2.2 Receptor specificity

Binding of an extracellular signal to its receptor involves the same type of interactions as those between an enzyme and its substrate. Receptor specificity depends on the binding affinity between the ligand and the binding site on the receptor. The dissociation constant (KD) describes the affinity between receptors and their ligands.

Proteins can be thought of as consisting of various domains, and the different combinations of structural motifs in the extracellular regions of receptors will confer the specificity of a receptor for its ligand. Ligand binding may involve multiple sites of contact between the ligand and different domains of the receptor. It is possible that some interactions between the ligand and its receptor may be important for binding, whereas others may be necessary for signal transfer. An example of a ligand that binds to a 7TM receptor is C5a, a chemoattractant cytokine (called a ‘chemokine’). The interaction is an association of the C5a N-terminus with a pocket within the receptor, involving its extracellular loops 2 and 3, and the N-terminus. This interaction is not in itself sufficient for receptor activation. For this to occur, the C-terminus of C5a must bind to other sites in the bundle formed by the receptor's seven α-helical membrane-spanning segments.

Ligands are classified as either receptor agonists or antagonists, depending on the outcome of interactions between ligand and receptor. Agonists usually work by binding to the ligand binding site and promoting its active conformation. Antagonists bind to the receptor, but do not promote the switch to the active conformation. In addition, it is not always the case that one ligand binds specifically and uniquely to one particular receptor. A single receptor may be able to bind several different ligands, and a single ligand may be able to bind to several receptors.

Here we shall describe two clinically important and well-known examples of receptor–ligand interactions – acetylcholine, a ligand for two structurally different classes of receptors, and adrenalin, which, together with noradrenalin, binds to a number of closely related receptors. (Adrenaline and noradrenaline are also known as epinephrine and norepinephrine, respectively.) We shall return to these receptor signalling pathways throughout the rest of the chapter to illustrate further general principles of signal transduction.

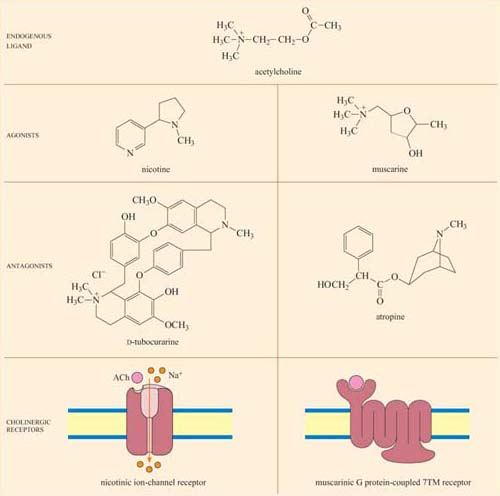

Acetylcholine (ACh) is a neurotransmitter that is released from neuron presynaptic terminals. At the neuromuscular junction, neuron terminals contact a specialized region of skeletal muscle (called the ‘motor end-plate’), where acetylcholine functions as a primary neurotransmitter by stimulating muscle contraction (see Figure 7). In addition, acetylcholine also acts as a neurotransmitter in the heart, where its release slows down the contraction rate. However, ACh receptors (sometimes collectively termed ‘cholinergic receptors’) are structurally and functionally distinct in these two different tissues, and consequently have completely different sets of agonists and antagonists (in both tissues, ACh receptors normally bind to acetylcholine, their endogenous ligand; Figure 18).

In skeletal muscle, the ACh receptors are ion-channel receptors (Figure 18 and Section 2.3), and are also known as nicotinic receptors. The skeletal muscle subtype of the nicotinic receptor can bind two naturally occurring powerful toxins, the polypeptide α -bungarotoxin (found in the venom of the krait snake) and the alkaloid tubocurarine (found in curare, a poison extracted from the bark of certain trees in South America, and used in the arrows of some tribes). These toxins act as antagonists, and bind reversibly, but with higher affinity to the nicotinic receptor than acetylcholine itself. For example, the KD of α -bungarotoxin is 10−12 to 10−9 mol 1−1, whereas acetylcholine binds with relatively moderate affinity to nicotinic receptors; its KD is 10−7 mol 1−1. As a result, they prevent the action of ACh by binding to and blocking its receptor without activating it, resulting in paralysis and eventually death.

