4.3.1 Knowledge and learning in the industry life cycle

In Section 3 we described technology as ‘given’ to firms. Now let us reflect on that idea. We can think of technology as consisting of bodies of knowledge necessary to produce artefacts. An appreciation of the importance of knowledge to economic activity is not new, for it was recognised by the eminent economist Alfred Marshall, who wrote that ‘Capital consists in a great part of knowledge and organisation’ (Marshall, 1925, p. 138). What Marshall meant can perhaps best be understood by considering two ‘thought experiments’ broadly similar to those conducted by the philosopher Sir Karl Popper. In the first, all human artefacts, and hence all capital equipment, are wiped out in an extraordinary natural disaster. Human beings survive unharmed and set about constructing their capital stock, and other artefacts, all over again. This is an immense task but in a decade or so the job is done. In the second thought experiment we imagine once again that all capital equipment is destroyed. The difference is that this time human knowledge is also lost. All memories of how to build lathes, computers, robots, cars, combine harvesters and all the other machines the human race has ever invented are annihilated and so too are all the skills acquired in learning how to use them. The human race effectively returns to a much earlier period in its evolution when the capital stock consisted perhaps of stone tools. Even supposing that history repeats itself and people eventually reinvent the technologies leading up to the capital stock of twenty-first century humanity, it would take thousands of years to get back to where we were. The hardware is important but it is human knowledge that really matters. Learning how to use the hardware most effectively is therefore a crucial capacity for firms.

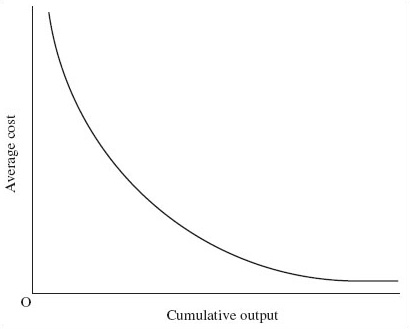

The ‘learning curve’ captures the idea that turning technological change to competitive advantage is a skill that has to be learned like any other. Figure 10 depicts this idea. It shows a fall in average cost that occurs as learning takes place over time after the firm starts up in production. This figure looks rather like the LRAC curve in Figure 6 (c) but depicts a different relationship between output and costs. The horizontal axis, labeled ‘cumulative output’, shows the output a firm produces each year added together over time. This contrasts with the SRAC and LRAC diagrams in Section 3, where output was measured per time period, such as a year, and the diagrams picture the firm's costs at any given output per year. In Figure 6, a firm might move left or right, depending on its output decisions for the year. However, in Figure 10 you should think of the firm as moving rightwards over time, since each year it continues in business, cumulative output will necessarily increase.

When a firm benefits from learning-by-doing, it is said to be ‘moving along the learning curve’ or gaining from ‘experience effects’. Learning-by-doing refers to a fall in unit costs as cumulative output increases. Imagine that the production process involves the use of a new machine. When a worker first starts to operate the machine, lack of familiarity means that mistakes are made and progress is slow. However, the worker learns from these mistakes and as the hours spent operating the machine increase, productivity improves, that is, more units of output are produced per unit of input. The more cumulative output is produced, the more efficiently it is produced. The cost of producing a unit of output therefore declines as cumulative output increases, as Figure 10 shows.

Learning effects are not confined to assembly-line tasks but can occur throughout the firm wherever repetition gives rise to experience. Their significance in the industry life cycle is greatest when firms are learning how to use new technology. This occurs both in the introductory phase, as firms experiment with new products, and in the mature phase, as firms learn how to use new processes to improve the manufacture of a standard product. As the point is reached when all the cost savings derived from experience have been extracted, there is a flattening of the learning curve (Figure 10). From then on the firm diverts its attention to other ways of reducing its costs as a means of gaining an advantage over rivals.

A firm's capacity for learning how to use new technology depends in part on whether innovations build on its existing strengths or render them obsolete. Many historical studies have documented how technological change (process or product innovation) does not evolve in a continuous and smooth manner but discontinuously. A long period of incremental change may be punctuated by episodes of radical change. These discontinuities that are introduced by technological innovation can be classified as either ‘competence enhancing’ or ‘competence destroying’ (Tushman and Anderson, 1986).

To understand this, we need to recognise that once we allow firms to learn and innovate individually, we have moved away from the model of the firm presented in Section 3. That section modelled a ‘representative’ firm among very similar firms. Once firms can learn, we move away from this approach, towards modelling firms as diverse organisations that develop distinct capabilities or competencies over time. Competence-enhancing innovations are innovations that develop new products, or improvements to existing products, which build on a firm's existing competence and strengthen its market position. This cumulative ‘success begets success’ dynamic causes the market structure to become more concentrated, stable and less friendly for new firms:

Existing firms within an industry are in the best position to initiate and exploit new possibilities opened up by a discontinuity if it builds on competencies they already possess … the rich are likely to get richer.

(Tushman and Anderson, 1986, p. 444)

Competence-destroying innovations have the opposite effect. They develop new products or changes in existing products which require completely new skills and knowledge to be developed. These innovations disrupt industry structure, rendering current capabilities obsolete. Existing firms, set in the old way of doing things, are often not quick or ready enough to adapt to this radical change, allowing new flexible firms (not always small) to enter, remaking industry structure – and perhaps starting a whole new life cycle. Innovation can therefore either stabilise or destabilise industrial structure.