1 What coaching and mentoring have in common

Most people speak of coaching and mentoring as if they were the same thing. While they are two different approaches to working with individuals and teams, they do have one important thing in common: both depend for their effectiveness on being able to develop strong, trusting relationships with the person who the coach or mentor is helping. Learning how to hold consensual conversations is really important in forming such relationships.

A consensual conversation is one in which the two speakers are in harmony. While the purpose of their conversation may not be to seek agreement, they do agree about how they will:

- listen to and understand each other

- show true interest in what the other person is sharing

- show respect for the other person and for the views that they express.

As a school leader, you may be used to having people agree with you just because of who you are. Holding truly consensual conversations may therefore be a skill that you often have to learn and practise!

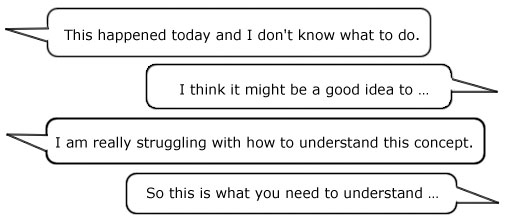

Figure 1 A conversation with a clear purpose.

It is important to remember that two colleagues casually talking with each other about their work is simply a ‘chat’. When their conversation is deliberately designed to help one of them address a problem or seize an opportunity, it has a clear purpose – ultimately, to improve teaching and learning – and moves into the territory of coaching or mentoring.

Activity 1: What sets coaching and mentoring apart?

Read the definitions of coaching and mentoring in Resource 1. Write down in your Learning Diary your own summary of the difference between the two terms, thinking about how you might explain the concepts to your staff.

List three ways in which coaching and/or mentoring could make a difference to staff performance and therefore student learning in your school. You might, for example, think about specific staff or about specific student needs or about a curriculum area that you are concerned about.

Discussion

It is important to distinguish the role of mentor and coach, as they operate in different ways and offer different types of support. When you differentiated between the two and thought about ways you might use these approaches in you school, you probably realised that it is important to pick the right approach and that they are both about an ongoing commitment to developing your staff, not about single conversations. What drives coaching and mentoring is the goal of improving teaching and learning, and conversations should focus on this.

- A mentor is usually an experienced specialist in their chosen field and, ideally, is also a wise person who has a wide range of experiences to draw upon. They bring to you their considerable experience and knowledge of the subject to be discussed.

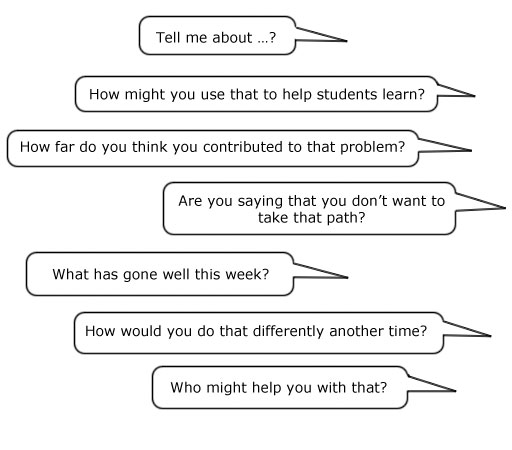

- A coach helps you to come up with your own answers to issues that you are struggling with. Their most common tool is the question, and their most valued characteristic is the quality of their listening.

Did you think of ways that coaching or mentoring might help in your school? Maybe you have in mind a new teacher who would benefit from a weekly session of mentoring to guide them to put their training into practice in the classroom, advising on how to deal with issues and manage their class. You may have thought about the issue of low participation of female students in classes and thought how you could use coaching to encourage teachers to improve participation in learning. You might want to see an improvement in science teaching and ask a senior science teacher to mentor their colleagues to pass on their expertise.

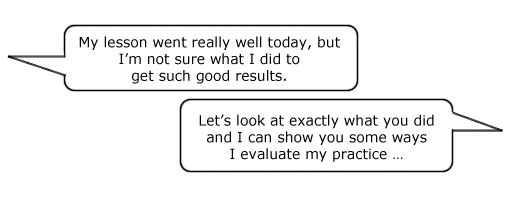

Most of us have benefited at some time from the support of a mentor in our personal or professional lives. In almost every family there is a wise ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’ who is consulted before any life-changing decision is taken. As a school leader, you will certainly have to undertake this role, whether it is supporting a colleague through a crisis or helping them improve their classroom practice. Typically, the mentor will come up with answers to questions and solutions to problems. The best of them have the ability to ask really good questions that help their mentee come up with their own answers. However, the mentor has in mind what the answer might be. Over time they act as guides on a road that they have already travelled. A mentoring conversation might go like this:

