3.2 Technology and costs in the short run

Advertising leaflets are dropping through letter boxes around the UK, as we are writing this chapter, from cable suppliers trying to attract new customers for their services. They promise to provide a telephone line, a bundle of television channels, an Internet connection, home shopping and movies-on-demand, all at a ‘bargain price’. These leaflets raise some interesting questions. How does expanding output of cable services by selling to new customers make it possible to offer them for sale at a lower price? What happens to the costs of producing cable services as the firm increases its output of them?

In analysing the costs, technology and output of firms, economists create a model of the typical or representative firm. A firm is an organisation that buys inputs, such as land, labour and capital, and transforms them into an output of goods and services for sale. We call these inputs to the firm's production process factors of production.

A firm that wants to expand output is likely to need more inputs. For example, in order to increase output the cable supplier would probably recruit more workers, such as the technicians who install cable boxes in customers’ homes and the telephonists who respond to customer enquiries. It might also need to buy in more of the equipment used by these workers, such as telephones, computers and engineering tools, and it might need to rent more office space. In other words, the firm increases its input of factors of production, namely labour (the technicians and telephonists), capital (telephones, computers and engineering tools) and land (office space). The firm is assumed to have done this by purchasing the additional inputs it needs from the relevant factor markets, for example by recruiting new workers in the labour market.

The firm can combine factors of production in various ways to create output, but is limited by the technology available to it. The best production methods available to the firm are summarised in its production function, which identifies the maximum output a firm can produce from each available combination of inputs. We can write it out using algebra in exactly the same way as we wrote out the demand function in Section 2:

This says that the firm's output (Q) (the dependent variable) is a function of the various factors of production (the different Fs, up to any number ‘n’ of them) such as land, different types of labour and machinery (the independent variables). This production function is the firm's technology. The firm is assumed to do the best it can with its inputs, without waste. If there is technological change, the firm can get more output from its inputs, that is, increase their productivity. In the models we discuss in this section all firms have access to the same technology.

The firm's objective is not to produce maximum output, but rather to make as much profit as possible. However, reducing costs is an important competitive tool in the search for profits, as the cable supplier's offer of a ‘bargain price’ to new customers illustrates. So how do firms’ costs change as output changes? What makes it possible to supply more customers at a lower price? Are there any limitations to this process? The distinction between the short run and the long run helps to answer these questions.

Question

We referred above to the cable supplier recruiting new workers. Can you think of any employers or industries that have found this difficult?

Discussion

In 2001 in the UK the health and education industries were beset with staff shortages and in some areas recruited from overseas. It is likely to take most employers longer to increase the quantity of skilled than unskilled labour. Skills may not be available in the locality and workers may have to be enticed to move from other jobs, involving periods of notice. New workers may have to be trained and the training period may well be lengthy. BBC television reported on 4 September 2001 that Arriva, a UK train and bus operator, had announced the cancellation of up to a hundred services a day because of a shortage of train drivers. Arriva had the capital equipment, the trains, to run the services but could not do so until it had increased the amount of skilled labour at its disposal by training new drivers. In this example the firm is constrained in its response to the demand for rail services because the quantity of one factor of production, labour, is fixed.

Economists describe the situation in which Arriva finds itself as the short run. A firm is operating in the short run when it is unable to change the quantity it uses of at least one of its factors of production. In other words, in the short run the firm can vary the quantity it uses of some of its factors of production but there is at least one which is fixed. The term denotes this constraint on the firm's behaviour rather than a particular period of historical time. The firm's actions take place in actual or historical time and so the short run will eventually come to an end, in Arriva's case when the drivers have been trained in a matter of months. Therefore, the short run, understood as the condition of being unable to change the quantity used of at least one factor, refers to different periods of historical time, depending on the circumstances of each particular firm. Another example from transport illustrates this variety. London's Heathrow, Stansted and Gatwick airports are constrained in responding to rising demand for air travel from London and south-east England by the planning process required before new runways or terminals can be constructed. In this case the fixed factor is capital and the short run is measured in years, perhaps even decades.

