2 Teaching community-based approaches

The science involved in social and environmental issues is often complicated. But don’t worry – you don’t need to be an expert. Your role is to help your students understand how to use their science knowledge to make responsible decisions in their own lives.

Also, it is important to remember that there are often no ‘right’ answers to some of the issues that you will raise. For example, ‘Which sort of power station should be built?’, ‘Should we support the development of genetically modified (GM) crops?’ and ‘Should we spend money on exploring the other planets in the solar system?’ All of these involve people developing convincing arguments to persuade others.

In science lessons you are preparing your students to be informed citizens and helping them to understand the underlying scientific principles. It is an opportunity for them to develop a wide range of skills.

Pause for thought

|

Informed citizens are able to process information, assess the validity of an argument, and take a critical approach to evidence. They are prepared to listen to different points of view. They respect the opinions of others and they are able to articulate their own view and support it with evidence. The teaching approaches described in the next section will help your students to develop these skills.

Group discussions

Small group discussions can result in high levels of participation. Group talk is important because it helps students to learn to reason. Learning to reason requires the ability to use the ideas and language of science to begin to construct arguments that link evidence and data to ideas and theories. Effective small group discussion requires students to justify the reasons for their beliefs.

But you need to plan effective group discussion. You need to be very clear about what you want students to discuss and what the outcome of their work is going to be. You will need to provide them with some prompts to get them going, and give them a sense of purpose.

Pause for thought

|

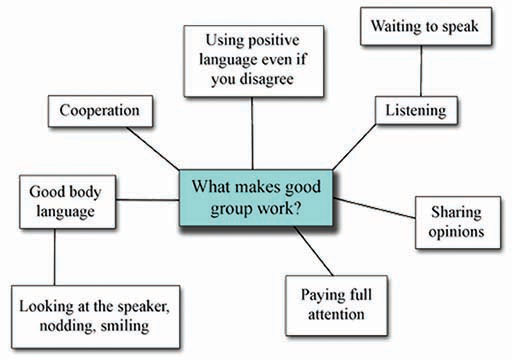

Have a look at Resource 1 on groupwork and compare your thoughts with the ideas given there. In order to have a successful group discussion, your students will need:

- some specific questions to discuss

- some background information on the topic

- a clear goal or purpose for the discussion.

Your students will need practice at working effectively in a group; they need to learn the skills required. Look at Resource 1 for more information on groupwork.

Case Study 2: Social issues linked to river pollution

Mrs Verma wanted her students to be capable of dealing responsibly with social issues, specifically those that could be better understood with the help of science. She decided teach water pollution to her Class IX, by focusing on using social issues to initiate a classroom discussion. Read her account of her approach.

I asked my students to sit in their usual groups of four to six, and they quickly got themselves organised. They were sitting with people they had worked with in other science lessons. I chose these groups because I wanted them to have the confidence to say what they thought and bring out the issues.

Before writing the topic on the blackboard, I asked the students, ‘Can we go and drink water directly from Yamuna river in our city?’ Since news of the deteriorating condition of the Yamuna river water was a burning issue, most of the students replied in chorus, ‘No, it’s polluted.’ This confirmed to me how aware my students were and that we could proceed to discuss water pollution that day.

I provided each group with some pictures of people using the river for different activities. The pictures were downloaded from the internet but I did wonder if I might have hand-drawn them instead, especially as I did not find all the pictures I wanted.

I then wrote a key question on the blackboard: ‘How do these activities affect our water resources?’ I asked the students to note down whatever they discussed in their groups so that they could contribute these ideas to class discussion at a later stage.

I have found that with a large class, there are invariably very diverse viewpoints that are always interesting. The classroom was quite noisy as the groups discussed their pictures, and I moved around the groups to check that they did not become unruly. After giving them ten minutes I asked them to stop their discussions.

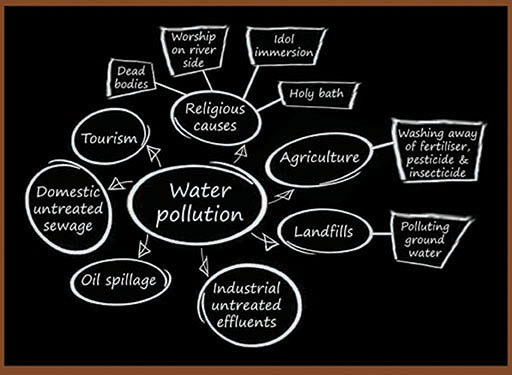

I then asked each group in turn to give me one idea and pointed from one group to another until there were no new ideas. This took another ten minutes. The students suggested many things that could have affected the river, such as: dead bodies being in the water, where they decay and contaminate it; untreated sewage of daily activities from whole cities flowing into it; pollution from chemicals; and, every year, thousands of idol immersions contaminating the water.

As they called out their ideas, I praised the groups and wrote them on the blackboard to show how concepts are grouped and connected [Figure 2]. Deciding where to put the ideas sometimes generated a discussion itself, such as whether pouring some old engine oil into the river was industrial effluent or domestic waste.

Once we had completed the representation of the various causes of water pollution, I moved the discussion on to focus on some more specific issues. I gave each group a piece of paper with one of the following statements and asked them to debate what was written on it:

- A river cannot purify itself where there is a high density of people, due to the large number of rituals that are performed. So the rituals should be limited.

- Religious beliefs are an integral part of our lives, but clean drinking water is a greater necessity of life.

- A single person’s actions have a cumulative impact on a whole society, and therefore on the entire ecology of the planet, so we should each act to stop pollution.

- Pollution comes about because of ignorance of long-term consequences, so education is the solution.

- A farmer can increase his yield by 50 per cent with chemical fertilisers, so any harm to the environment is less important.

- Industry provides jobs and prosperity. The fact that factories may pollute the river is less important than that.

I then asked them to vote within their group on whether they agreed with the statement or not. I stressed that it was OK to disagree, and that they should listen to one another’s views. Again there was a lot of loud discussion in the groups. I was particularly pleased to notice that Anju, who is not usually interested in science, had a great deal to say about the effect of religious ceremonies on the pollution in the river.

I clapped my hands when it was time to vote, and each group voted on their issue. They then read their statement out to the rest of the class and let us know what the voting results were, as well as the arguments for and against each statement.

It was good to hear my students continuing their discussions at the end of the lesson, as they left the room. I was pleased that they were so engaged with the topic and able to consider the science behind it.

I decided that some other time I would provide them with some scientific data (for example, about deaths from water-borne diseases, numbers of rituals per annum, annual volume of a single human’s waste, incidence of birth defects) to help their discussions.

Pause for thought Re-read the paragraph before the case study and reflect on the things that Mrs Verma did to ensure that the discussion was productive. |

Mrs Verma provided some background information in the form of some pictures of activities that affected the river. She gave her students a relatively easy thing to discuss first before moving on to the more specific and controversial questions. By the end of the lesson, the students should have had a good overview of the causes of water pollution and have realised that people need to take responsibility for their actions. Hopefully, some of them will be beginning to appreciate the challenge of how to control people’s behaviour and the importance of government structures in doing so.

1 Making links between environmental and social issues and the curriculum