2 Some theories behind change, planning and implementing change in school

There are three theories of change that are relevant to the work of school leaders. These theories are not recipes for change, but provide a way of thinking about change. The leader cannot change what has happened in the past but has considerable scope to influence how individuals respond to change in the future, and their commitment to it.

Theory 1: Change as a series of steps

Knoster et al. (2000) saw five dimensions of change (Figure 2).

Knoster et al.’s work showed that if any one of these dimensions was missing, the change was likely to be unsuccessful. This has been captured in Table 1. A tick (![]() ) indicates a dimension that is in place; a cross (✗) shows where a dimension is missing. For example, where there is no vision (as in the first row), there will be an outcome of confusion because the reason for change and the intended outcome is unclear.

) indicates a dimension that is in place; a cross (✗) shows where a dimension is missing. For example, where there is no vision (as in the first row), there will be an outcome of confusion because the reason for change and the intended outcome is unclear.

| Vision | Resources | Skills | Incentives | Action planning | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | Confusion | ||||

| ✗ | Frustration | ||||

| ✗ | Anxiety | ||||

| ✗ | Complacency | ||||

| ✗ | Gradual change | ||||

| Effective change |

One word of caution surrounds resources. Resources include human and material resources. Many changes in school can be made within existing material resources or through relatively minor additions. The most significant resource in most educational change is the human resource. A poor teacher in a high-tech classroom is still a poor teacher. A good teacher with few resources is still a good teacher.

Case Study 1: Mrs Gupta wants a change in teaching

Mrs Gupta is school leader of a mixed secondary school in an urban area where there is a wide range of students.

I visited a nearby school that was getting good results and saw teachers using a variety of teaching methods that involved the students actively in lessons. There was groupwork and independent work, and the teachers used many questioning techniques to get students to think about what they were learning. More able students often helped those who had difficulty recording work on their own, and the teachers had made a variety of materials such as flashcards and pictures to make their lessons more interesting. Much of this, along with student work, was displayed on the walls.

Back at my school, I decided that we need to make some changes to the teaching in our school. I called a staff meeting and I told my staff what I had seen and how good the school was. I explained that I wanted students to be more actively involved in their learning and that I wanted everyone to plan a lesson next week using groupwork. I would be visiting them in classes to see how they were progressing.

Activity 2: What did Mrs Gupta miss out?

Refer to Table 1 and then note the answers to these questions in your Learning Diary:

- What elements of the change process did Mrs Gupta miss out?

- How effective is her attempt to bring about change likely to be?

- What else does she need to do?

Discussion

Mrs Gupta had a vision that she explained to the teachers in her school. However, it is not clear that they understood or agreed with her vision. She made a plan and she introduced an incentive – that she would be visiting their classroom. For the teachers, that probably felt more like a threat. Teachers need to be motivated, and this is a key leadership responsibility. Effective incentives (rather than threats) are about recognition, receiving praise and being part of a successful team.

She didn’t provide any resources to support the teachers, or check that they had the necessary skills. If she had talked to the school leader from the other school, she might have gained advice and evidence to help her articulate her vision to her staff. Also, she might have been given some tips about the resources and skills that were developed.

Resources were not needed to start work on the project, although they would help in many ways. For example, Mrs Gupta could have offered to take some classes so that teachers could visit the nearby school and see for themselves the sorts of things that she wanted them to do.

Mrs Gupta made a plan but it was unrealistic because she expected instant change rather than a planned approach in which staff could try out ideas in a developmental manner.

Case Study 2: Mr Chadha leads a new approach to assessment

Primary headteacher Mr Chadha attended a course on embedding continuous and comprehensive evaluation (CCE) in his school.

The course explained all the reasons for CCE and gave some really convincing examples that showed how CCE can improve learning. I went back to school feeling really inspired. In the next staff meeting I explained CCE to my staff (I have six teachers working in my school) and said that in the next few weeks they would all have the opportunity to attend a course at the DIET [District Institute of Educational Training]. They could see how enthusiastic I was and welcomed the opportunity to learn more. I also explained that I would be asking the SMC [school management committee] if I could reorganise the budget to buy some resources for their classrooms to support CCE.

