1 Using games for developing number sense

Pause for thought Think back to when you were a child. Did you learn anything about numbers outside of school? For example, you might have learned to count prior to attending school, or you might have come to know about money, age or sharing things equally from your life outside of school. How did such learning happen? |

Playing games is something children do from an early age. It is generally accepted that playing games stimulates the development of social interaction, logical and strategic thinking, sometimes competitiveness, or at other times teamwork and togetherness.

Games can give a sense of suspense, joy, frustration and fun. Research literature has shown that using games in teaching mathematics leads to an improved attitude towards mathematics, enhanced motivation and support for the development of children’s problem solving abilities (Ernest, 1986; Sullivan et al., 2009; Bragg, 2012). It is argued that the mathematical discussions that happen while playing mathematical games leads to the development of mathematical understanding (Skemp, 1993).

This unit gives examples of some tried and tested number games to help develop the number sense of students. It will also discuss how to spot good number games and learn to identify the learning opportunities the games can offer for students.

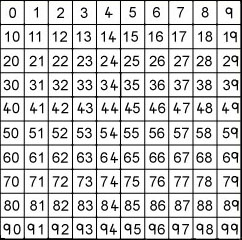

The first activity is an example of a game that helps to develop the understanding of number relationships. It uses a mathematical tool the students are already familiar with: the ‘hundred square’. Many such games are freely available in books and on the internet. The activities in this unit come from NRICH, a free mathematical resources website that is part of the University of Cambridge’s (UK) Millennium Mathematics Project.

Before attempting to use the activities in this unit with your students, it would be a good idea to complete all, or at least part, of the activities yourself. It would be even better if you could try them out with a colleague as that will help you when you reflect on the experience. Trying them for yourself will mean you get insights into a learner’s experiences which can, in turn, influence your teaching and your experiences as a teacher.

Activity 1: What do you need?

For this activity, students work in pairs or small groups. You can use Resource 2, ‘Managing groupwork’, to help you prepare for the activity.

Give students a printout or copy of a hundred square (Figure 1), or make them use one they already have in their books. Make sure they can all see the hundred square. It is also important not to tell them how to go about doing this task but to let them discover it for themselves so they have to think about strategies. This also keeps up the suspense.

Part 1: Deciding on what you need to know

Write the following on the blackboard:

Eight clues

- The number is greater than 9.

- The number is not a multiple of 10.

- The number is a multiple of 7.

- The number is odd.

- The number is not a multiple of 11.

- The number is less than 200.

- Its ones digit is larger than its tens digit.

- Its tens digit is odd.

Tell the students the following:

I have got a number in my mind that is on the hundred square but I am not going to tell you what it is. However, you can ask me four of the eight clues that are written on the blackboard and I will answer with yes or no.

There is something else I need to tell you: four of the given clues are true but do nothing to help in finding the number. Four of the clues are necessary for finding it.

Can you find out, in your group, the four clues that help and the four clues that do not help in finding the number I am thinking of? What is it that you need to know to find a chosen number from your hundred square?

Part 2: What is the number?

This part is to test the students’ conjectures about what they found out in part 1 of the activity.

- Say to the students: ‘I am thinking of a number – in your groups, decide on four clues to ask me to find out what number I am thinking of.’

- After a few minutes ask one group for their clues and try them out. Whether they work or not, ask for the reason they chose those four clues. Ask if a group has a different set of clues and try those out. Stop when the clues work and discover your chosen number.

- Repeat this for several different numbers, or ask a student to take over your role and think of a number.

- Follow this with a discussion of which four clues are not needed to find the number, and why this is. What makes the best clues, and why?

(Source: adapted from NRICH, http://nrich.maths.org/ 5950 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .)

Video: Using local resources |

Case Study 1: Mrs Bhatia reflects on using Activity 1

This is the account of a teacher who tried Activity 1 with her elementary students

I do agree that games are fun activities to do but I am always a bit sceptical when it is claimed they can offer rich opportunities for learning mathematics. I found it hard to believe that these number games could supplement the learning that happens in the normal traditional teaching I do in my classroom, when I explain mathematical ideas clearly to my students. But I decided to give it a go because I do find that even my younger students seem bored at times when doing mathematics, and that saddens me and makes me feel I have to try something else.

My class is large – about 80 students. Although they are supposed to be only from Classes III and IV, the attainment between the students varies a lot: some of the students seem to still struggle with early-year concepts of numbers, others are happy and able to do the work of higher classes. Finding activities that all of them can do and that challenge them all is very hard.

As I do not have access to resources such as a photocopier or large sheets of paper or scales for all students, in preparation for this activity I asked the students to draw a hundred square on the inside cover of their exercise books for homework. Most of the students had already done this, but some had not. I did not want to spend any time in the lesson letting those students draw one there and then so I made sure that when the students went into groups of four or five they were sat right next to someone who had done the homework so they could both look at the same hundred square. To move them into groups I simply asked the odd rows of students to turn around and work with the students sitting opposite them.

I was very uncomfortable with not giving the students precise instructions on how to go about finding out which clues were necessary or not, or to discuss this with the whole class first. I was really worried they would not know what to do. But I thought I would try and see if the activity would work and presented the task in the way it was described.

I decided that if the students still did not know how to proceed after four minutes, I would tell them. It did not take them that long. To make sure they were on-task I walked through the classroom and listened in on their discussions. I asked some of the groups ‘How will you find out?’ Their answers varied in the choice of numbers they would try the clues with, and their rationale for why to pick those. I noticed that neighbouring groups would listen to their replies as well, sometimes changing their approaches. In that way they all learned from each other without having to stop the whole class to discuss this.

I really liked the buzz in the class – there was excitement and engagement. The students were smiling a lot and developing their mathematical arguments to discuss, agree and disagree with each other. Everyone seemed to have a point to make and seemed to be included in the work of the groups.

After a while I told them they had three more minutes to decide on the clues, and that they had to make sure that everyone in their group knew and understood what the agreed clues were. I asked that because I wanted to make sure that all students in the group, whatever their attainment, would learn from this game. For this reason I also did not ask the ‘smartest’ student of the group the questions in the second part of the activity.

The discussion about why the clues were needed or not needed gave the students the opportunity to talk about their ideas. Sometimes, at the first go, they expressed themselves clumsily, but I then asked them to ‘say that again’, and I was amazed by how quickly most of them managed to express themselves more fluently the second time round. To make sure that not only the ‘smartest’ students answered I asked any student whether they agreed with what was said and insisted on them repeating the statement in their own words if they did. If they did not agree, they had to say why.

Reflecting on your teaching practice

When you do such an exercise with your class, reflect afterwards on what went well and what went less well. Consider the questions that led to the students being interested and being able to progress, and those you needed to clarify. Such reflection always helps with finding a ‘script’ that helps you engage the students to find mathematics interesting and enjoyable. If they do not understand and cannot do something, they are less likely to become involved. Do this reflective exercise every time you undertake the activities, noting, as Mrs Bhatia did some of the smaller things that made a difference.

Pause for thought Good questions to trigger reflection are:

|

What you can learn in this unit