Socio-economic impacts

Professor David Little introduces social aspects of sustainability in the following presentation:

The use of terms to describe the societal dimensions of sustainability of food systems are varied but include socioeconomic-literally those that relate to a combination of social and economic factors. Specifically, this term has been used to differentiate groups of people based on their financial situation, or to denote the social status of an individual or group based on a combination of education, income, occupation. Comparisons between individuals within groups and even by individuals within households can allow key differences in wellbeing to be assessed, particularly useful over time, to inform the distribution of resources and development actions. For example the targeting of lower-income households within a community for food subsidies or disadvantaged individuals within families for dietary nutritional supplements. Typically individuals compare themselves with other family members, to other close groups (e.g friends and neighbours) but also with those in other locations, on both a national and international level (Check out this article (Gugushvili 2020) from a study in Europe). Perceptions and measures of changes in socioeconomic status may reflect access to food of varying quality, abundance and cost. For example, food frequency surveys can be used to categorise typical diets or track variations in nutrient intake for people of different socioeconomic groups

In contrast, the term social economics focuses on the relationship between social behaviour and economics and challenges the concept that food choices are only linked to individual preferences and available income, but rather that they are also shaped by social and cultural factors. There have been two major directions of analysis. The first one draws on microeconomic tools applied to human behaviours that integrate ‘social environments’ and has been used to explain social outcomes around crime, family issues etc.

Social economics, a branch of economics, has worked in areas outside of mainstream economics such as area of the effects of the environment and ecology on consumption and affluence. The differences in food purchasing and consumption behaviours of different socioeconomic classes or groups is one example. Rising affluence has been the major driver of unsustainable resource use and existing societies, economies and culture all promote unsustainable consumption of which dietary trends are a core feature (Wiedmann et. al. 2020).

Animal-source foods (meat dairy, seafood) are particularly resource-intensive and environmentally impactful but also desired with rising affluence and considered a key, nutrient-dense part of healthy diets by most nutritionists.

