Social impacts

In the following video, Professor David Little highlights some of the key social considerations for sustainable aquaculture.

Consumption value chains that connect the European Union (EU) with the rest of the world is complicated. What comes from the EU, and what comes in from overseas?

Most seafood in the EU is imported, either from wild catch or cultured. We need to look into how those supply chains stretch across the world.

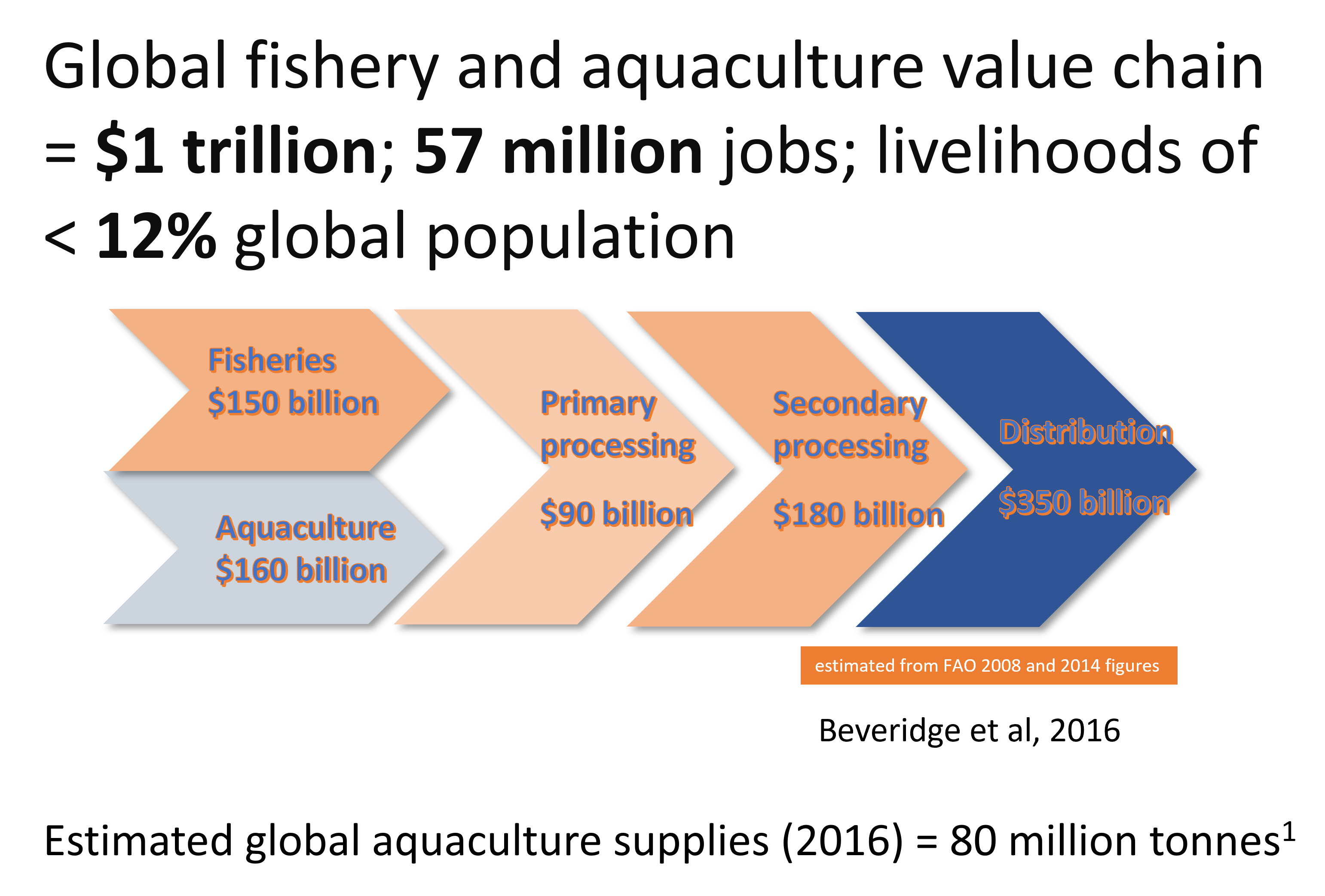