The job of a coach is to draw out the thoughts, ideas and concerns of the coachee (the person that they are coaching). They do this first to help them decide what exactly they want to talk about and can then replay what is said in order to help the coachee ‘hear’ their own thoughts and ideas. The coach’s persistent refusal to contribute their own ideas is essential for the coachee to come up with their own solutions. The most common habit is to sit still and say nothing; this may be the biggest challenge of all for you in learning to coach. A coach’s questions might be:

It is important to remember that coaching and mentoring conversations should celebrate the skills and successes, not just any deficits. Teachers need to recognise what they do well in order to repeat and develop it, and coaching and mentoring should identify strengths as well as weaknesses.

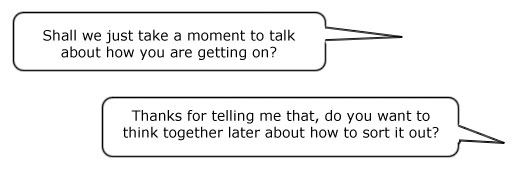

At times, mentoring and coaching conversations may touch on personal issues. It is important to remember, however, that your purpose is to help the individual solve a professional problem with a view to improving their performance and student learning.

Activity 2: Who do I need to listen to?

In this activity you should think about the sorts of challenges that you and your colleagues face in school that would benefit from a mentoring or coaching conversation. Work on the first part of the activity alone. You might wish to encourage others to offer their ideas for the second part.

Reflect on the following prompts and jot down your thoughts in your Learning Diary:

- Focus on two teachers in your school. One should be less experienced who you might mentor so that they can benefit from your knowledge and skills. The other teacher might be someone who you think could benefit from rethinking their approach or finding solutions to some of the problems that they are encountering.

- Identify the sort of issues or incidents that have arisen for them in the last week that have impacted on their teaching. This could be very varied, such as non-attendance due to the harvest, low confidence in teaching an unfamiliar subject, late students regularly disrupting the lesson or having to teach two classes due to shortage of teachers.

Now you have identified a ‘who’ and ‘about what’, copy Table 1 below into your Learning Diary and fill in the first two columns.

| Colleague role | Issue, incident or opportunity | Type of conversation: coaching or mentoring | Venue | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

||||

|

Now decide if the approach you should take is mentoring or coaching, and write this in the next column against each colleague you have identified. Think about whether you are helping people find their own solutions through questioning and listening (coaching) or whether you are taking more of an expert role and guiding them as to what to do using your expertise (mentoring). You may find that you also use coaching with the inexperienced teacher (for example, to help them to generate ideas for engaging with parents) and on some issues – such as taking responsibility for the maths curriculum across the school – you decide to mentor the other teacher over a period of time. The two approaches are not exclusive.

Use the fourth column to think about where you will have this conversation; the venue. Mentoring someone on developing their teaching resources and displays would probably take place in a classroom, while coaching someone to improve their marking of student work will need to be somewhere where neither of you will be disturbed. Remember that conversations can take place in a classroom or a quiet corner of the school grounds. Your office, if you have one, is probably the worst place to try to talk to someone, because of the power issues associated with that environment. The subject of the conversation will often determine the venue.

Lastly, make some notes in the final column to remind you of any issues and to guide your conversation.

Discussion

Now look at Table 2, which shows an example of a matrix filled out by a school leader when they were planning two conversations in their week. How does it compare to yours?

Table 2 Colleague coaching and mentoring matrix – filled-in example.

| Colleague role | Issue, incident or opportunity | Type of conversation: coaching or mentoring | Venue | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Family illness | Mentoring | Anywhere where they can have a cup of tea and not feel uncomfortable | You will want to be as supportive as possible to the member of staff but you are primarily concerned with minimising the impact on student learning. |

| Subject head | How to deal with an under-performing member of staff in their department | Coaching/mentoring | In their office or classroom, as long as you will not be disturbed | Although it may be necessary to provide some guidance, the aim is to help the head of department to come up with the solution to a problem they have been avoiding all year. This conversation is not about the under-performance as such; it is about developing the skills and confidence in the subject head to tackle the issue. |

It is helpful to think ahead to make your conversations most effective. This way you can ensure that you broach difficulties with tact but directness, as you will have thought ahead about what to say and where to say it. Often the opportunity to have these conversations presents itself as part of a daily routine, and this is another reason to be ready to talk with your colleagues naturally and in a spontaneous fashion – for example:

What school leaders can learn in this unit