Cardiac muscle contains the other type of ACh receptor, which is a G protein-coupled 7TM receptor (GPCR). This, and the several related subtypes expressed in other neural locations, are usually called muscarinic receptors. Atropine is a naturally occurring antagonist of muscarinic receptors, and is derived from the berries of deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna (so called because extracts of it were applied to the eyes by women in the Renaissance period, which resulted in a ‘doe-eyed’ beauty). One of the downstream consequences of binding of acetylcholine to muscarinic receptors in cardiac muscle cells is the opening of K+ion channels, which causes membrane hyperpolarization and a decrease in the heart's contraction rate.

Because the muscarinic and nicotinic receptors are not structurally related, there is no overlap between their major agonists and antagonists; nicotine, α-bungarotoxin and tubocurarine have no effect on muscarinic receptors, whereas muscarine and atropine have no effect on nicotinic receptors. How, then, can acetylcholine be a common agonist and bind to two completely different groups of receptors, if their other agonists and antagonists are restricted to binding to just one type each? The answer lies in the flexibility of the acetylcholine molecule. Most of the agonists and antagonists have relatively rigid ring structures, whereas acetylcholine is able to adopt different conformations (Figure 18, top), which may help it adjust to the different binding sites in the two receptors.

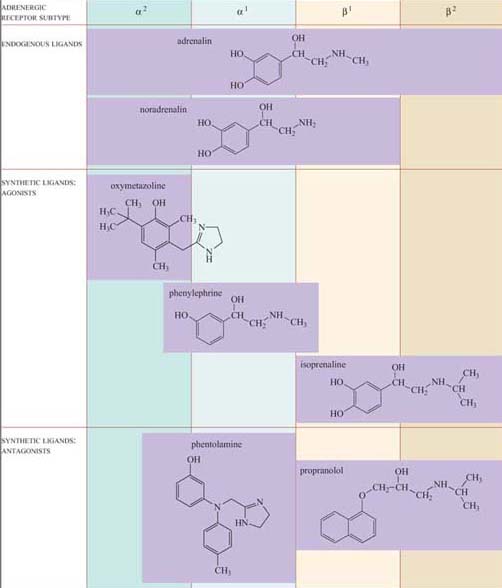

Adrenalin is the classic ‘fight or flight’ hormone, having effects on multiple tissues that help put together an appropriate coordinated response to a situation of danger. Actions as varied as increased heart rate, dilation of relevant blood vessels (especially those in skeletal muscle) and constriction of other blood vessels (especially in the skin and digestive tract), and mobilization of metabolic fuels (such as glycogen in liver and skeletal muscle, and stored fat in adipose tissue) are all part of this response.

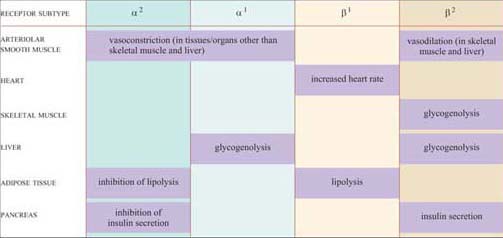

These effects are mediated by two classes of structurally related GPCRs, the α and β adrenergic receptors, which have the subtypes α1 and α2, and β1, β2 and β3, each with different tissue distributions (Figure 19). Figure 20 shows the range of effects of α and β adrenergic receptors in various tissues and organs.

For example, the smooth muscle surrounding arteries in the digestive tract contains predominantly α receptors, which mediate vasoconstriction, and the smooth muscle surrounding arteries in skeletal muscle contain predominantly β receptors, which mediate vasodilation. Note also that the β2 adrenergic receptor increases insulin secretion by pancreatic cells, whereas the α2 adrenergic receptor reduces it.

The classification of adrenergic receptors is based on their interactions with various synthetic agonists and antagonists, which probably reflects the receptor structures. In the simplest example, both α receptors are stimulated by the agonist phenylephrine, and β receptors are exclusively stimulated by the agonist isoprenaline. On the other hand, phentolamine acts as an antagonist of α receptors, whereas propanolol acts as an antagonist of β receptors. Adrenalin itself, of course, can bind all the receptor subtypes, but the structurally related noradrenalin (which is also released into the circulation), has a more restricted binding profile and much more limited effects.