Figure 6: Summary of global seafood value chains in terms of economic value

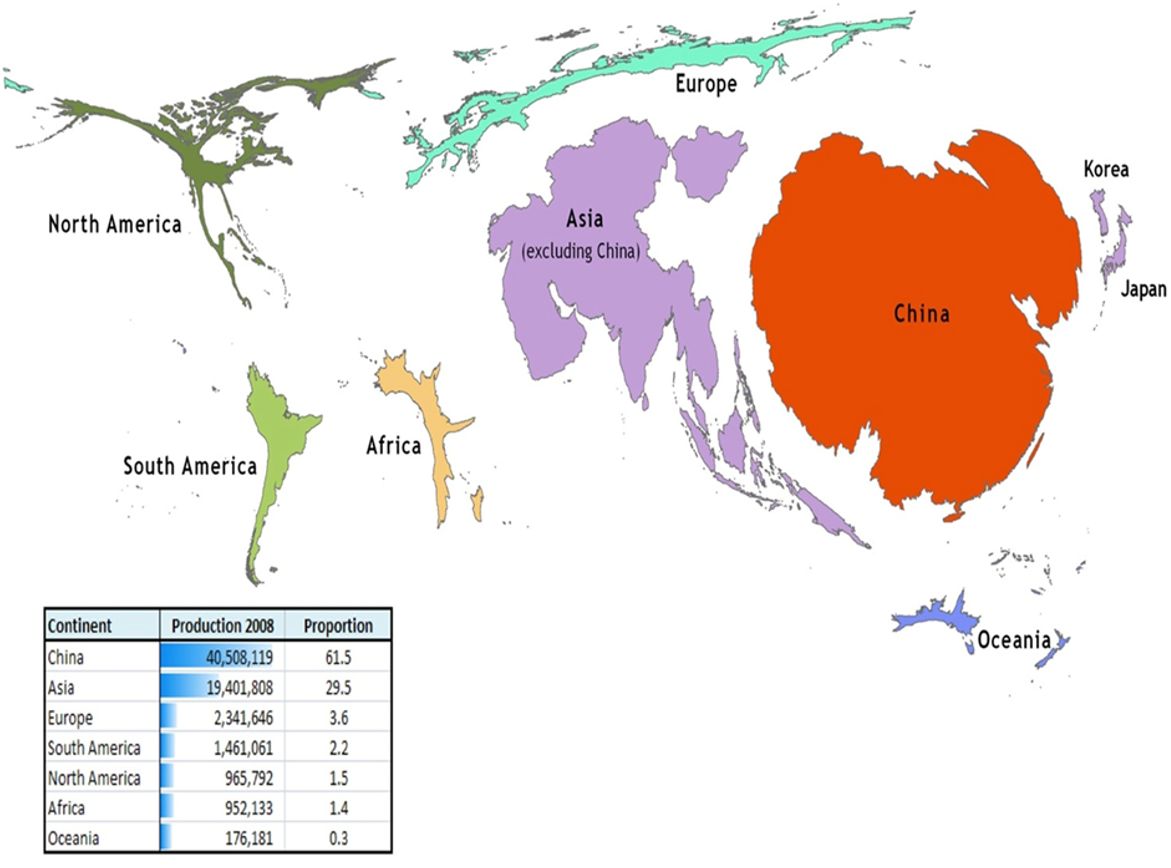

A few years ago, the estimated global aquaculture supply was around 80 million tonnes. At the moment, 10% of the global population is estimated to be involved in fishery and aquaculture value chains. A lot of money (roughly a trillion dollars) and jobs are involved in that. However, this is not equally spread around the world. Asia, and particularly China dominates aquaculture production and consumption.

