1 Generating ideas for writing

Writing in another language is difficult. When students write in English, they have to think about things like grammar and vocabulary, using the correct punctuation, and spelling. When writing at school, your students are probably worried about making mistakes and getting low grades. Of course, these are important, but there is more to writing than these aspects.

When you write something, you want to communicate something to your reader. The reader might be yourself (for example, if you have written some notes on something you have read, or if you have written a shopping list), or somebody else (your headteacher reading an application that you have written is one example). In composing the text, you might have considered how best to organise your messages. You might even have written more than one draft or asked somebody to check your work – especially if the text is about something important or will be made public.

Effective writers think about the language that they are using but they also think about what they want to say and the potential reader or readers of what they write. They think about how to organise their points logically so that what they have written is clear – and, hopefully, interesting. They review their work and perhaps write more than one draft; they may also ask others to review their work before writing a final draft.

You can help your students to develop the skills of effective writing. This will help them to write better English compositions that have the ideas logically organised, are interesting to read and are more accurate. These skills will also be useful for writing in other languages. The process of organising ideas, reviewing work and writing drafts will make them more effective writers in general.

One of the problems that a writer in any language has is knowing what to say. This can be particularly difficult when writing in English. Sometimes the topics in the textbook are difficult; sometimes students don’t have the language they need to write about these topics.

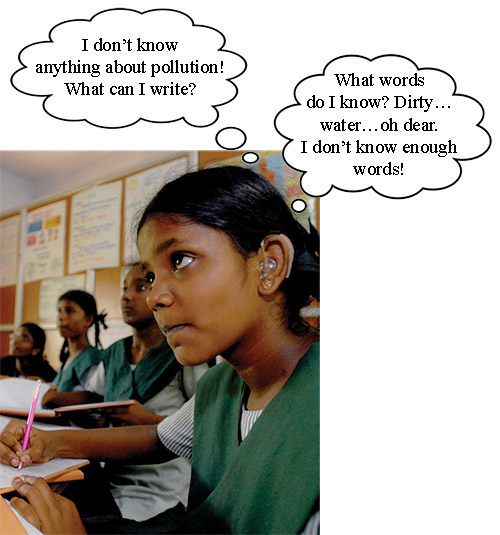

Pause for thought Imagine that your students have to write a composition with the title ‘Pollution’. What problems do you think they might have? |

Read what this student is thinking:

With a topic such as pollution, students may not know much about it – and even if they do, they may not have the language skills to be able to write about it in English. This means that they may struggle to write more than one or two lines.

Pause for thought Think about these questions and, if possible, discuss them with a colleague:

|

One technique that you could use to generate ideas and language is brainstorming. This involves giving students a prompt – for example, the word ‘pollution’ written on the blackboard, or pictures from a newspaper of a polluted river or city – and then collecting ideas from your students relating to the word or picture. You can write the students’ ideas on the blackboard, or your class can work in groups, with one student noting down all the ideas in their notebooks or on chart paper. Encourage students to use their imagination and to suggest as many words and ideas as they can.

Once your students have contributed their ideas, they need to discuss and decide which ideas to keep. You can do this with the whole class, or if students are working in groups, the group members can do this together.

Brainstorming is a helpful technique to use in the classroom because it:

- generates ideas for content so that students will know what to write (or speak) about

- generates key words and phrases that they can use when they write (or speak)

- helps students who need more support

- helps you to see what your students remember from previous lessons and what they already know

- encourages students to share and learn from each other

- develops creativity

- encourages less confident students to contribute ideas without them being exposed to one-to-one questioning where the whole class is waiting for their response.

See Resource 1, ‘Talk for learning’, for more on brainstorming and value of getting students talking.

Case Study 1: Mrs Bhatia tries a brainstorming session in her English class

Mrs Bhatia teaches English to Class IX. The Hindi teacher at her school told her about brainstorming, and Mrs Bhatia tried it with her students.

I decided to try a brainstorming session with the writing task in the chapter we were studying. [Chapter 8 of the NCERT Class IX textbook Beehive – see Resource 2 for the complete text.] The writing task had the following instructions:

Working in pairs, go through the table below that gives you information about the top women tennis players since 1975. Write a short article for your school magazine comparing and contrasting the players in terms of their duration at the top. Mention some qualities that you think may be responsible for their brief or long stay at the top spot.

