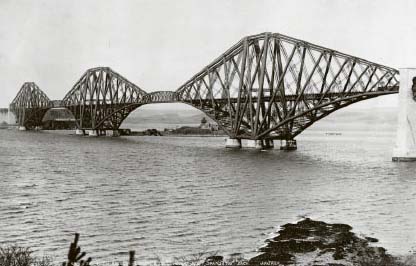

6.2 Forth Bridge

When the Forth was eventually bridged in 1890 it marked a new dimension in bridge construction. The main crossing is 5330 feet long and has a headroom above high water of fully 157 feet. It consists of three huge double cantilevers fabricated from steel with a maximum height above high water of 361 feet. The bridge contains 58 000 tons of steel, of which 4200 tons are just rivets. The steelwork has an external area of 145 acres and it is a full-time job for a gang of 29 painters to protect the structure against corrosion. The Forth Bridge was as massive as the old Tay Bridge was slender; its designer Sir Benjamin Baker was taking no chances (Figure 50).

Baker had inspected the ruins of the Tay Bridge and gave evidence to the Tay Bridge enquiry. He was one of the few experts called who drew attention to the absent fallen piers. He could not express an opinion about the workmanship of the key evidence still lying in the estuary, but did agree the tie bars were a weak link in the load path, especially the cast-iron lugs.

Overall he felt the wind was not the cause of failure, but rather the poor design of the structure. He pointed out that the windows of both signal boxes were intact, showing the wind pressure the night of the accident were not excessive. He had examined every exposed structure in the vicinity of the fallen bridge, and concluded that the wind pressure could not have exceeded 15 pounds per square foot. He, and the court, also noted the large number of chimneys in Dundee town that had not been affected during the storm (Figure 21).

His direct experience of the failure, and public anger expressed at the time of the disaster, clearly influenced his design of the Forth Bridge. Bouch had actually been working on a design to cross the Forth: it was to be a suspension bridge with two gigantic towers 600 feet high at either end. The project was cancelled after the disaster, and Baker's new concept of a cantilever structure adopted instead.

As a direct result of the Tay Bridge disaster, Parliament imposed many restrictions on the new proposal, instructing the BoT to inspect directly at every stage of construction, reporting four times a year until the bridge was finished. They also stipulated that the bridge must

… gain the confidence of the public and enjoy a reputation of being not only the biggest and strongest, but also the stiffest in the world.

The latter was to be achieved both vertically under live rolling loads but also laterally from wind loading. Only the best materials were to be used, the steel meeting Lloyd's requirements for steel used in shipbuilding. Such considerations led to a bridge being at least twice as secure as it needed to be, and stands to this day, despite the onerous and never-ending duty of painting the exposed steelwork.