Telescopes and Astronomy Across the Electromagnetic Spectrum

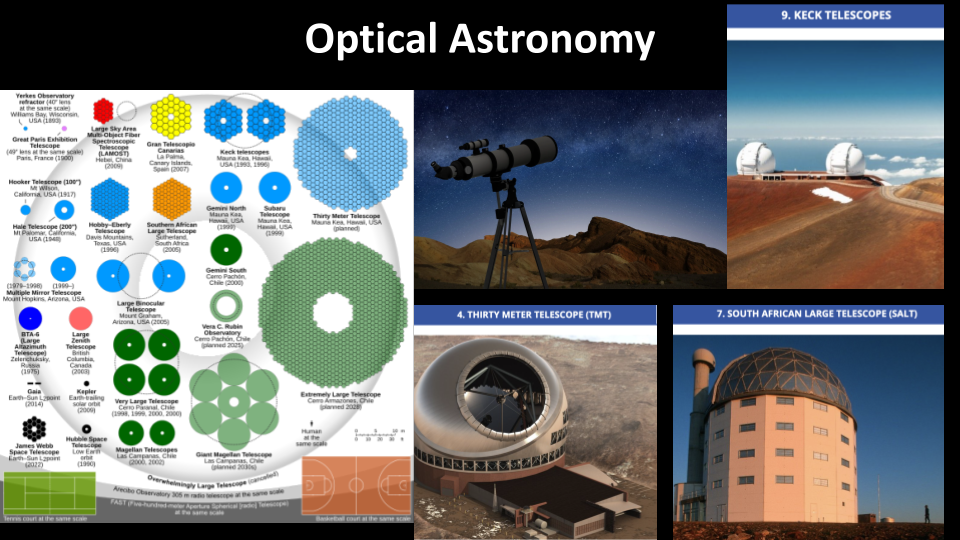

The telescope is the astronomer’s most important tool, an extension of the human eye into realms we could never otherwise perceive. The first telescopes, built in the early 17th century, used lenses to bend and focus light, revealing mountains on the Moon and moons orbiting Jupiter. Today, telescopes use both lenses and mirrors, often so large they must be housed in domes or arrays across mountains and deserts.

A telescope’s power lies in two qualities: resolution, its ability to reveal fine details, and sensitivity, its ability to detect faint objects. Modern telescopes also employ spectroscopes and cameras, splitting starlight into spectra. These spectra act as cosmic barcodes: from a star’s light we can measure its chemical composition, surface temperature, motion, and even detect the fingerprints of atmospheres on distant exoplanets.

