Water in meteorites

When the mineralogy and chemical composition of martian meteorites were analysed, there was evidence of traces of water. To understand the importance of this, we need to consider how these rocks formed.

Firstly, when these rocks crystallised from molten rock, they may have trapped water within their crystal structure. Since this was in very low amounts, they probably formed in water-poor conditions. Secondly, these rocks and their constituent minerals might have been exposed to liquid water (or gases) that may have weathered, or altered, them into new minerals. When certain minerals in martian meteorites were studied closely, some were found to be hydrous, i.e., they contained water or hydroxyl ions (OH−) in their molecular structure.

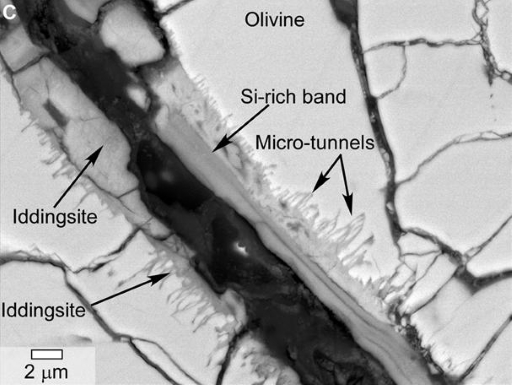

Examples of hydrated minerals include: the iron hydroxide goethite; evaporite minerals (precipitated when water evaporates) such as gypsum; opaline silica, and phyllosilicates (which are also known as clay minerals, such as those found by the Viking landers). Collectively these are known as alteration (or secondary) minerals. In martian meteorites, most of these alteration minerals are so small that they can only be seen using high magnification microscopes, such as a scanning electron microscope (SEM). An example of a high resolution image of a martian meteorite, taken using an SEM, is shown in Figure 19.

Not all minerals incorporate water in their structure, but some of them require water to be formed. You will be familiar with rust that appears on metal surfaces when they are exposed to water. Rust is iron oxide (haematite) or iron hydroxide (goethite), and both are found in martian meteorites, often associated with other hydrous minerals.

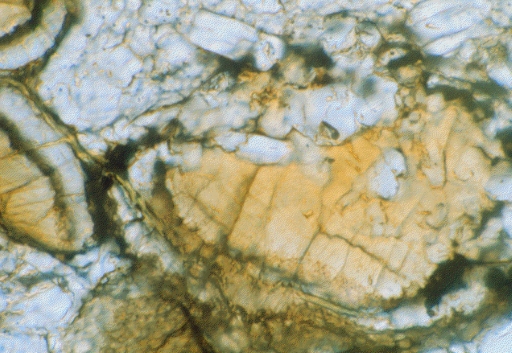

You may also be familiar with limescale, which is the deposit left behind when water dries up in bathtubs and sinks. This is made predominantly of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), and carbonates have also been found in martian meteorites (Figure 20). Indeed, the carbonates present in one particular martian meteorite – ALH 84001 – became the focus of huge scientific attention when it was argued that they contained organic, fossilised remnants of ancient martian bacteria.

To date, numerous studies have shown that the organic material was likely to be contamination from Earth and that the carbonates can be formed by processes that do not require life to be present. Despite this, the controversy around ALH 84001 came at a time when interest in Mars was experiencing a renaissance, with the 1990s seeing the launch of several missions to the red planet. The search for water on the planet was back on!