Heathrow Terminal 5 to get go-ahead

After an inquiry that began in 1995, the government is poised to give the go-ahead for Heathrow's Terminal 5. It is due to open in 2007, subject to final approval.

(Adapted from The Sunday Times, 4 November 2001, p. 2)

In the short run, therefore, the firm has one or more variable factors of production but at least one fixed factor. How does the firm's output change in the short run as it increases the amount of a variable factor? For example, let us suppose that the cable supplier recruited more labour, such as technicians and telephonists, while using unchanged quantities of both capital and land. Hiring more labour allows it to increase output. Initially, output may rise faster than the inputs of labour. Each additional worker may not need a computer all to themselves and, up to a point, extra workers can share the same office space. So initially increases in the amount of labour may generate larger ‘returns’ in the form of increases in output. At this stage in its expansion of output in the short run, therefore, the firm is experiencing increasing returns to a factor of production, in this case labour.

However, this fortunate situation has its limits. If the firm continues to expand output by increasing the input of labour with unchanged inputs of capital and land, a point will be reached after which the employment of even more workers brings successively smaller increases in output. For example, there may be so many workers that each one spends some time idle in the queue waiting to use a computer. The input of labour is rising faster than output, and the firm is now experiencing diminishing returns to a factor of production. Diminishing returns pose a serious constraint on the expansion of a firm in the short run.

These relationships between inputs and outputs in the short run influence the firm's costs. Returning to the cable supplier, it is now possible to frame a more precise question: what happens to the costs of producing these services as the firm increases its output of them in the short run? To analyse this, we need to distinguish total costs (TC) and the average cost (AC) of production. A firm's total costs are the expenses incurred in buying the inputs necessary to produce the firm's output. Average cost is the cost per unit of output. Average cost (AC) is therefore the total cost of production (TC) divided by the number of units produced (Q):

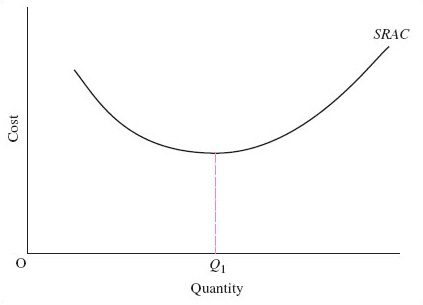

We can draw a short-run average cost (SRAC) curve that models the relationship between different levels of output and average cost (AC) in the short run (Figure 5). Each point on the SRAC curve represents the average cost in the short run (measured on the vertical axis) of producing a quantity of output (measured on the horizontal axis). Output (Q) is measured per time period, such as a year. The SRAC curve is expected to be ‘U’-shaped, as shown in Figure 5. The downward-sloping section of the SRAC curve indicates that as output expands from a low level, average costs in the short run fall. Eventually, however, the SRAC curve begins to slope upwards, showing that at output levels above Q1average costs rise as output increases.

The shape of the SRAC curve arises from the technical constraints on short-run output expansion just described. We assume that the price of inputs is constant. As output expands the fixed cost of the fixed factors of production, such as the cable system itself, is being spread over an expanded number of customers. Increasing returns to a factor of production means that output rises faster than the variable input, so the cost of the variable factor per unit of output falls too. So initially the average cost of production (AC) falls as output rises.

Eventually, however, diminishing returns to the variable factor of production sets in. Output starts to rise more slowly than the variable input so the additional cost required to produce additional units of output starts to rise. Eventually total cost (fixed plus variable costs) will start to rise faster than output: that is, average costs will start to rise. On Figure 5 this happens as output rises above Q1.

To sum up, in the short run the firm's ability to reduce costs as output rises is constrained by diminishing returns. In the long run, opportunities to invest in factors such as plant and machinery mean that the quantity of all factors of production can be varied. How does that affect the firm's costs?