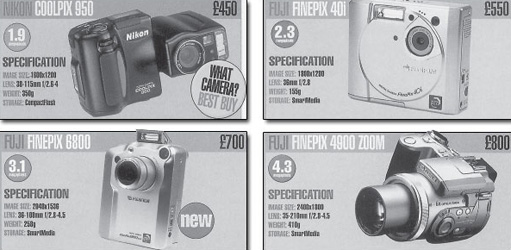

4.2.2 Figure 9b: A selection of 35 mm digital cameras

Question

What do you think is the main difference between the appearance of the 35 mm SLR film cameras and that of the digital cameras in Figure 9?

Discussion

There is considerable variety among the digital cameras. At first glance the Fuji Finepix 6800 resembles a hand-held computer; the Fuji Finepix 40i looks to us like a portable CD player and is in fact an MP3 player as well as a digital camera; and the Nikon Coolpix 950 is perhaps too radical a design to be mistaken for anything else. On the other hand, the Fuji Finepix 4900 looks much more like a 35 mm SLR film camera. This variety and sense of experiment is consistent with the digital camera industry being in its introductory phase. Manufacturers seem undecided whether a digital camera should look like a computer with a lens or a camera with some data-processing software. By contrast, it seems to us that the 35 mm SLR cameras are remarkably similar in appearance and they are also similar in technical specification. Standardisation is evidently lacking among digital cameras. Product standardisation is symptomatic of a move to the growth phase of the industry life cycle. Once firms have standardised the product, they can also standardise the manufacturing process and move to production on a large scale.

Question

What advantages will this move to production on a large scale confer on firms in the growth phase of the industry life cycle?

Discussion

The advantages of large-scale production, summed up in the concept of economies of scale, or increasing returns to scale (Section 3.3), generate a revolution in industrial structure once the expansion of demand gets under way. On the supply side, increasing returns to scale at the growth stage of the cycle can be exploited by the largest and most efficient firms as they compete and survive. Those firms that have failed to keep pace with changing opportunities exit from the industry; that is, a ‘shake-out’ takes place. This contraction in the number of firms means that the industry exhibits a greater degree of concentration as a few large firms dominate the industry. For example, from 1909 to the mid 1920s the number of firms in the US automobile industry fell from 271 to approximately 50 and the number of firms in the US PC industry showed an equally dramatic decline during the years from 1973 to 1999.

How might this be explained? On the demand side, the fall in average costs resulting from increasing returns makes it possible for the firm to reduce the price it charges for the new product. This sequence of events was encountered in the extract from The Economist's survey of the new economy at the beginning of Section 1. The suggestion was that new technologies are a major cause of the decline in costs and hence in prices that enables large numbers of consumers to buy safer cars, personal computers and so on. In terms of the model of market demand explained in Section 2, the fall in price leads to a movement along the market demand curve, bringing the product into the range of many more consumers. This is reinforced by a shift in the market demand curve caused by a change in socio-economic influences, in particular the demonstration effect that describes the tendency of people to imitate the consumption decisions of those who have already bought the product (Section 2.3).

The phase of maturity is reached as the market approaches saturation and replacement demand becomes important. By now there are many similar products for consumers to choose from, as they replace their first car or washing machine – or 35 mm SLR camera – and price exerts a major influence on demand. By the mature phase, the product has become well established and most of the consumers who would like one have already acquired it. The quantity demanded is therefore relatively stable and this is reflected in a flattening of the curve in Figure 8. Firms now have to work hard to reach those consumers who still have not bought the product and to create a demand for replacement purchases. The UK domestic appliance industry provides a good example of this phase. Most of the consumers wanting to own a refrigerator now have one and so the main source of market demand lies with consumers setting up home for the first time, and those needing to replace old equipment. Since there are plenty of very similar products available, price is a key determinant in deciding which one to buy.

On the supply side the focus of the firm's attention therefore shifts to process innovation aimed at securing reductions in the average cost of production. For example, Henry Ford found that the way to drive down costs is through the introduction of innovative new manufacturing processes. The firm that fails to innovate and to adopt industry best-practice technologies of production soon finds that it cannot compete with the lower prices offered by its rivals and is forced to exit the industry. In these circumstances the aim of investment may be to enable a firm to ‘catch up’ with its competitors by introducing the best available technology already in use elsewhere. A good example of this is provided by the German car manufacturer BMW when it took over the Longbridge car plant in the UK. BMW brought the factory up to date with the technologically advanced methods of car production introduced into the UK when the Japanese firms Nissan and Toyota set up new factories near Sunderland and Derby respectively.

Finally, the industry enters into decline when new industries with new products embodying superior technology render the old industry's products obsolete. This phase may be brought on by further product innovation giving rise to a new industry with its own introductory phase so that radically new products replace the obsolete ones. For example, the development of synthetic materials in the 1960s meant that a wide range of industries using ‘natural’ materials went into decline. Some of the firms in these industries, such as carpet manufacturers, were able to draw on the new materials to reinvent their products, but others disappeared altogether as demand for their products dissolved.

Each stage of the model of the industry life cycle presented above is fixed and distinct. In reality, the boundaries between stages in the development of an industry are blurred and can be difficult to observe in a short time horizon. The length of the life cycle also varies with the extent to which the products it makes can be reinvented. The personal stereo industry offers an example. By the 1980s, many consumers already owned a personal stereo that played audio-cassettes. With the arrival of new technologies for recording music on CDs, consumers shifted from cassettes to CDs in order to benefit from better recording quality. This stimulated a replacement demand for personal stereos that could play CDs, extending the life cycle of the personal stereo industry.