Privacy Harms

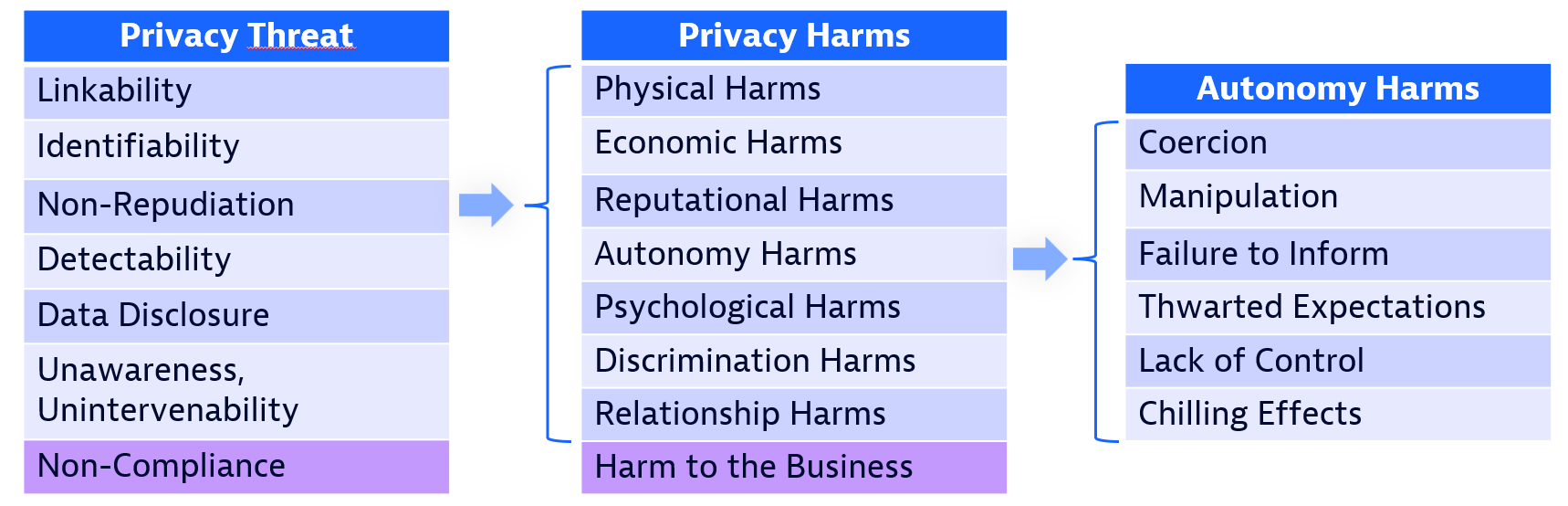

You're now familiar with privacy threats and different ways they can be categorized. But what are their consequences? Do they lead to harm for individuals, and if so, how? Determining this is hugely important. A threat that leads to no harm may be too minor to be worth mitigating in your product. On the other hand, a threat may lead to harm in a way you would never have considered. Similarly, courts have often required that plaintiffs prove some tangible harm occurred to them in order to receive damages in privacy lawsuits. Unfortunately, in the US, courts have used very restricted - and sometimes contradictory - definitions of what 'harm' is. In their recent typology, Citron & Solove identified types of privacy harm that can occur to individuals. We summarize their definitions below. Their aim was to help the US courts make better judgements, but perhaps they can also help us reason about privacy threats.

- Physical Harms - harms that result in bodily injury or death. For example, people have been murdered when their home addresses were disclosed to their stalkers. Another tragic example is the case of abortion doctors being murdered after being doxed by anti-abortion groups. In some countries, individuals face torture or execution if their sensitive personal data - for example their sexual orientation - is disclosed.

- Economic Harms - losing money, or a reduction of value in something you own.

- Reputational Harms - damage to your reputation.

- Autonomy Harms

- Coercion: constraining someone's freedom of choice or behavior, or putting undue pressure on them to choose or behave a certain way. For example, charging an unaffordable fee for anyone to exercise their privacy rights.