Figure 7: Map of the globe with countries resized to represent aquaculture production output (2008 data) (Source: Hall et. al. 2011)

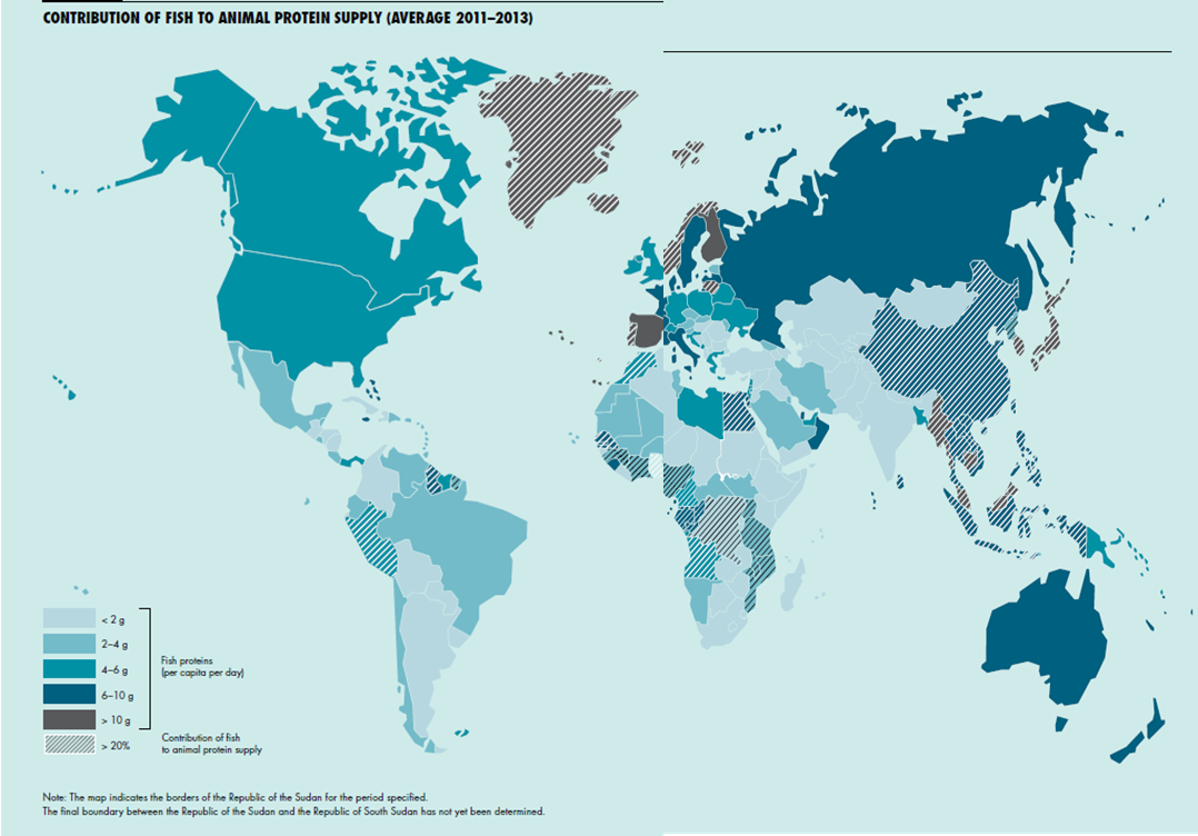

Figure 8: Map of the world with countries shaded to show the degree to which seafood contributes to total animal protein supply (source: FAO, 2016)