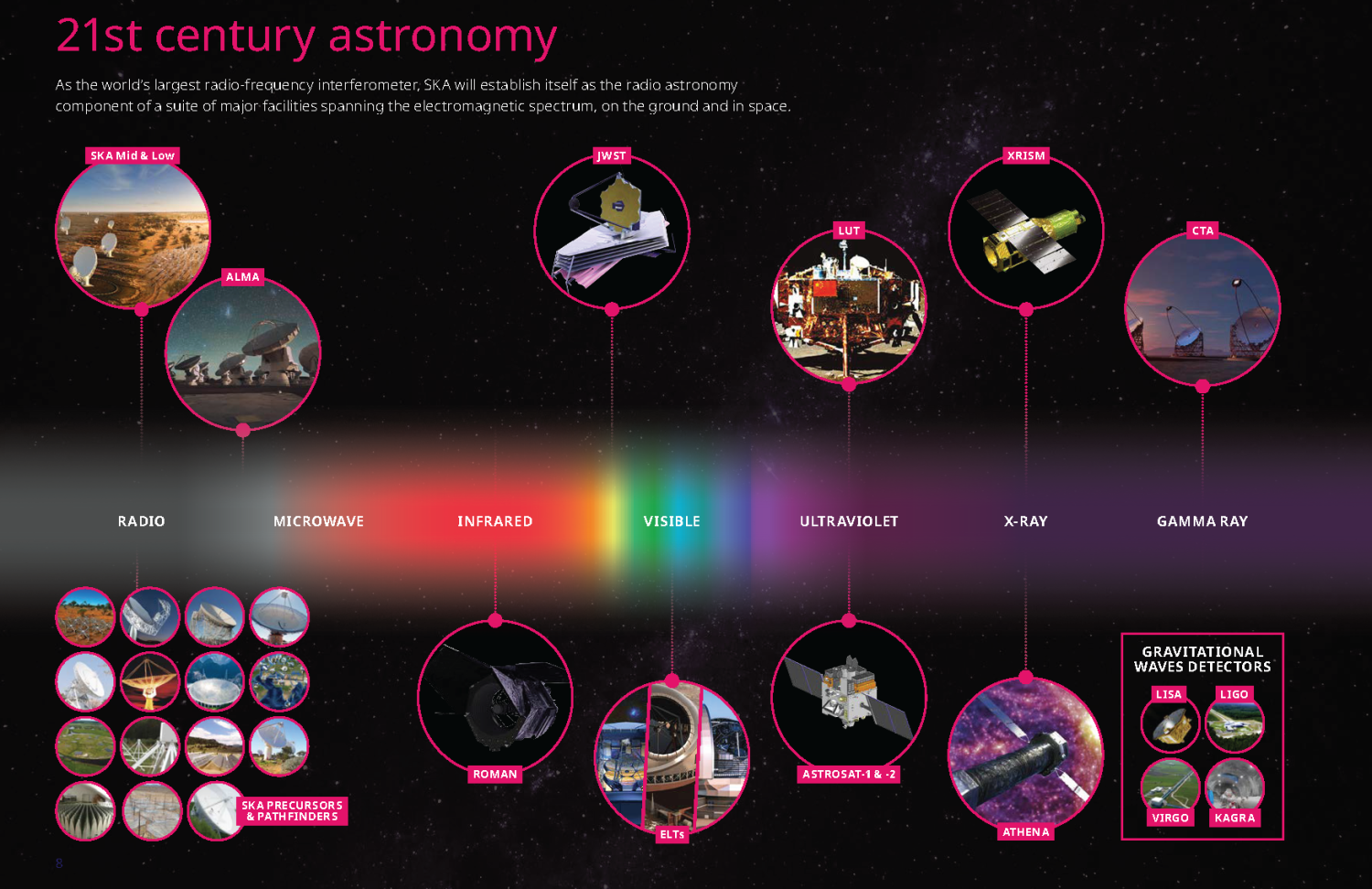

Astronomy throughout the spectrum (Source: SKAO)

Telescopes are no longer limited to visible light. Across the electromagnetic spectrum, specialised instruments reveal hidden universes.

-

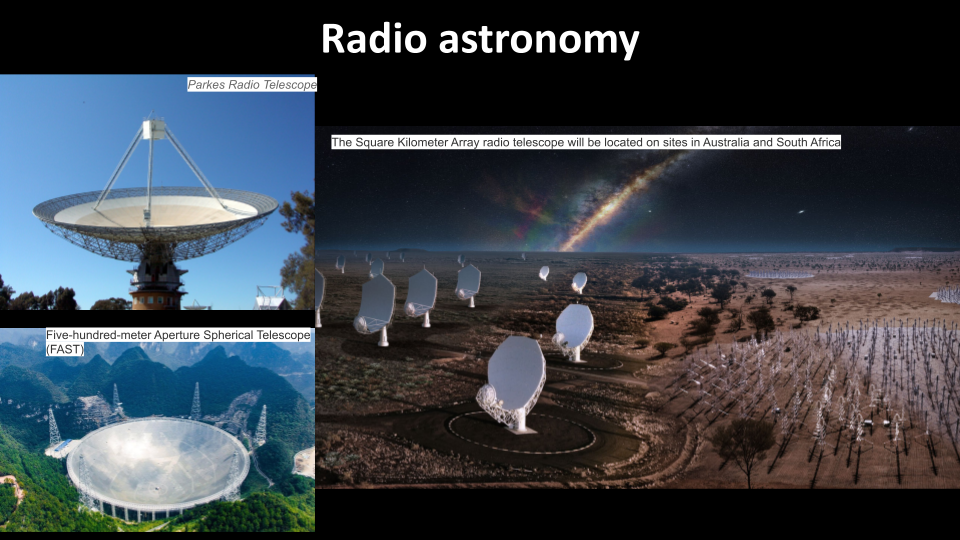

Radio telescopes, whether single dishes like Parkes or vast arrays like MeerKAT, detect long-wavelength signals. They can operate day or night, penetrate dust clouds, and map structures billions of light-years away.

-

Infrared telescopes, like the James Webb Space Telescope, see the heat of cool stars and planets, and peer into the dusty nurseries where new stars are born.

-

Ultraviolet telescopes study hot, young stars.

-

X-ray telescopes, such as Chandra, catch the high-energy light from black holes and neutron stars.

-

Gamma-ray telescopes, like Fermi, detect the most energetic and fleeting explosions in the cosmos.

Examples of different kinds of optical telescopes.

Examples of different kinds of radio telescopes

Some telescopes stand alone, but others are built as arrays, combining signals from many dishes or mirrors to act as a single, powerful eye on the sky.

Observing from Earth has its challenges. Clouds and weather can block visible light, while light pollution from cities drowns out faint stars. This is why astronomers often place observatories on remote mountains, deserts, or even in space. Above the atmosphere, telescopes avoid distortion and can capture radiation like X-rays or gamma rays that never reach the ground.

By collecting, focusing, and analysing light across all wavelengths, telescopes let us decode the messages written in starlight. They extend our vision from the nearby planets to the edge of the observable universe, revealing a cosmos richer and more complex than we ever imagined.