3 Hallucinatory reading

3.1 Details

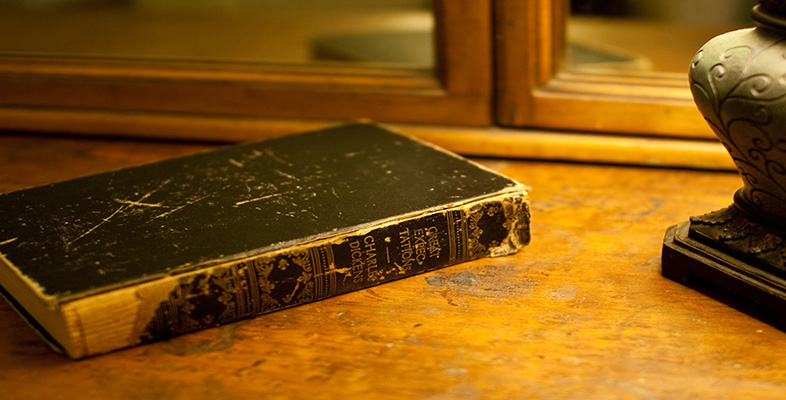

Dickens employs popular sub-genres in a way that tries to persuade his readers to accept that there is another manner of stating the truth or, indeed, as we may see it now, that there are other kinds of truth, at a time when the trend was to be ‘frightfully literal and catalogue-like’. In practice, he does provide the kind of ‘superfluous’, ‘useless’ or ‘concrete’ detail crucial for what the critic Roland Barthes has usefully identified as ‘the reality effect’, an effect at the basis of narrative from the nineteenth century onwards. Without this element of depicting detail, the illusion of the real cannot be sustained. It is easy to find examples in Great Expectations. Almost at random (the randomness confirms the point), I might mention the sack of peas the narrator informs us is present in Pumblechook's front office, and on which his shopman takes his ‘mug of tea and hunch of bread-and-butter’ at eight o'clock on the morning that Pip and the pompous corn-chandler have breakfast, before Pumblechook delivers him to Satis House (p.53). Despite the gothic overtones of her first appearance, the illusion of everyday reality is sustained even in Miss Havisham's odd environment by, for example, added details of her jewels and trinkets, her ‘handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a prayer-book, all confusedly heaped about’ before her looking-glass (p.56).

Of course, such details are functional in other ways, adding something to the significance of each scene and character. Pumblechook is always associated with food and Miss Havisham is at least as confused as her ornaments, which here also signify the halted preparations for a wedding. Other novelists of the time similarly attempt to create the effect of reality with, at its best, a realism of detailed description that seduces the reader precisely through its detail. For example, we are told that a ‘necklace of purple amethysts set in exquisite gold-work, and a pearl cross with five brilliants in it’ (1994 edn, p.12) attracts the eye of Dorothea Brooke, who is introduced to the reader in the opening chapter of Eliot's Middlemarch (1871–2). In this case the detail also serves to confirm and develop the idea of a character whose psychology and background has just been given to the reader at some considerable length, over four pages.

Pumblechook's shopman has no further role in the novel by Dickens, and although Pumblechook's association with seedcorn continues – towards the end of the book his mouth is stuffed full of flowering annuals by the journeyman Dolge Orlick (p.461) – his inner life is never analysed. What about Miss Havisham, whose role is more central? Is her inner life offered to us? I think it should be clear that, despite the shared ground of realist detail, what Dickens intends to convey with details such as the trinkets and other paraphernalia with which he surrounds Miss Havisham is rather different from the use of detail by a novelist like Eliot. Dickens prefers not to analyse Miss Havisham's mind or feelings or personal history; instead, he presents us with a complex, highly suggestive image of what she is, and may become.