Once my students had read the instructions, I asked them a few questions to generate some ideas about the qualities of a successful tennis player, and some language for the writing task.

I told my students they could speak in their home languages if they needed to, and as they gave suggestions for words and expressions, I wrote them in English on the board. Some students made suggestions in English, and they often made mistakes; for example, one student said ‘shorter as’ instead of ‘shorter than’. I didn’t correct him, though – I just said it correctly in English and wrote the correct version on the board. The most important thing was to get ideas, and if I corrected everyone when they spoke, they would feel discouraged.

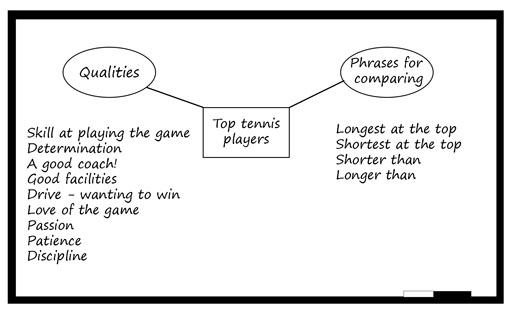

As I wrote words and phrases on the board, I read them out so that students could hear the pronunciation of any new vocabulary, and I checked that students understood the meanings. I also organised the words and ideas into different sub-topics such as ‘qualities’ and ‘phrases for comparing’ as I wrote. Sometimes, students made suggestions that were not very useful. Kalika suggested ‘nervous’ as a quality. I wrote it on the board anyway. Once all of the ideas were on the board, we discussed them and decided to reject a few of the words and phrases (including the word ‘nervous’).

At the end of the brainstorming session, this is what my board looked like:

I organised my students into pairs, and asked them to do the writing task. I know that some teachers worry about students doing writing activities in pairs – they feel that the weaker students may simply copy from the stronger ones. I find this can sometimes happen, but when students work in pairs they are able to generate even more ideas, and are able to discuss how to use the language written on the board. In this way, everyone benefits.

When the class finished, I took in some of my students’ written work to look over. I was happy to see that the students had written more than usual, and that they used the new language well.

I will try this again the next time there is a writing task in the textbook. Next time, however, I will ask my students to brainstorm their ideas in groups first. This will encourage more students to contribute to the activity.

Activity 1: Try in the classroom – using brainstorming for a writing task

You can use brainstorming with any class, and with many different writing tasks from the textbook. Follow these steps to try it with your students:

- Before the lesson begins, choose a writing task from your textbook or a topic that your students have to write about in exams (such as ‘My favourite festival’ or ‘My favourite leader’).

- Imagine that you have to write this composition. Which words and phrases are useful? Write them down. Write down the questions that you will ask your students around the topic to help them generate ideas. This prepares you for the lesson.

- In class, write the topic title in the centre of the blackboard (such as ‘My favourite leader’), or tell your students to read the instructions for the writing task in their textbooks.

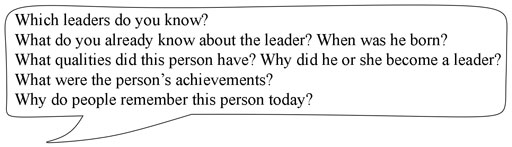

- Ask some questions to generate ideas about the topic. Encourage different students to contribute ideas. If your students are finding it difficult to think of ideas in English, let them use another language and then ask other students to translate. As they generate ideas, write them on the board. If they struggle, you might ask some prompt questions – but only as a last resort, because brainstorming is about valuing and capturing students’ ideas. Some example questions for ‘My favourite leader’ are:

- When students have finished suggesting ideas, you should have a lot of words on the board. At this stage, discuss how students might organise their ideas. Which words and phrases belong together? Which ideas might come first?

- Tell your students to write about the topic, and set a time limit. They could work individually or in pairs.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

It can be difficult for students to contribute at first, and you may find that one or two students dominate. If this is the case, you can put students into groups and give them some time (for example, five minutes) to discuss ideas, words and phrases.

An alternative to using the brainstorming technique is to announce the topic a week or two in advance so that everyone has the chance to think about and research it. Then when you ask for ideas from the class, most students will be able to contribute.

What you can learn in this unit