines and slender

cypresses, named Gargaraphie and sacred

to girt Diana. Deep within a recess

there was a woodland cave no art had made.

Nature, with her own genius, mimicked art,

shaping an arch of pumice and light tufa.

On its right side, a lustrous fountain purled

with shadow eddies. Round it were broad pools

enclosed by grass. The goddess of the woods,

when weary from her hunting, liked to bathe

her virginal limbs in this translucent water.

Arriving here, she hands her spear and quiver

and bow, now slackened, to that nymph who bears

her weapons, while another grabs her robe

as it slips off. […]

Diana bathes in this familiar stream,

when look! His hunt postponed, Cadmus’ grandson

gets lost in unknown woods, steps faltering,

and comes into this grove. Fate guides his path.

As soon as he goes in the spring-soaked cave,

the nymphs, still naked, see the man and pound

their chests, filling the woods with sudden shrieks.

They crowd around Diana to conceal her

with their own bodies. Yet the goddess stands

much taller, and her neck outstrips them all.

[…]

Having no arrows near, she used what was

at hand and splashed that many face with water.

Then, sprinkling his hair with vengeful drops,

she added words that warned of coming doom:

“Now tell how you have seen me nude, if you

can tell.” She uttered no more threats but placed

the antlers of a long-lived stag atop

his sprinkled head. She stretched his neck out long

and added pointed tips to both his ears.

She turned his hands to feet, his arms to legs,

and wrapped his body in a spotted hide

She made him skittish too. Autonoe’s

heroic son takes flight and is amazed

at his own speed. But when he saw his face

and horns reflected in a stream, he tried

to call out “Wretched me!” Yet no voice came.

He groaned – that was his voice. Tears drenched a face

not his. His former mind alone remained.

What should he do? Return home to the palace

or hide inside the woods? His shame prevents

the former but his fear the latter. While

he hesitates, his dogs catch sight of him.

[…]

He flees through places where he’d often chased!

He flees from his own pets! He yearned to shout,

“I am Actaeon – recognize your master!”

The longed-for words won’t come. Barks fill the air.

[…] As they hold down their master,

the whole pack gathers round and bites his flesh

until there’s no room left for wounds. He groans,

sounding not human nor yet like a stag,

and fills familiar woods with wretched cries.

[…] But his companions, unaware,

goad the swift pack with customary cheers.

Their eyes search for Actaeon. Each one vies

to shout “Actaeon!” loudest, thinking he’s

not there. Hearing his name, he turns his head.

They mourn his absence and that, being late,

he’ll miss the spectacle of such a lucky

prize. Though he’d rather be away, he’s there.

He’d rather see, not feel, his dogs’ fierce feats.

All round, jaws sink into his flesh and tear

their master underneath the false deer’s likeness.

Not till he’d died from countless wounds, it’s said,

was quiver-clad Diana’s anger sated.

Now you will read the opening lines of Golding’s Metamorphoses. Read them aloud, if you are able to, so that you can get a feel for the text’s rhythm and the pattern of its rhyme and verse. You might find that this is quite different to modern English poetry! Note down anything you notice about these aspects of the text.

There was a valley thicke

With Pinaple and Cipresse trees that armed be with pricke.

Gargaphie hight this shadie plot, it was a sacred place

To chast Diana and the Nymphes that wayted on hir grace.

Within the furthest end thereof there was a pleasant Bowre

So vaulted with the leavie trees, the Sunne there had no power.

Now read the final lines of this story in Golding’s translation. Pay careful attention to the differences between McCarter and Golding’s translations. Which one do you like best? Write down your answer to this question, and the reason why, in the box below.

He strayned oftentymes to speake, and was about to say,

“I am Actaeon! Know your Lorde and Master sirs, I pray.”

But use of wordes and speech did want to utter forth his mind.

Their crie did ring through all the Wood redoubled with the winde.

[…]

Not knowing that it was their Lord, the huntsmen cheere their houds

With wonted noyse and for Actaeon looke about the grounds.

They hallow who could lowdest crie still calling him by name

As though he were not there, and much his absence they do blame,

In that he came not to the fall, but slackt to see the game.

As often as they named him he sadly shooke his head,

And faine he would have been away thence in some other stead,

But there he was. And well he could have found in heart to see

His dogges fell deedes, so that to feele in place he had not bee.

They hem him in on everie side, and in the shape of Stagge,

With greedie teeth and gripping pawes their Lord in peeces dragge.

So fierce was cruell Phebe’s wrath, it could not be alayde,

Till of his fault by bitter death the ransome had he payde.

Discussion

There are many characteristics of Golding’s verse that you may have chosen to focus on. You may have found it particularly interesting that Golding had chosen to write in rhyming couplets, two lines which end with words that rhyme. You may have felt that this gave a sense of speed to the passage and kept it running quickly on through the drama of the story. The rhythm of Golding’s translation is also interesting. You may have noticed that each line has fourteen syllables, and that’s because he tried to keep strictly to this number of syllables, Golding often altered the word order of the sentence so that it is very different to what we would expect in modern English.

Now that you have explored the story of Actaeon in full, think back to the image on the painted pot that you analysed in Activity 12. You have now experienced the story of Actaeon told in two different media: text and image. In this next activity you are going to think about the strengths and weakness of each of these two different media for conveying stories about transformation. What can a text do, that images cannot do, and vice versa?

Activity 14 Texts and images

Think about the three versions of the Actaeon story that you have engaged with so far – the painted pot and the two translations. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each of these two different media, image and text? Fill in the table below. Try to include at least one bullet point in each box.

| Image | Text | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | ||

| Weaknesses |

Comment

There are many ways to answer this question, as experiencing art is always subjective and you will have your own opinion on the merits and limitations of each medium. Here is an example table:

| Image | Text | |

| Strengths | Visual art can use colour and shape in ways that draw the viewer’s attention and help them to imagine things they might not have ever seen before. | Texts can convey the internal voice of the characters as well as what they are doing. Ovid uses this to great effect in this story, when he tells us that Actaeon in stag form cannot speak (‘his only voice was a groan’) but still manages to communicate to us what Actaeon would have said if he could (‘what has happened to me?’). This helps the reader to empathise with Actaeon. |

| Weaknesses | Images are static and so it is difficult for them to convey change that happens over more than a single moment. The artist must therefore choose a moment in the transformation to paint, and cannot show the process occurring over time. | Texts tend to focus on the main characters in the scene – if the poet had to describe what every character was doing, the story would become very long! It therefore is not always possible to know in detail what the other characters (for instance the women who are with Diana in the woods) are doing. |

The transformation of Actaeon has been frequently represented not just in text and art in the ancient world, but across many different media in the modern world too. Different artists and creatives have responded to the myth in different ways, drawing out particular resonances from the ancient story and creating new ones that speak to them and their modern audiences. In the next section you will discover an approach that is known as ‘classical reception’, which you can use to study the way that ancient stories change their meaning as they move through different versions, reimaginings and adaptations into the modern world.