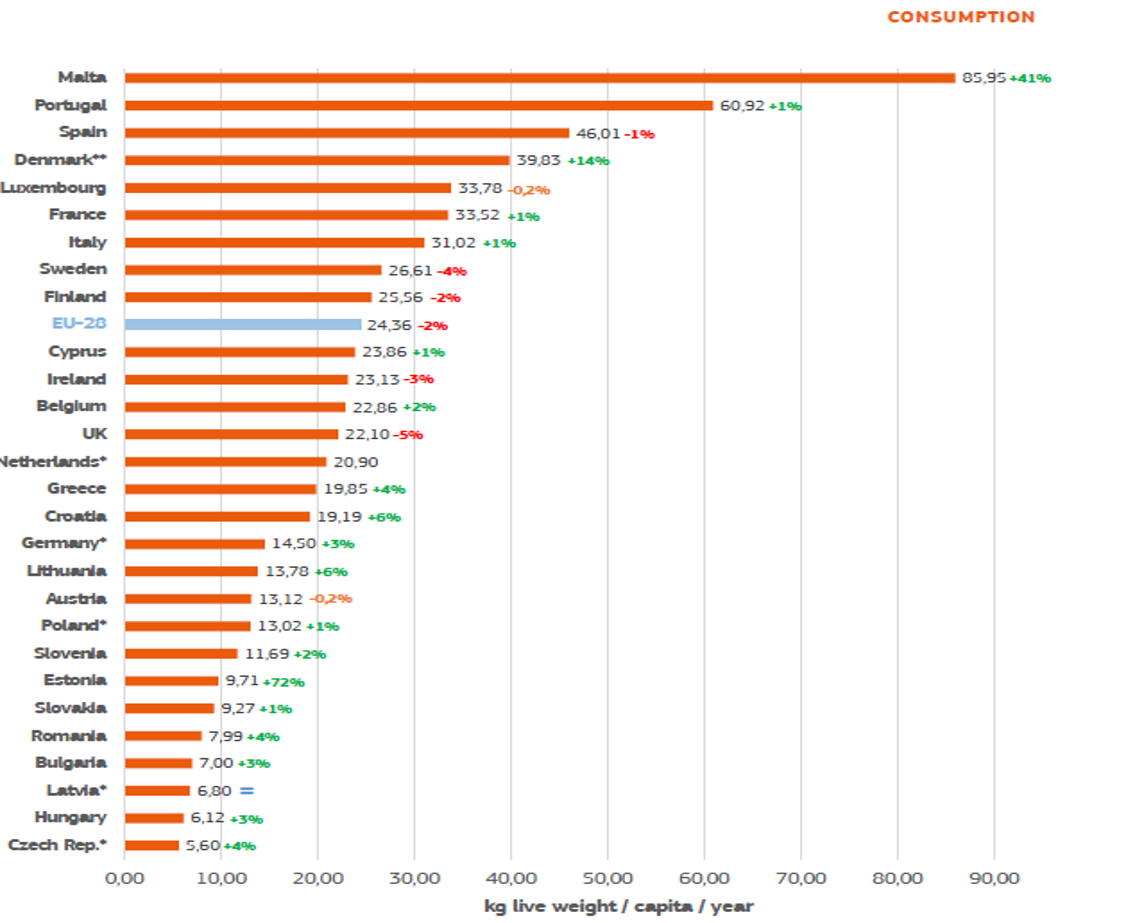

There are huge variations within Europe with

Malta reaching over 80 kilos and the Czech Republic less than 5 kilos.

Figure 9: Per capita consumption of seafood in European countries (source: EUMOFA, 2020)

What are some of the purchasing factors in the EU? What makes people want to buy and eat seafood? You would think that freshness and presentation would be at the top; however, purchasing power and willingness to pay are important. In some parts of the world, the origin, brand, and quality labels of a product are also important.

Figure 10: The importance of different seafood product attributes for UK consumers (source: Seafish, ©IGD 2019.

Exploring shopper behaviour when purchasing fresh fish and seafood: Category

benchmark report. IGD ShopperVista 2019)

Generally, seafood is seen as a luxury item. Convenience and propensity to try new products are also important when considering which supermarket shelves they will be on. Price is important in the seafood business, but what about nutritional security and how that is important, not just in filling stomachs but making sure people are well-nourished?

