2.2.2 Salinity, desiccation and biotic interactions on seashores

Tidal movements ensure that sea-shore habitats are, if not covered by seawater for part of each day, at least subject to spray-borne salt and wind. So, even well above the level of high tides, sea-shore organisms need to be more tolerant of salt than most terrestrial organisms. However, salinity (the concentration of salts dissolved in water) is not the only factor affecting sea-shore species. Seaweeds and shelled animals like limpets and barnacles are adapted to living in a highly saline marine environment, but they suffer desiccation if they are out of water for too long between high tides. In addition, where the shore is in an exposed location (i.e. a high energy environment), sea-shore organisms need to be able to tolerate severe abrasion caused by both wave action and pebble movements.

These factors affect not only which species are present in the intertidal zone, but also their exact location on the shore, i.e. their zonation. The pattern of zonation that results from these environmental factors is then further modified as the result of biotic interactions between organisms, such as seaweeds and the molluscs that graze on them. So, patterns of zonation vary and interpretation of what is found can be rather complicated.

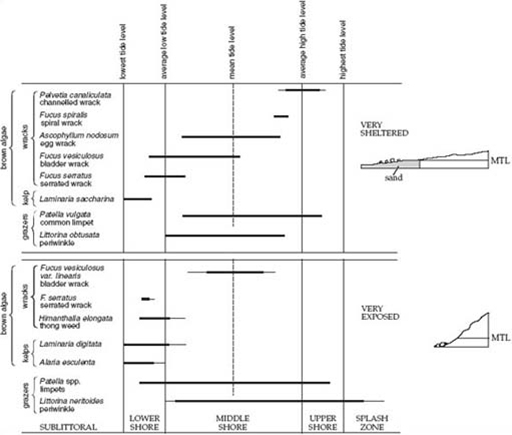

Figure 24 shows the zonation pattern of seaweeds and grazing animals on two rocky shores.

Question 7

Describe the differences between the occurrence and zonation of channelled wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata) and limpets (Patella spp.) on these two shores.

Answer

Channelled wrack does not occur on very exposed shores. Limpets occur on both sheltered and exposed shores, where they show roughly the same upper limit of distribution. However, limpets extend farther down the shore in exposed habitats.

Click to see larger version [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] of image

Channelled wrack is a species that is very resistant to desiccation and can recover even when it loses 96% of its water content. However, it has a relatively low growth rate and so it may not be able to become established on shores where young plants would be damaged by wave action. Other factors affecting the growth and zonation of channelled wrack include its inability to tolerate low light levels (for instance, when covered by the more profuse growth of other seaweeds) and its susceptibility to disease when submerged in water for long periods of time.

Limpet distribution on the lower reaches of sheltered shores is linked to the heavy growth of brown seaweeds, such as wracks and kelps. When juvenile limpets (spat) are released into seawater they must settle on rock surfaces to develop further. If no rock surfaces are exposed there is no place for them to settle.

Question 8

How could the salinity of the environment increase when tides recede and organisms are left exposed?

Answer

As exposed surfaces and organisms lose water by evaporation, the concentration of salt in the remaining water increases.

It follows that organisms occurring in the spray zone, above the level of high tides, may have to cope with an environment in which salinity can sometimes be higher than further down the shore, where the tide is out for only a limited time. However, at other times rainfall can reduce the salinity experienced by these organisms to below that of seawater.