How do we measure sustainability?

The wide range of definitions for sustainability also applies to how it is measured. Sustainability may cross environment, socio-economic, governance and even health and welfare as the “One Health” concept becomes more prominent. It may also include impacts at local, regional and global levels. To appreciate all of these aspects, a comprehensive method of assessment is required. It is extremely challenging to incorporate all of the different aspects and contexts into a single metric or index of sustainability.

Before continuing with this unit, you might wish to listen to this podcast discussion between Professor Dave Little and Dr Richard Newton on Eco-intensification and the circular economy as it provides further context for the methods presented here. Listen directly using the player below, or link to the Podcast website for additional information.

Download this audio clip.Audio player: EcoIntensive_HotFish008.mp3

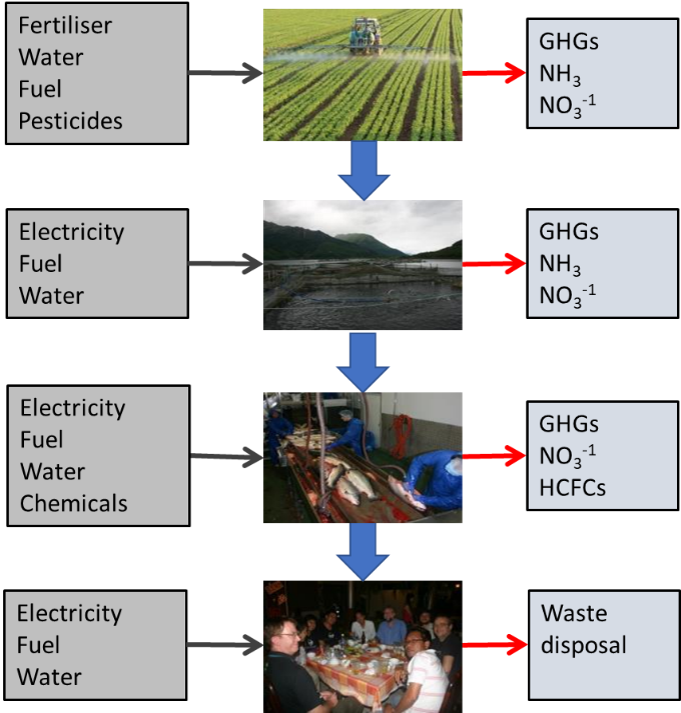

As

shown in previous modules, impacts occur and accumulate throughout aquaculture

value chains (Figure 1). Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a

transferable tool for accounting for the supply chain emissions of products and communicating

them as tangible environmental impacts. The broad supply chain approach ensures

that trade-offs and shifts in impacts are identified. There have also been

attempts to integrate socioeconomic impacts using an approach although data

collection for these types of impacts can be especially challenging. LCA

typically involves a large data set, sourced from producers, literature and LCA

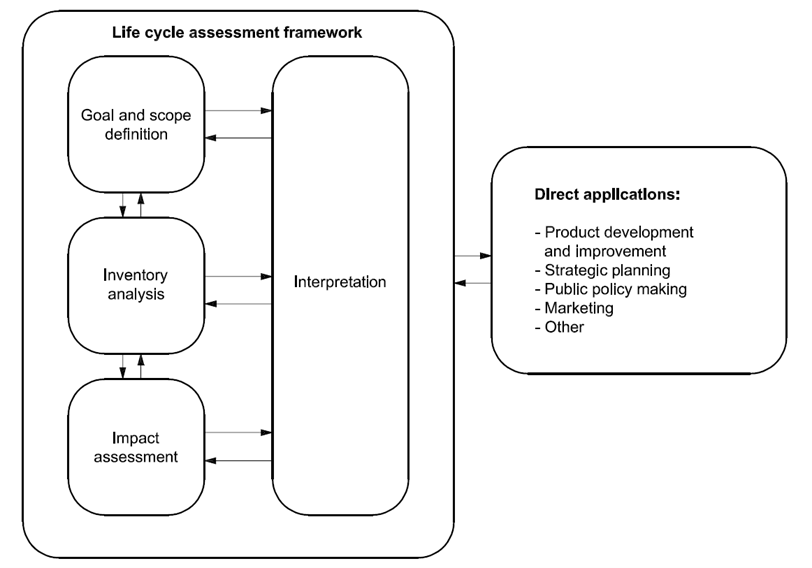

databases which needs careful planning. Steps set out by ISO (2006a; 2006b) are

designed to aid practitioners to plan data collection and modelling and are

described in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of an aquaculture value chain with raw material inputs and emissions

The Goal and Scope phase sets out the basic parameters of the study and is usually dictated by the audience and main objectives, such as commercial product development, planning or marketing exercise, or an academic, independent assessment aimed at policymakers or others. This determines how the results will be used and presented, and their application.