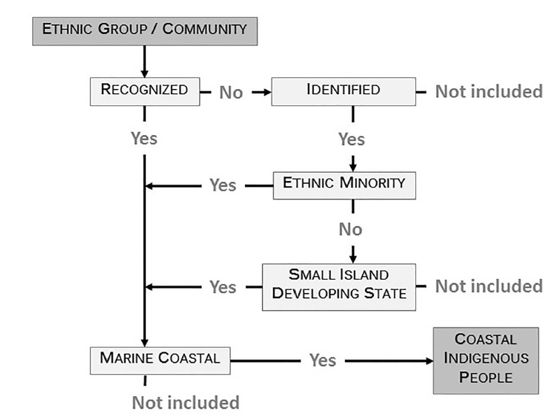

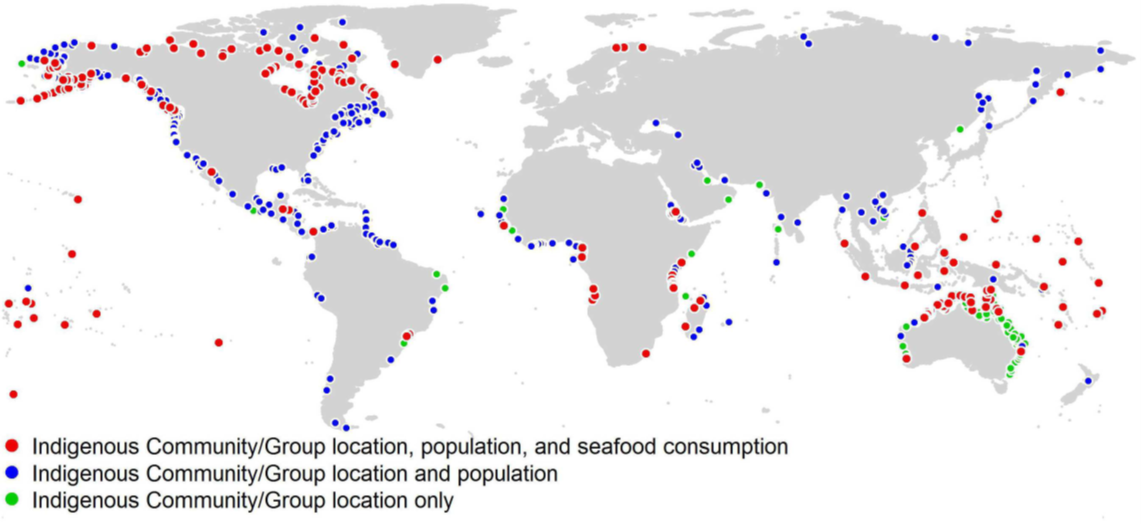

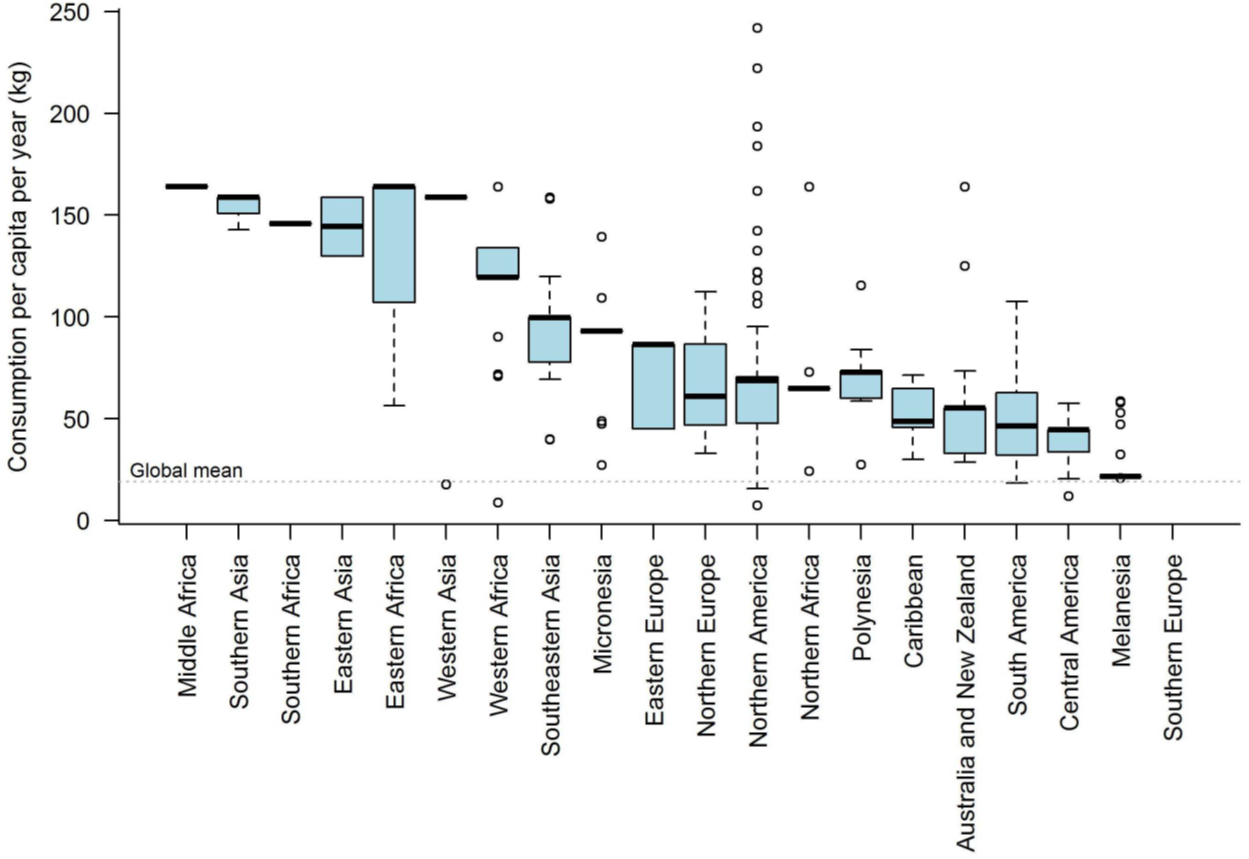

And of course, just as there are massive differences between countries in Europe, there are large differences within countries. Sometimes in terms of specific ethnic groups. Cisneros-Montemayor found that seafood is incredibly important to coastal people, with consumption per capita reaching well over 100 kilos. This is most likely linked to how, we as a species, developed where we were drawn to catching aquatic animals as they were easier to access than other types of animals and less large and frightening. Over time, these have become traditions in those areas. For example, West Bengal and Bangladesh are massive fish eaters and they take those habits with them when they move. The patterns we see in urban settings are often linked to immigrant communities.

Figure 11: Definition of "Coastal Indigenous People" study unit (source: Cisneros-Montemayor et. al. 2016)

Figure 12: Locations of coastal indigenous people included in the analysis (source: Cisneros-Montemayor et. al. 2016)

Figure 13: Consumption per capita for indigenous groups by global subregion (source: Cisneros-Montemayor et. al. 2016)

In the last 50 years, there's been an increase in the development of commercial aquaculture as overexploitation of natural stocks have led to the situation where supply can't meet the demand. Commercial aquaculture has developed the most rapidly in some Asian countries as they are becoming more urbanised, people are not self-provisioning, so they are dependent on supplies going through market chains.

In general, where it's worked and been successful is where governments have been supportive of private sector development. Farming is a private sector activity, and that's where you get innovation, development, and investment. For example, making sites suitable for aquaculture available and a competitive activity is important. This can be done in several ways. It can be by not having overly restrictive land-use regulations or providing services in so-called aquaculture parks; but generally, it's about making sure that aquaculture can compete with other forms of land and water use. With scale comes affordability and this is a huge factor in the countries where aquaculture is growing fastest. In general, the price of a farmed product has dropped in comparison with wild and with other forms of animal source food, so it's becoming a more affordable and conscious choice that makes it a regular food item.

The value chain has a multiplier effect on employment and the environment. For example, the import of feed ingredients requires the knowledge and expertise to turn raw ingredients into formulated diets that work efficiently in the animals of concern. Jobs are of various types through the value chain and we have to think not just about them being employment, but the quality and where it occurs through that value chain.

