4.3 Cellular changes

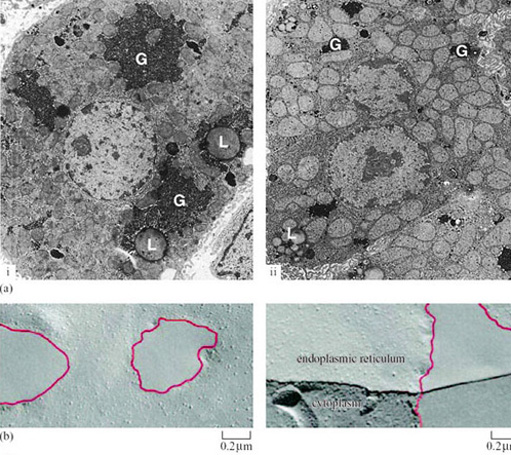

Hibernation can result in the deposition of fat in adipose tissue. In tissues of finite size which are important sources of energy and sites for fuel metabolism, changes in cell structure (redistribution of organelles involved in energy metabolism and protein synthesis) are the most likely adaptation to a state of torpor. Liver hepatocytes of the hibernating dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius), are visibly different from those of arousing and euthermic dormice when viewed in thin section with a microscope (Figure 26a(i) and (ii)) (Maletesta et al., 2002).

Question 12

Can you see evidence of these differences in Figure 26a?

Answer

There is a substantial reduction in the cross-sectional area of both the whole cells and the cytoplasm in the hibernating dormice. The number of granular glycogen deposits is reduced which suggests that carbohydrate metabolism is reduced. The Golgi apparatus shrinks dramatically, which indicates that reductions in protein and lipid synthesis as well as carbohydrate metabolism have occurred.

Glycogen does not reappear in the cell for several hours after arousal. However, the whole cells and the cytoplasm increase significantly in size and start to resemble those of euthermic animals. The reverse changes are true for lipid storage in the cell, with the proportional cross-sectional area occupied by lipid droplets being significantly increased in early hibernation, reduced in deep hibernation and almost disappearing during arousal. Changes in the structure of organelle membranes in neurons from the brain of hibernating hypothermic ground squirrels are also visible when viewed with an electron microscope. Membrane lipids and proteins coalesce to leave patches free of protein (Figure 26b) (Azzam et al., 2000). These detailed observations provide clear indications that fundamental restructuring of lipid bilayers can occur as an adaptation to torpor. The reasons for the changes are not fully understood, but presumably they give some protection from cold-damage and permit rapid recovery of cells from temperatures close to zero. The survival of cells is also the subject of molecular adaptations as we will see below.