- Manipulation: in contrast to coercion - which the person realizes is happening to them - manipulation involves subtly and sneakily influencing someone's behavior. It is the most common type of autonomy harm for consumer privacy. Yet it can be difficult to distinguish between persuasion and manipulation. After all, we all try to persuade others, and sales and marketing of products depend on persuasion. The difference is that manipulation is exploitative, covert, and against the person's best interests. Manipulation takes advantage of a person's weaknesses to rob them of their freedom of choice.

- Failure to Inform: you are not provided with sufficient information to exercise your privacy rights or make informed choices about your personal data (corresponds to Unawareness in LINDDUN).

- Thwarted Expectations: the choices you have made about your data are undermined, for example if you ask to delete your data but it is never fully deleted from the system.

- Lack of Control: inability to control how your data is used (together with Thwarted Expectations, corresponds to Unintervenability in LINDDUN).

- Chilling Effects: being deterred from exercising your rights (for example to freedom of speech, freedom of belief, or political participation). If you are aware your messages are being monitored by the government, for example, you may be more reluctant to express critical views about them for fear of retribution.

- Psychological Harms

- Emotional Distress: a negative emotional response to a privacy violation, such as anger, embarrassment, fear, or anxiety. Prolonged emotional distress can lead to autonomy harms, for example learned helplessness, or physical harms such as self-harm and suicide.

- Disturbance: privacy violations that cost time or energy or are otherwise a nuisance to you, such as spam phone calls.

- Discrimination Harms - receiving unfair or unequal treatment because of a privacy violation. For example, disclosure of a disability might result in you being fired from your job, or prevent you from becoming a resident of a country.

- Relationship Harms - damage to your personal or professional relationships with individuals or organizations, for example loss of trust or loss of respect. This may frequently occur together with reputational harm.

One harm which seems noticeably absent here is the harm of confinement: being imprisoned due to information that was disclosed about you. Unfair imprisonment based on digital evidence is sadly far too common. As we discussed earlier in the course, for example, location data is often used as evidence in prosecution.

Calo's Harm Dimensions

While it's true that you can have a privacy violation without any harm, the reverse is also true, and this is why taking the time to understand your users' privacy expectations is so important. Professor Ryan Calo categorizes privacy harms into two categories (also referred to as dimensions): objective harm, where a privacy violation occurs and directly leads to harm; and subjective harm, where no privacy violation occurs but the users' belief that it did causes them harm. For example, believing you are under observation might have a chilling effect on your behavior. If someone else's actions led you to this belief - for example, they installed a dummy camera in your workplace - then they have caused you privacy harm.

The two categories are distinct but related...The categories represent, respectively, the anticipation and consequence of a loss of control over personal information...The subjective category of privacy harm is the perception of unwanted observation. This category describes unwelcome mental states - anxiety, embarrassment, fear - that stem from the belief that one is being watched or monitored. Examples of subjective privacy harms include everything from a landlord eavesdropping on his tenants to generalized government surveillance...no person need commit a privacy violation for privacy harm to occur.

Many of the harms we associate with a person seeing us - embarrassment, chilling effects, loss of solitude — flow from the mere belief that one is being observed. This is the exact lesson of the infamous Panopticon. The tower is always visible, but the guard’s gaze is never verifiable. As Michel Foucault explores, prisoners behave not because they are actually being observed, but because they believe they might be. The Panopticon works precisely because people can be mistaken about whether someone is watching them and nonetheless suffer similar or identical effects.

Solove's Taxonomy

You may also often come across Solove's taxonomy of privacy problems. This is not the same thing as the typology of privacy harms above. Citron & Solove explain that "problems are undesirable states of affairs. Harms are a subset of problems" and that "Many of the problems in the taxonomy can create the same type of privacy harm." In other words, these problems are privacy threats, which may or may not lead to harm. Your privacy could be violated without you coming to any harm; similarly, a business could be non-compliant without the business suffering any harm such as a fine or negative publicity. A closer comparison point, then, would be LINDDUN rather than the privacy harms taxonomy.