They came back from the course with plenty of ideas and a detailed training manual. For the first two weeks, there was plenty going on. When I was walking around the school, I could hear teachers asking more questions, giving encouraging feedback and checking understanding. But then there was a week’s holiday and when we came back, it was as if everything had been forgotten. The training manuals remained on the shelf and the teachers were teaching in the way that they always had. I did not know what to do.

I decided to investigate. I spoke to the two teachers who had been the most enthusiastic about the course. They agreed that CCE sounded good in theory, but that it was hard to do – it was taking longer to plan lessons and they were worried about finishing the syllabus. One was finding it difficult because he had 60 students in his class.

I realised that this was too much change too soon. The teachers had quickly forgotten the course and that one course was not sufficient for them to develop the skills required. I needed a new plan.

I invited the trainer to come to school to talk to all of us in a staff meeting and to give some practical examples for CCE in action. I then divided the teachers into groups of three. The idea was that they would mentor and coach each other. I asked each teacher to focus on CCE for one week, with the other two acting as mentors. So at the end of three weeks, everyone had had the opportunity to try out new techniques. Each day, one group of three missed assembly and used the time to discuss their plans for CCE and receive feedback. I also encouraged them to visit each other’s lessons, and I offered to teach their classes so they could do so.

This worked much better. After three weeks, everyone had had the opportunity to focus on CCE with the support of two colleagues. The mentoring process had also been helpful. Everyone decided to carry on the work for another three weeks, with each teacher concentrating on CCE for one week and supporting others for two weeks.

Case Study 2 demonstrates that even if all the elements of change are present (vision, resources, skills, incentives and action planning), then the change might not be successful. In this case, developing the skills required was more difficult than Mr Chadha expected – teachers needed ongoing support and encouragement rather than a single training course.

Theory 2: Change formula

No theory of change is a perfect description of how change happens, but it can help a leader to think about change in their context. Gleicher’s change formula (quoted in Beckhard, 1975) is another theory that can be helpful when embarking on the change process. The formula charts the necessary qualities that the change needs to contain if it is to become embedded in your school.

The formula is:

D × V × F > R

It is explained as follows:

- ‘D’ is the need for change already being registered by people’s dissatisfaction with the reality today.

- ‘V’ is the vision for change being sufficiently compelling that most people are able to visualise what is possible.

- ‘F’ represents the first steps towards implementing the change being valued by the whole community.

- If the previous three are in place, then it is likely that together their impact will be greater than the inevitable and understandable resistance (‘R’) that there will be to the change.

The challenge for a school leader is to persuade teachers that they are ‘dissatisfied’ with the thing that you want to change. Your teachers are likely to be ‘dissatisfied’ by a number of things, such as a lack of resources, the size of their class, the amount of work they are expected to get through or the number of students completing their homework on time. They are less likely to be ‘dissatisfied’ with the amount of participatory learning taking place in their classroom, or the amount of CCE that they are doing.

There are a number of things that you can do to motivate your teachers and persuade them to make the sorts of changes that you desire. Here are two examples from school leaders in India:

- The teachers in Mr Aparajeeta’s school were always rushing to complete the syllabus. He had noticed, however, that the exam results were consistently poor. Even though the teachers were covering the whole of the syllabus, only half of the students could achieve the 40 per cent grade that was required to pass. Mr Aparajeeta decided that it would be much better for them to teach key concepts properly so that students really understood them, rather than to cover every detail in the textbook. After all, the students all have the textbook and if they understand the work they are more likely to be motivated to read it for themselves. He therefore told his teachers that they did not have to stick rigidly to the textbook. They could introduce a new topic however they wanted, as long as it engaged the students, and they had to pick out the activities that related to the key concepts rather than try and do every activity. He encouraged them to work in departmental groups to identify the key concepts and created time for subject group meetings by not holding any staff meetings for a term.