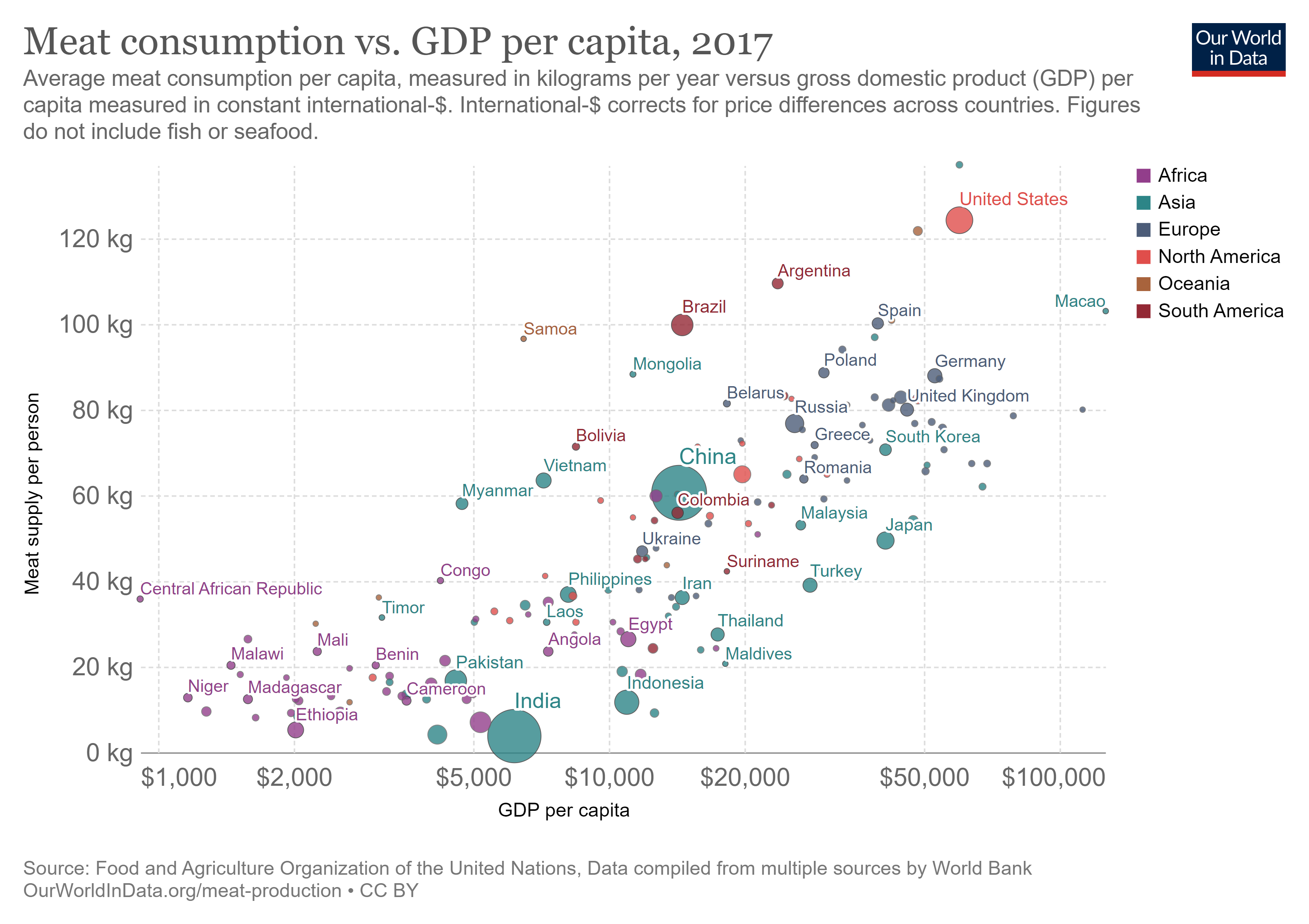

On a global level, there is a linear relationship between meat consumption and national wealth (as indicated by GDP).

Figure 12. A broadly linear relationship can be seen between individual meat consumption and national wealth (GDP). (source. Our World in Data)

In general poorer countries have much lower per capita meat consumption than richer countries.

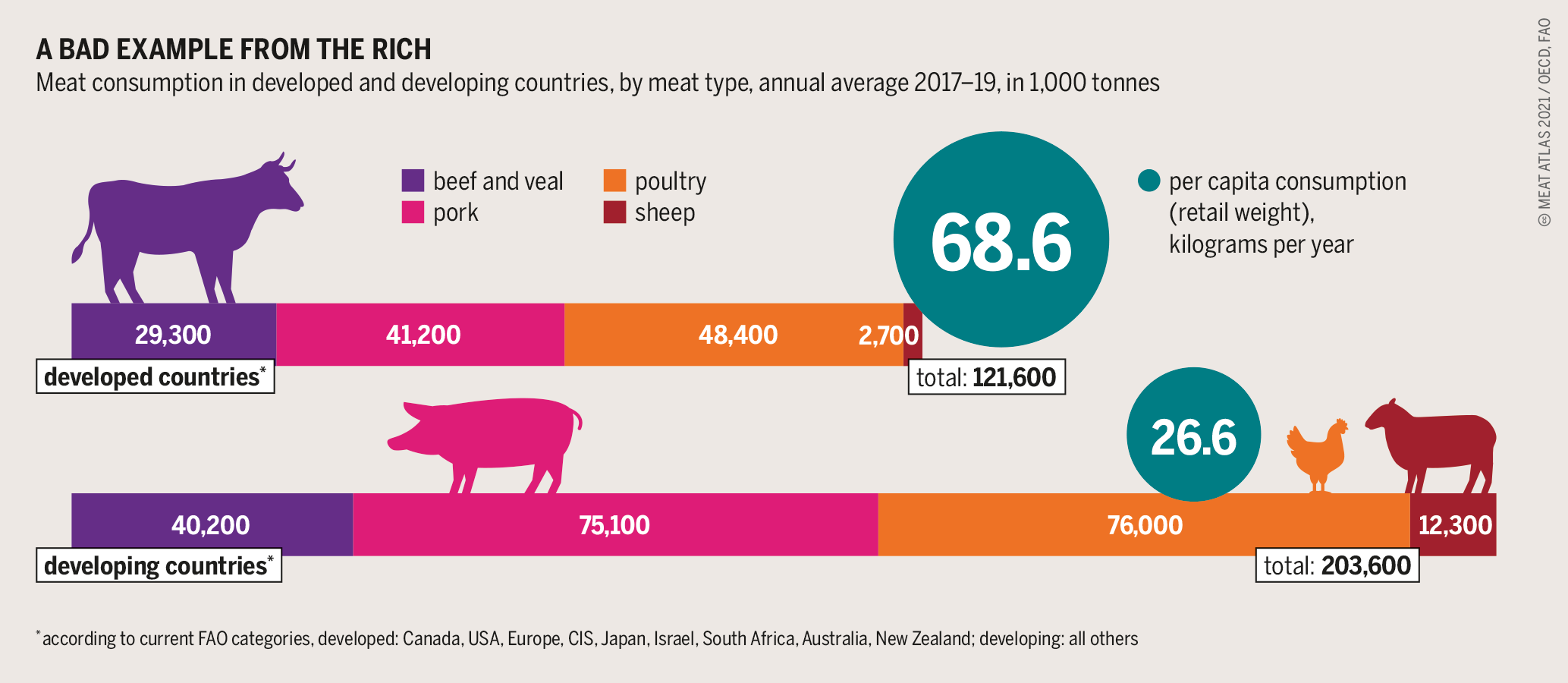

Figure 13. Comparison in per capita meat consumption between developed and developing countries (source: Tostado, 2021)