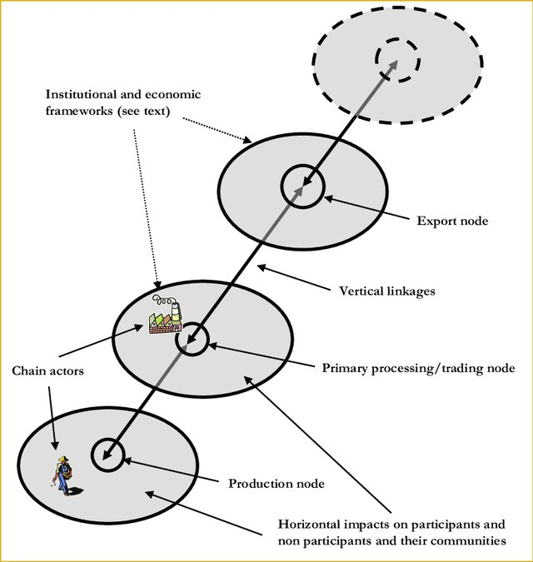

Figure 14: Illustration of nodes, actors and institutions and linkages in the value chain approach (Source: Bolwig et. al 2010, as reproduced in Nygaard & Hansen, 2015)

Is the employment for men and women? Is it for highly qualified people or less skilled people? Is it for younger or older people? Is it year-round or is it seasonal? Is it a type of intense activity where there is a large processing sector that needs lots of young women and men in the processing line? This is the way that we can think about how livelihoods are impacted by the development of these seafood value chains. This can lead to broader communities (spillover effects) of that economic activity around production or processing.

It is important to be aware that there are sometimes areas of negative impact in the value chain. For example, some Thai shrimp farms were linked through the purchase of marine ingredients that were produced on slave managed boats.

Figure 15: Newspaper headline on publication of a Seafood Watch report (Source: The Guardian, 23 Jan 2018. Photo by Rungroj Yongrit/EPA)

Figure 16: Newspaper headline about the investigation into labour practices in the Thai shrimp processing industry (Source: The Guardian, 14 Dec 2015. Photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP)

Figure 16: Newspaper headline about the investigation into labour practices in the Thai shrimp processing industry (Source: The Guardian, 14 Dec 2015. Photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP)

Video: Documentary from the Environmental Justice Foundation on human rights abuses in Thailand's seafood industry (2015)

The linkages between poor practices at one node go on and affect the reputation and the reliability elsewhere. What are the standards for each of those nodes? How can we make sure poor practice doesn't happen, how can we reduce levels of corruption, how can we protect employees, and how can we make sure you know slave labour and other human rights abuses are completely eradicated from seafood value chains? The supermarket buying the finished article has to be assured of the ethical value through that value chain. It's not easy as these are complicated value chains that stretch across the world. It isn't enough to go into an international marketplace and say you want to buy shrimp at this price. You have to say you want to buy shrimp with the assurance and traceability that they are produced without negative environmental and social impact.