Solove's goal was to make it easier to reason about what privacy actually is by identifying the ways in which it can be violated (problems). We introduce the taxonomy here to contrast privacy problems with privacy harms, and also to provide valuable context: it has been influential in the field, and you will see it referenced in many discussions. The FAIR-P risk assessment methodology we will see in the next section uses it to identify problematic actions that should be avoided.

- Invasions

- Intrusion: disturbing someone's peace or solitude; this is privacy as "the right to be let alone".

- Decisional interference: as the name suggests, this occurs when someone (or a system) interferes with an individual's decision-making, for example showing them only positive or only negative reviews to bias their impression of a product when purchasing.

- Note that, unlike the other categories, invasions can happen without any personal data being involved.

- Information Collection

- Surveillance: observing a person's activities. There are innumerable examples of this online, but one of the most ubiquitous is the Facebook Pixel.

- Interrogation: demanding information from a person, for example unnecessarily requiring a phone number to register for an account.

- Information Processing

- Aggregation: linking multiple pieces of information about an individual to learn more about them (just like Linking from LINDDUN).

- Identification: uniquely identifying someone, for example via their IP address, cookies, or mobile device identifier (IMSI, IMEI).

- Insecurity: failing to secure people's data properly. Note that a data breach or hack does not need to occur for this to be a problem; the problem is that this exposes users to future harm.

- Secondary use: reusing someone's data for a different purpose than they consented to.

- Exclusion: preventing a user from understanding or having control over what is happening with their data (like Unawareness and Unintervenability from LINDDUN)

- Information Dissemination

- Breach of confidentiality: revealing a person's data despite promising not to do so.

- Disclosure: revealing information about a person that is true but harms their reputation.

- Distortion: providing false information about someone. This can happen by accident, for example if an algorithm is inaccurate/biased.

- Exposure: revealing information about a person that exposes them physically or emotionally, such as publishing nude photos or a video of them hysterically grieving. The difference between exposure and disclosure is that exposure does not necessarily worsen our opinion of the person, it just reveals information that social norms dictate should not normally be public.

- Increased accessibility: making it easier to obtain someone's data, for example making their posts on a platform public by default.

- Blackmail: threatening someone with privacy harm unless they meet your demands.

- Appropriation: repurposing someone's identity. For example, you might use someone's writing as training data to fine-tune an LLM, so that the LLM then outputs writing in their style.

Consider:

- Did you notice the overlap with LINDDUN?

- Solove's taxonomy somewhat blurs the boundary between threats and harms. What do you think about the decision to limit 'disclosure' to only information that harms one's reputation? How does this compare to LINDDUN?

- If you're surprised by this definition, reading the paper helps put it into context. The definition must also be balanced against freedom of speech, which is highly valued - and constitutionally protected - in the US.)

- Which do you prefer for reasoning about privacy threats, Solove's taxonomy or LINDDUN?

Further Reading

- A Taxonomy of Privacy, Daniel J. Solove, University of Pennsylvania Law Review (2005)

- Privacy Harms, Citron & Solove, Boston University Law Review (2022)

- Risk and Anxiety: A Theory of Data-Breach Harms, Solove & Citron, Texas Law Review (2016). Interestingly, Citron & Solove also distinguish between privacy harms and data breach harms, saying that the latter are mainly anxiety or risk of identity theft and fraud, whereas privacy harms are much broader and more challenging to reason about. This paper explores data breach harms, if that distinction interests you.

- Recap: Webinar looks at the exceptional nature of privacy harm, Müge Fazlioglu, IAPP - this article summarizes a discussion on how reluctant US courts are to consider subjective privacy harms, in contrast with the EU. One exception is the LabMD ruling, where the FTC did (eventually) succeed in convincing the courts to consider subjective harm.

- Amnesty International Report 2022/23: The state of the world's human rights. Do any of the criminalized behaviors in this report surprise you? Does the software you build process any data that could lead to someone's imprisonment if it is leaked, for example details of users' mental health, sexual orientation, or location?

- See also the Center for Humane Technology's Ledger of Harms, which provides examples of harms caused by social media platforms.