1 Rugby – an introduction to contemporary Wales

Hugh Mackay

In recent years the distinctiveness of Wales, in terms of its institutions and culture, has grown considerably. In 1982 Sianel Pedwar Cymru (S4C), the Welsh fourth television channel, came into existence, the Millennium Stadium opened in 1999 and the Wales Millennium Centre (where the Welsh National Opera is based) in 2004, and the Encyclopaedia of Wales was published in 2007. Crucially, the first members of the National Assembly for Wales (NAW) were elected in 1999 – since when we have seen the development of a raft of Welsh policies and bodies, in both the government and civil society. These developments are both cause and effect of how people in Wales see themselves, of how they identify with the nation – and these contemporary features of Welsh culture also shape how others see Wales and its people. Traditionally, stereotypes of Wales held by those in England have been largely pejorative (Taffy as a thief, etc.) and people in Wales have commonly referred to themselves as lacking in confidence about their nation. Today, conceptions of Wales and its people are changing.

In many ways the old icons and stereotypes live on – miners and chapels are in decline, but sheep, choirs, leeks, daffodils and druids remain prominent. Representing more of a break with the past are the Stereophonics, Manic Street Preachers, Dafydd Thomas (the only gay in the village of Llanddewi Brefi in Little Britain), Catherine Zeta-Jones, Rhys Ifans, Ioan Gruffudd, Julien Macdonald, Stacey Shipman (from Gavin and Stacey), Russell T. Davies and Dr Who, who all provide a more modern image of Wales. Alongside the new, old icons, celebrities and institutions endure, but they take on new forms and meanings, they become accented in new ways. Shirley Bassey has appeared at Glastonbury and Tom Jones continues to reinvent himself. Rugby is another example of this; it takes place around the globe but has a very particular significance in Wales, where it has been the national game since before the start of the 20th century.

With this in mind, the aims of this section are to:

introduce you to the subjects addressed in each of the following sections

use the sport of rugby as a prism, or lens, to introduce these subjects.

Like Wales, and Cardiff especially, rugby has changed enormously in recent years. One journalist attributes to Gavin Henson, the charismatic player who made his international debut in 2001 and was the star of the team that beat England in 2005, a key role in transforming dominant images of rugby in Wales:

He has almost single-handedly ushered the Welsh game out of the age of scrubbed-scalp, gap-toothed boyos into the new one of Cool Cymru peopled by those such as pop group Super Furry Animals and divas Katherine Jenkins and Charlotte Church.

Far from the consequence of one player, of course, there is much more to how rugby in Wales has changed in recent years. It has taken a new and distinctive form in becoming professional, regional and based at the Millennium Stadium. The stadium, in the centre of Cardiff, the capital city, has become an icon of the cityscape and a symbol of the nation. By examining rugby, we can make sense of much about contemporary Wales.

Citizens commonly identify with their nation in the context of major sporting events: imagining the nation is easier when there is a national team playing another nation (Hobsbawm, 1990). Rugby in Wales is a particularly strong example of this phenomenon, being perhaps the main thing that unites people in Wales. In many ways rugby in Wales defines what Wales is and what people in Wales share. From outside Wales, too, it is the rugby that commonly defines the nation – with the sport providing both widespread interest and one of the few positive associations of outsiders’ perceptions of Wales. Particularly for people in Wales, rugby is, and its star players are, seen as embodying the essential characteristics and values of the nation – egalitarianism, meritocracy, patriarchy and classlessness (Evans et al., 1999). It is often said that the mood or confidence of the people of Wales, and Wales as a nation, rises and falls with the fortunes of the national rugby team.

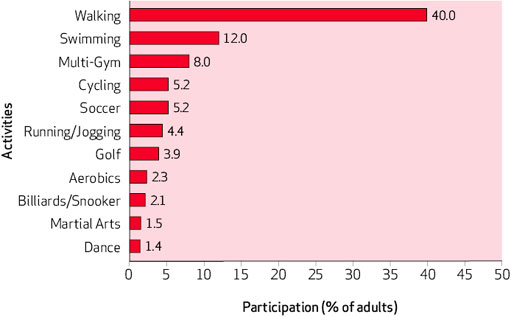

Perhaps remarkably, it is not the case that large numbers of people play, or even watch, rugby in Wales – except when the national squad is playing (especially in the Six Nations championship [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ). Figure 1 shows the most popular sports activities in Wales – with no reference to rugby because the rugby figure is so low that it is off the bottom of the table. Rugby is played by 2.4 per cent of men in Wales, which means about 1.2 per cent of the population. Soccer and cycling are more than four times more popular, and about ten times as many people swim.

In a sense, though, these figures are misleading, in that we might distinguish between recreation or leisure activity (such as walking) from competitive sport, but to an extent the boundary is blurred. We can also consider spectating: about three times as many people watch Cardiff City play football as go to watch one of the four professional regional rugby teams (the Newport-Gwent Dragons, Cardiff Blues, Ospreys and Scarlets). However, if we add the television audience to this, we find more mass involvement in the game. (Undoubtedly, more opportunities to watch rugby on television has reduced the number of spectators at matches). But, notwithstanding the low levels of participation (and even spectating, below the international level), it is through supporting the national rugby team that people in Wales express their belonging to the nation and their pride in it. This does not happen in relation to other cultural events and phenomena, such as the language or music.

Activity 1

Examine Figure 2, photographs taken at the Millennium Stadium on rugby international days. Note what these images tell us about the nature and role of rugby in Welsh society and culture.

- What do they tell us about identities and differences?

- What are other common images or representations of such occasions?

I make no claims to be providing a definitive social science account of the phenomenon of rugby in Wales, but in this section I am using this sport as a way of introducing core aspects of difference and connection in contemporary Wales.