- Mrs Kapur was frustrated because her teachers would not complete the marking sheets for tests and exams so she could not do a proper analysis of how each year group was progressing. They marked the tests and handed them back, but then said they did not have time to keep records. She said that they would need the record sheets for the parent’s meeting, but some of the teachers pointed out that hardly anyone came to these meetings. Mrs Kapur went to the local village to talk to some of the parents. She listened as they told her about their farm and how busy they were. She used an analogy to explain why they should come to the parents’ evening. She pointed out that when they had planted their seeds, they didn’t just leave them in the field. They checked regularly to make sure that they had enough water, that there were no pests and that the plants were thriving. They needed to do the same for their children. She explained that their child was like a seed and that they should take the opportunity to check that they are learning and thriving at school. At the next parents’ evening, the attendance was much better. Some of the teachers were embarrassed because they were not able to show the parents detailed records of their child’s progress. The record-keeping in the school soon began to improve and Mrs Kapur was able to analyse progress more effectively.

In the first example, Mr Aparajeeta tackles an issue that his teachers are already dissatisfied about. In the second example, Mrs Kapur has to employ a certain amount of cunning in order to create the circumstances in which the teachers realise for themselves that they need to keep records of student progress. Other strategies that you could use include the following:

- Making it clear that the change is coming from the government and that you are all going to work together to make it work.

- Involving teachers in the school review process (see the leadership unit on school self-review) so that they have first-hand knowledge about how the school is performing.

- Encouraging teachers to take responsibility for issues in their class. This could be attendance, the proportion of students completing their homework, appearance, punctuality or the smartest classroom. You could do this by instigating a weekly award for the class which performs the best in your chosen category.

Pause for thought

|

Theory 3: Force field analysis

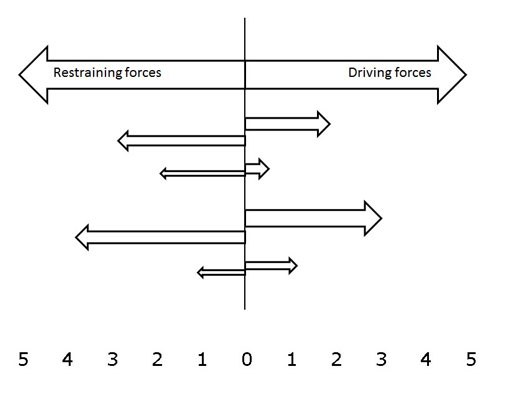

Another theory of change is ‘force field analysis’. This approach to change encourages you to focus on the conditions that are already in place that will firstly support the change and secondly identify the likely sources of resistance.

How to do a force field analysis:

- State clearly the change that is wanted.

- Draw a vertical line from the statement of change down a large piece of paper (or on a board or computer screen).

- Draw the driving forces on the right-hand side of the line and the restraining forces on the left.

- For each force the length of the arrow (from 0–5) reflects the extent of the factor, with 5 being the most powerful.

- The thickness of each arrow represents the relative importance of the force.

In the following case study, Mr Agarwal uses force field analysis to help plan a change in the approach to homework in his secondary school (although it could be used in a primary school as well).

Case Study 3: Mr Agarwal tackles homework

During my learning walks last term, and conversations with teachers in the staffroom, I noticed that there was a great deal of dissatisfaction with the homework that students were doing. It was often rushed, untidy, incomplete or simply not done. Teachers felt frustrated because students were missing out on the opportunity to consolidate the work, and they felt as if they were continually nagging rather than building positive relationships with their students.

I held a staff meeting at the beginning of term and explained that I wanted us to tackle this issue together. I quoted things that I had seen and things people had said, and very soon there was an animated discussion about the poor level of homework. I held the meeting in a classroom so that we could use the blackboard to do a force field analysis.

