4 How we work now

It can be easy to forget that how we worked before the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic has many similarities to how we work now. For many the pivot to remote working involved minimal changes to the work they do, but setting up their offsite workplace was a challenge. Employees and students in the higher education sector became more responsible and accountable for managing how they worked – especially during lockdowns – and had to balance their work against their personal environments and needs. Going forward, a way of working is needed that allows for continued flexibility while meeting organisational needs.

Activity 9: Shifting the way of work

Watch the video in which Jacob Morgan shares insights about how organisations are evolving.

Transcript

Read the article from BBC Worklife – How companies around the world are shifting the way they work [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . Does this feel familiar to your experiences of the changes of ways of working?

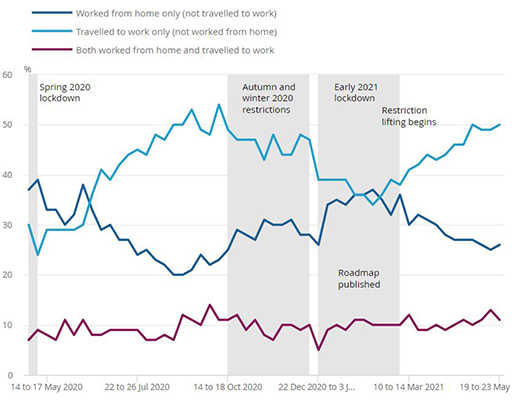

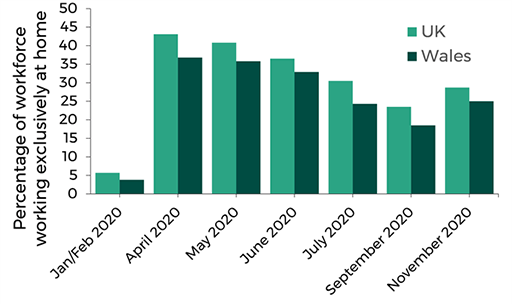

As you can see from the images below, it is important to remember that some individuals’ working patterns did not change: they continued to go on site throughout lockdowns, or were already remote workers.

Notes for Figure 13:

- Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

‘Spring 2020 lockdown’: 23 March 2020 to 13 May 2020.

‘Autumn and winter 2020 restrictions’: 14 October 2020 to 4 January 2021.

‘Early 2021 lockdown’: 5 January 2021 to 8 March 2021.

‘Roadmap for England published’: 22 February 2021.

‘Restriction lifting begins’: 8 March 2021.

- You can explore the interactive version of the image here.

As the skills required to work effectively evolve, the reliance on technology due to remote working and learning has meant that digital, communication and time-management capabilities have had to develop rapidly.

Individuals and HEIs adapted how they worked and had to quickly provide remote learning for their students, and take domestic arrangements into account without the infrastructure to properly support this. This uncertainty has raised concerns about the trust students have in their HEI to provide the services and support they require.

‘UK should pay more attention to the potential relationship between trust and mental wellbeing. Among the more consistent findings in the literature are our results concerning gender, previous financial strain, food security and housing security, all of which have been found to impact mental health and/or mental wellbeing.’

Activity 10: Learning from the pandemic:

Browse the following articles and reports linked below, which explore the impact of the pandemic on HEIs and students. Consider how these reflect your own organisation’s current work practices.

- Lessons from the pandemic: making the most of technologies in teaching

- Student Mental Health in a pandemic

- Student Mental Health: Life in a pandemic

- Remote working – the new normal?

- Remote Working: Implications for Wales

Think about your own experience of the pandemic. How did you adapt, and how did your organisation respond? If you are within an HEI, what was the impact on students?

Make notes in the free text box below.

Answer

At a personal level your experience will depend on your personal circumstances.

For example, I had to shield. From a working perspective nothing really changed as I was already a remote worker, but I changed jobs 4 times during the 2-year lockdown period, due to redundancy, freelancing and securing a fixed-term contract then a permanent role. I home schooled, renovated my house, and on some days relied on the dog walks and coffee from the local café to speak to another adult in person. Shielding has impacted my ability for socialisation. It is only recently that I feel more comfortable to start to mix with others again.

From an organisational perspective, this varied, from being sent ‘care packages’ to feeling completely isolated, with an increasing unseen workload. While also recognising that organisations were adapting daily and starting to find their own way through the uncertainty.

For some people, this rapid and continual adjustment to ambiguity and uncertainty had a significant impact on their wellbeing, thanks to factors such as restrictions forced upon them, concerns about risks to their health, and balancing the demands of their personal lives as they dealt with constant change.

The full impact of this varied depending on personal circumstances. For example, people who had to shield faced the immediate implications of being completely shut off from the world, but in practice they had to consider circumnavigating the rules to do simple things like walk the dog, or even buy food. If you are told you cannot go to the shops, you have to work out other options, such as relying on friends/family to shop for you, online deliveries (if you could get a slot) or council-run food schemes, while having periods of not speaking to or seeing another person in the flesh.

Cultural changes will have occurred in organisations too, especially HEIs, where once thriving campuses became ghost towns, and the demand for online learning provision became a necessity. As a result, more HEIs will now be planning to offer a ‘blended’ approach to learning – ‘which included e-learning with only online formats, a blended approach that mixed online and face-to-face teaching with in-person teaching’ (Ameduni and Ligoro, 2022) – as a standard part of their provision, not just as an emergency response to the pandemic.