Resource 3: An introduction to action research in the classroom

Ben Goldacre (2013) argues that teaching should be an evidence-based profession and that this would lead to better outcomes for children. In particular, he suggests that a change in culture is needed, in which teachers and politicians recognise that we don’t necessarily ‘know’ what works best – we need evidence that something works.

The assumption is that the evidence-based practice is a good thing and that the changes advocated by Goldacre can be achieved through teachers researching their own practice. Indeed, where research practices are embedded in schools, there is a recognition that this can contribute to school improvement.

As a teacher undertaking a study in your own classroom, it is likely that it will be relatively small-scale and short-term and action research methodology works well in this context. Action research involves practitioners systematically investigating their own practice, with a view to improving it.

Action research involves the following steps:

- Identify a problem that you want to solve in your classroom: This might be something quite specific such as why certain pupils do not answer questions or find an aspect of your subject hard or de-motivating, or it might be something more general like how to organise group work effectively.

- Define the purpose and clarify what form the intervention might take: This will involve consulting the literature and finding out what is already known about this issue.

- Plan an intervention designed to tackle the issue.

- Collect empirical data and analyse it.

- Plan another intervention: This will be based on what you find and will be designed to further understand the issue that you have identified.

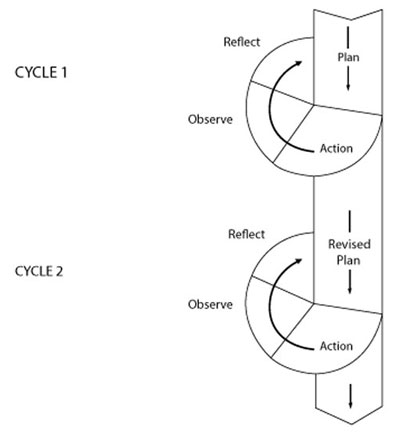

Action research is a cyclical process (Figure R3.1). Through repeated intervention and analysis, you will come to understand the issue or problem and hopefully to do something about it.

Figure R3.1 Action research cycle

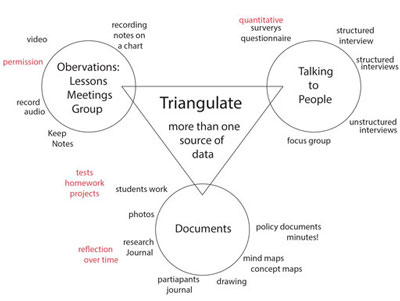

Having decided on the questions you would like to answer and the approach you wish take, you will need to collect some data that will enable you to answer the questions. There are three broad ways in which you can collect data, you can:

- observe people at work

- ask questions (either through survey’s or by talking to people)

- analyse documents.

Figure R3.2 provides an overview of different data collection methods.

You will need evidence from several sources of data in order to be confident in your findings. Each method will have advantages and limitations; you need to make sure that you act in such a way as to minimise the limitations.

You need to consider both the validity and reliability of the data that you collect. If something is valid then that suggests that it is true or trustworthy. It is useful to ask the following questions to test validity:

- Can the results be generalised? Someone who hears about or reads about your research might decide that, based on their experience then it is authentic and seems sensible.

- Does the data support the conclusions? This is more likely if there is more than one source of data collected over a period of time or if the findings have been checked with the participants.

- Do the questionnaire or interview questions relate clearly to the research questions?

Reliability is a difficult concept as it is to do with repeatability and replicability. Reliability includes fidelity to real life, authenticity and meaningfulness to the respondents. Cohen et al. (2003) suggest that the notion of reliability should be construed as ‘dependability’ and achieving dependability relies on factors such as collecting enough data, checking your findings with the participants, and looking for evidence of the same idea from more than one data source.

Resource 2: Storytelling, songs, role play and drama