Critical points to be defined during the Goal and Scope are the boundaries of the system, i.e. what parts of the value chain are to be included in the data collection, the reference unit (known as the “Functional Unit”) for the study, the cut-off criteria (what processes will be included or not, usually based on their relative contribution to overall impact), the partitioning procedure between multi-functional processes (how much impact should be attributed to different co-products), the impact categories that will be included and the analytical method.

Inventory analysis involves the compiling

of all relevant input and output data of the production systems within the

value chain under study, within the boundaries defined at the Goal and Scope

phase into the “Life Cycle Inventory” (LCI). It is generally the most

time-consuming part of the LCA as it involves complex survey work with multiple

stakeholder actors, many of which may not have been previously identified. It

is an iterative process that often requires trust and confidence-building

between the data collectors and providers, especially as the data is often

commercially sensitive.

Figure 2. Overview

of Life Cycle Assessment steps according to ISO 14040 (ISO 2006a)

Often the first step is to characterise the systems and flows of materials and value by constructing flow diagrams. Information can be gathered from any previous studies of similar systems and by stakeholder interaction. The flow diagrams provide an initial basis for understanding the most important parts of the value chain and their interconnectivity to inform primary data collection and where the cut-off points might be. The data can be used to determine how many of each stakeholder must be contacted to provide a representative level of data that meet the goal and scope objectives.

The Life Cycle Inventory may be separated into

three parts: 1; primary data that are collected directly from stakeholders via

survey or other means, 2; secondary data that are collected by literature

searches and 3; background data that are contained within LCA databases such as

EcoInvent (https://ecoinvent.org/). Typically, primary data are those relating

directly to the system under study, such as the farm, feed manufacturers, and

processors in the case of aquaculture. It usually includes things like the

amount of feed or electricity used and the composition of the feed. Secondary

data may include more detail on items within the primary data such as on the

growing and manufacture of feed ingredients. As ingredients are often produced

in other continents, it is not feasible to collect primary data for these

processes within the same project. Background data typically include things

like emissions data from engines, energy provision, chemical production, and

raw materials for capital goods such as steel etc that are entries into the

primary or secondary data list. Such background data have been built up and

adjusted over many years by experts in those fields. Data collection is usually

a lengthy and iterative process that goes through an initial cleaning and

quality evaluation process before contacting participants for clarification of

data or further data collection. Data collection from primary sources requires

good relationships with the industry sector from where the data are collected,

which may need to be built through a series of meetings, perhaps facilitated by

strong partners that already have good working relationships within the

industry. Literature data must be found and analysed to identify the required

data. Often several data sources may be available with conflicting information

that must be assessed for its suitability and cleaned to the required level. Data must be

adjusted to take into account the reference flows within the study set out

within the Goal and Scope phase. Other data such as country-specific

electricity mixes and the associated emissions may be sourced from extensive

LCA databases, including e.g. EcoInvent. Data must be further assessed for

quality and representativeness throughout the data collection period. During

the data evaluation steps, the data categories are identified and quantified

into the reference flows of materials, energy and value between the process

nodes within the value chain according to the initial flow diagrams. The data

includes economic flows, which are generally goods or services that have an

economic value, produced in manufacturing processes, or environmental flows

which are either raw material resources or emissions taken from or emitted to

the biosphere.

It is rarely possible to collect

data on all processes in the life cycle of a product and it saves a lot of time

to determine those processes which have little effect on the overall impact

assessment early on after the initial data scoping. Reducing the level of data

collection and hence the time commitments also improves the relationship with

the industry from which it is being collected. In most cases, the cut-off

criteria will be according to impact contribution (e.g. processes that

contribute to less than 1% of emissions are excluded), but processes may also

be assumed if there is little access to data or likelihood of obtaining it. In

such cases, assumptions must be made according to similar processes in similar

systems.