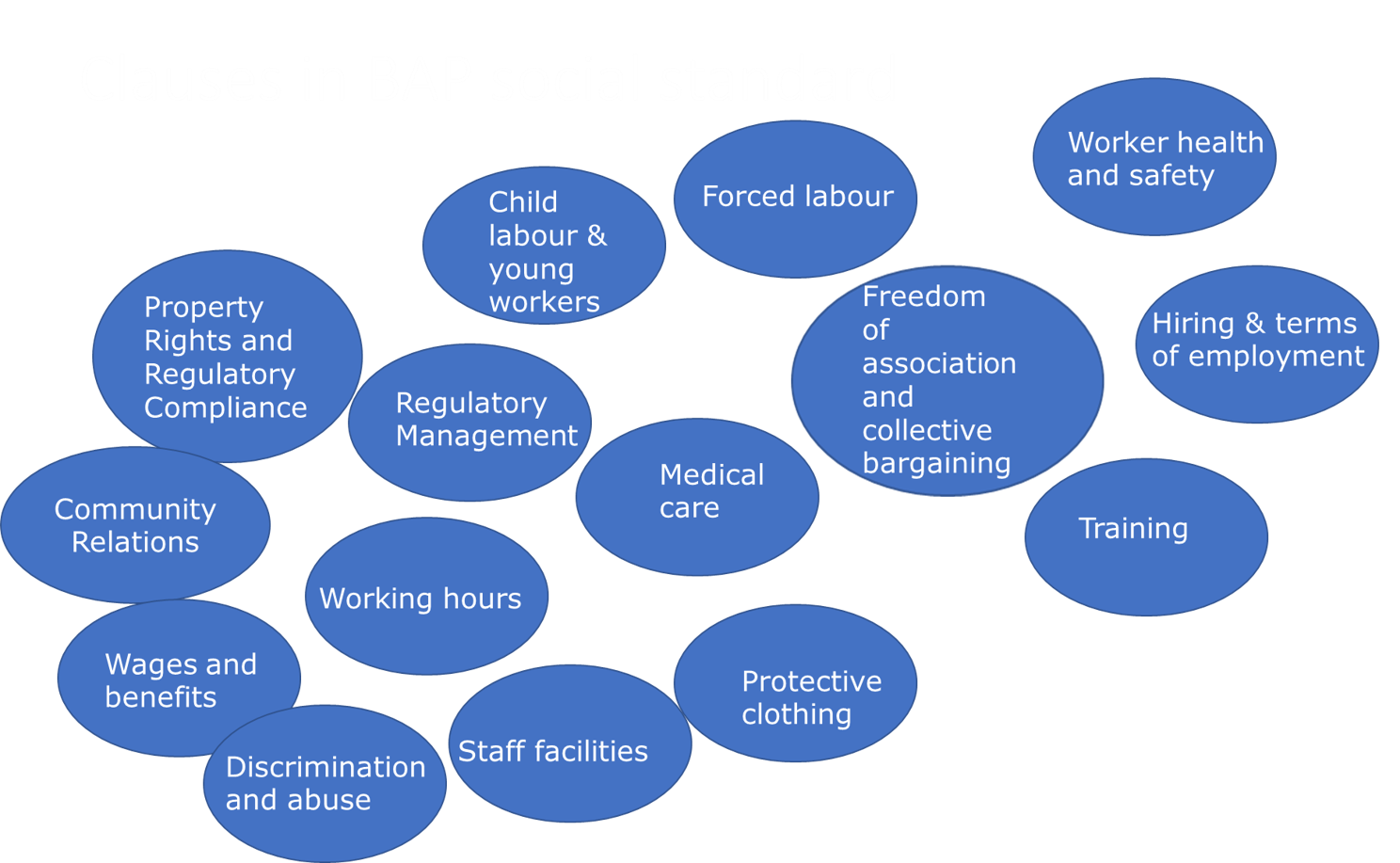

Seafood value chains need to be managed well so they are compliant with social standards, labour standards, and environmental standards. Farms of all types are dangerous places. Working below water is risky, and parts of the sector employ professional divers who are responsible for cage maintenance. The International Labour Organization exists, but the reality is that farms in rural areas of poorer countries do not do things by the book. The more oversights in general, the higher the costs.

Does this farming practice or processing plant adhere to some type of standard operating procedure? Who's going to check on it? How often and in what way? These are all key issues behind trying to make seafood value chains more transparent and give assurance to people through the chain that standards are being maintained, not just reached, but actually being maintained and even improved.

These are value chains that often depend on not highly paid people, and they become beacons for attracting migrant workers. How is that process managed because most countries have strict regulations on who can come into a country, on what basis, to do what and for how long? This fits in with making sure that there is no abuse in this system, that if migrants come to work on a sector of the seafood infrastructure that there's no forced labour or bad practices in it. Building that into standard operating procedures can be done for larger organisations but of course, a lot of it is much smaller enterprises that are more difficult to monitor, and this is where some of the issues remain. It's not solved just by having higher standards. Compliance is about what else is going on in that society as well.

Figure 17: Key headings in the BAP Social Standards (source: Developed from the Global Seafood Alliance Best Aquaculture Practices)