The change that we wanted to bring about was to improve the quality of homework done by students. We tried to think about all the things that could help us with this and the things that might make it difficult.

This is what we came up with as driving forces:

- Parents are keen for their children to be set homework.

- A carefully planned homework exercise can support learning.

- Setting homework helps us to finish the syllabus.

- The NCF 2005 expects us to set homework.

- All schools set homework, so we could go and talk to colleagues from another school to see how they tackle this issue.

- The SMC expects students to be set homework on a regular basis.

And here are the restraining forces we identified:

- Some students are expected to do household chores in the evening and have no time to do homework.

- It is difficult to think of suitable homework exercises, so we often resort to copying notes from the textbook, which must be a bit boring for the students.

- Planning lessons takes a long time – planning homework as well is really difficult.

- Homework creates a huge amount of marking (‘I have 60 students in my class and I cannot possibly mark their homework, so it feels like a waste of time’).

- Students just copy each other’s homework, which is a waste of time.

- The observation that it is impossible to check everyone’s homework, which for some of the students is an excuse for not doing it.

Activity 3: Using force field analysis in your school

Look at the list of driving forces and restraining forces that Mr Agarwal and his teachers made in Case Study 3. Now try to put these into the same format as Figure 4, with the longest arrows for the most powerful issues (for example, the SMC monitoring homework) and the fattest arrows for the most important (such as teachers setting appropriate homework). Put the most important factors at the top of your figure. Using Mr Agarwal’s list gives you a chance to practise this method.

As you draw a figure in your Learning Diary, consider whether there is anything that you would add to the list from your own context and what you could do in order to harness the driving forces and reduce the restraining forces.

Discussion

By first listing and categorising the issues, and then giving them weight, you can prioritise your efforts to tackle the restraining forces and make the most of the driving forces. It is easy to lose sight of what is important and what drives change. Such graphic representations can help you to organise your findings and share them with others. Read Case Study 4 to see what Mr Agarwal did in order to bring about change.

Case Study 4: Mr Agarwal identifies the forces at play

After we made our lists, we decided that the biggest driving force was the opportunity that homework gives for finishing the syllabus. We may set the task of reading some of the textbook, but many teachers admitted that they never check that the work has been understood. One of the smallest driving forces was the support from the parents. This was because we live in an area where many parents have not been educated themselves and cannot see the point. (I also noted privately that one of the biggest driving forces was Ms Nagaraju, a teacher who seemed to be very enthusiastic about the whole exercise and determined to improve homework in her class.)

The biggest restraining force seemed to be the expectation of students to do chores, or paid work in the evenings. (Although, privately, I noted that the extra planning involved in setting good quality homework exercises that support learning was clearly a problem, and Mr Meganathan, who has been teaching for 20 years, was very negative.)

Change theories

Each of the change theories described provides a slightly different perspective and stresses slightly different things. However, they share several characteristics. Change is affected by:

- individuals’ responses to the current situation

- the understanding of what the change will look like (visualisation)

- motivation to make the change

- previous experiences

- the means to carry out the change – resources and skills

- planning.

Activity 4: Why do changes fail?

You will have experienced many changes in your role as a teacher and school leader. Think of a change or initiative that was less than successful. Maybe it failed to enthuse people, or was poorly timed or just too ambitious. It may have been a change that you organised, or perhaps it was organised by someone else. Use the theories described above to identify why it failed.

If you were involved in the change again, what could be done differently? Try and identify something from each of the theories that would make a difference. You may find it useful to share your ideas with another school leader, as discussion can bring out other interpretations and perspectives.

Discussion

The change might have failed because one of the steps in theory 1 was not completed, or was underestimated. It might be that there was insufficient dissatisfaction with the present (theory 2), the vision was not clear enough or the first steps were too ambitious. It is possible that the people leading the change did not take account of the factors that could help them or would restrain them (theory 3).

Alternatively, despite all the careful planning, it is possible that the change was just too ambitious for one person working alone. Change is often more effective when a team is leading it.

1 The change context