9 Notating pitch using numbers

As noted earlier, there are many kinds of notation in the world, several of which existed long before staff notation. Many of these use written characters to designate notes. For instance, Indonesian gamelan music such as the Sundanese piece (Bendrong) you heard in Section 7.1 is often notated using numbers.

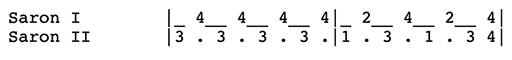

Example 14 below is an instance of notation for Gamelan Saléndro, the ensemble that uses the Sundanese saléndro pitch system introduced earlier. It comes from an introductory guide to Sundanese gamelan by Simon Cook (1992). It demonstrates an interlocking pattern of the kind that might be played by two different sarons, in which saron II plays a note, then saron I, then saron II, then saron I, and so on.

This alternation is represented in the example by means of a kind of sawtooth pattern, with a line in the saron I part when the saron II part has a number, and a dot in the saron II part when the saron I part has a number. The very final note, 4, aligns vertically between the two parts, indicating that the musicians play it together. The example makes use of cipher notation: notation that uses numbers to indicate pitches.

| Number | Name | Distance from singgul in cents | Distance from previous note in cents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5̣ | Singgul or petit | 1200 | 240 |

| 1 | Barang or tugu | 960 | 240 |

| 2 | Kenong or lorloran | 720 | 240 |

| 3 | Panelu | 480 | 240 |

| 4 | Bem or galimer | 240 | 240 |

| 5 | Singgul | — | — |

Table 2 was introduced earlier in Section 7.2. It outlines the names of the notes in the saléndro pitch system as well as the numbers given to them in cipher notation (Cook, 1992). The lowest note (in Western terms) is at the bottom of the table and the highest is at the top.

(You may wonder about the uppermost 5̣ in the table, which features a dot below the number. This symbol represents the note an octave above the lowest 5 in the table. There is a dot below the symbol to indicate that this is a ‘lower’ 5, which is to say one that sounds higher from a Western perspective. The use of dots above or below the numbers in cipher notation allows musicians to represent notes in up to three octaves. For example, they would look like: ![]() .)

.)

With the help of the table, you can see that in Example 14 the player of saron II plays panelu, then the player of saron I plays bem, then the player of saron II plays panelu again, and so on. Audio 6 contains an approximate electronic representation of the passage.

Cipher notation can also be found in other music cultures: the Cameroonian ethnomusicologist Pie-Claude Ngumu devised a system of cipher notation to represent xylophone music from the Centre Region of his country (see Ngumu, 1976; 1980). Cipher notation is easier to grasp than staff notation, so musicians use it in contexts where staff notation would be needlessly complicated.

This is not to say that complicated forms of music take complicated forms of notation and simple forms of music require simple forms of notation. There are plenty of complexities in gamelan music and Cameroonian xylophone music! Rather, it is a matter of numbers being the most efficient and accessible way to designate pitch to musicians working in certain traditions.