2 Giving feedback

When giving feedback on students’ writing, focus on just one or two aspects at a time. This will ensure they do not become dispirited by over-correction or overwhelmed by too much feedback. When giving feedback on a first draft, it is important to praise the student’s efforts at composition. Did the student have a good idea for a story? Did the student write interesting dialogue? Did the student remember to write the main points of a report? Did the student make a good effort to write in English?

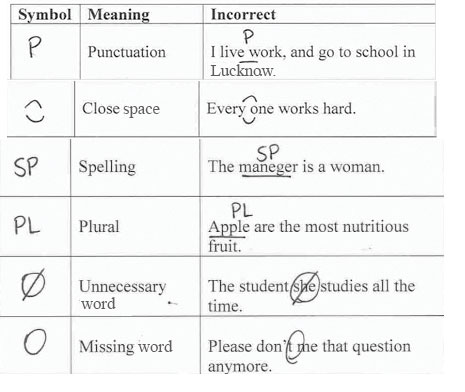

For feedback on transcription, mark their drafts with symbols and discuss with the whole class what these mean. Examples are shown in Figure 3.

Even if your class is large, it is important that you give individual feedback to all students. There is no single way of giving feedback or remarks. What needs to be kept in mind is that feedback should create a positive attitude towards writing. In the next case study, a teacher must decide how to give feedback on a student’s writing.

See Resource 1, ‘Monitoring and feedback’, to learn more about the methods to evaluate and record student progress.

Case Study 2: Ms Afreen assesses dictation

Ms Afreen teaches in a government school where all the students are first-generation school goers.

I gave students dictation from the textbook. When the students handed me their work, I reviewed it and saw that a ten-year-old girl had spelled the words ‘pencil’, ‘rubber’ and ‘boxes’ as follows:

- pensl

- rubr

- bokss.

My first reaction was to correct these mistakes. But I could see that the girl knew the initial sounds of English words. She recognised consonant sounds, and she knew that some words began with a capital letter. She was not yet distinguishing English vowel sounds in between consonants. I can see that she was using her oral knowledge of English to make a good attempt at spelling, although this was not always correct in writing, as can be seen from the use of ‘k’ for ‘x’ and ‘s’ for ‘c’. I decided she was making a good attempt at writing based on her current understanding of English letters and sounds.

I praised her attempts. But I also told her to read her writing more carefully and to check her spelling using a dictionary. I encouraged her to read more, because the more she reads in English, the better her English spelling will be.

I do not ignore errors in writing, and I give students feedback and correction. But I try to see how their mistakes give me clues about their thinking process and developmental level. Their mistakes show me what I need to plan next.

Activity 2: Errors and assessment

Errors in writing can be categorised broadly as:

- ‘silly mistakes’ or slips that students can correct on their own once they have been pointed out to them

- ‘misunderstandings’ that students cannot correct themselves and that need to be explained by teachers

- ‘attempts’ where students try out something but make mistakes because they do not yet have the required language skill or knowledge.

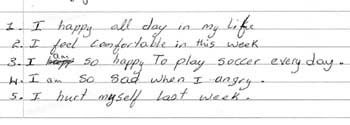

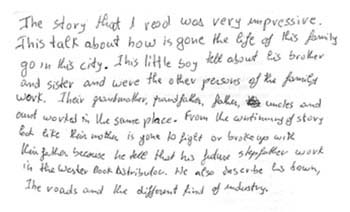

Look at two pieces of writing by students (Figures 4 and 5). Do they show evidence of ‘silly mistakes’, ‘misunderstandings’ or ‘attempts’? How you would evaluate the writing based on the concepts of ‘composition’ (the author) and ‘transcription’ (the secretary) that you read about at the beginning of this unit? What would you say to each student, to give them encouraging feedback? Talk about these examples with other teachers in your school and compare your ideas for evaluation and feedback.

When students speak and write in English they sometimes miss out English words if their home language does not use these words, like articles such as ‘a’, ‘the’ or ‘an’. Make this an opportunity to talk to students about the different structures of English compared to other languages.

People who are multilingual often mix languages in their speaking and in their writing – this is common everywhere in the world. You can make this tendency visible to students by inviting those who speak different dialects or languages at home to talk about a topic in their home language, or to write in their home language and read it out or display it to the class. You need to be careful in not to comment or to let other students pass comments. The objective must be to let students see for themselves that mixing languages is natural, and the occasional use of English is like using any other language they already know. Activities that bring students’ home languages into the English classroom will go a long way in helping to shed their inhibitions about speaking in English, and also celebrate the rich multilingualism of our country.

Video: Monitoring and giving feedback |

1 Composition and transcription