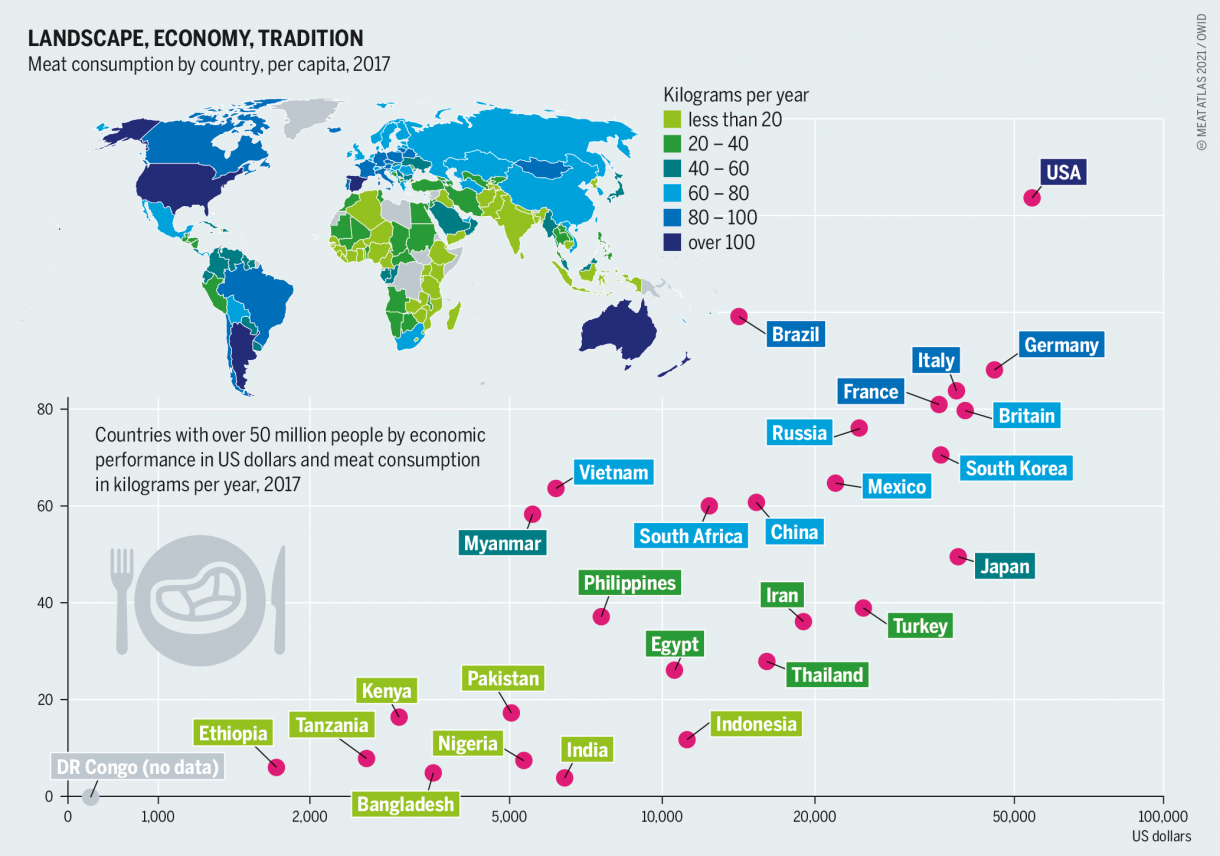

Figure 14. Meat consumption in relation to national GDP (source: Tostado, 2021)

The linkage between resource-intensive diets that lead to poor human health and environmental outcomes and a need to move towards plant-based diets has been widely promoted, notably at a global scale in the EAT-Lancet commission. Such a vision

however has attracted significant criticism on the basis of its social and economic factors but also for the case it makes regarding optimising nutrition for different groups of consumers, which has in turn been critiqued for its lack of recognition

of differential nutritional requirements of specific demographic groups such as children (Bäck et. al. 2021) and local context (see also Verkerk, 2019).

The sufficiency of its nutritional recommendations have also been questioned, its independence and adherence to good nutritional science (Nutrition Coalition, 2019). It has also clearly galvanised a sharp and ongoing response from vested interests involved in meat production (Garcia et. al. 2019).

Perhaps most critically it has also been challenged on the basis of its low affordability by the World’s poor; one study (Hirvonen et al, 2020), estimated that the cost of an EAT–Lancet diet exceeded household per capita income for more than 1.5 billion people.

Figure 15. Cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet in 2011 international dollars by country income levels and major regions (source: Hirvonen et al, 2020)

See also: Willett et. al. (2019)